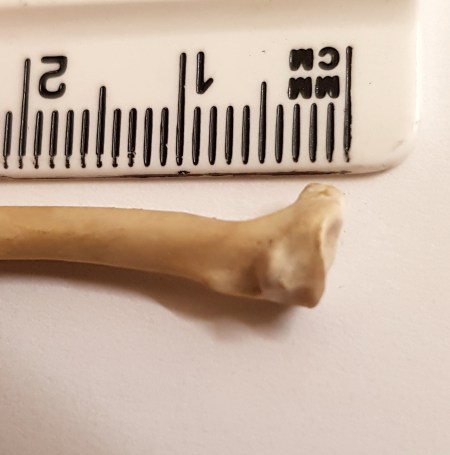

Last week I gave you the challenge of identifying this bit of bone found in a rockpool in Kimmeridge by 7 year old Annie:

It’s not the easiest item to identify for a variety of reasons. First of all it’s broken, only showing one end and probably missing quite a lot of the element. Next, the images don’t show all of the angles you might want to see and because the object is small the images aren’t as clear as you might like.

However, there are a few angles visible (see below) and there is a scale, so the main requirements to get an approximate identification are in place. I say approximate, because with something like this I think you really need the object in your hand where you can compare it to other material in detail if you want to make a confident identification.

Excuses aside, let’s take a look and see what it might be…

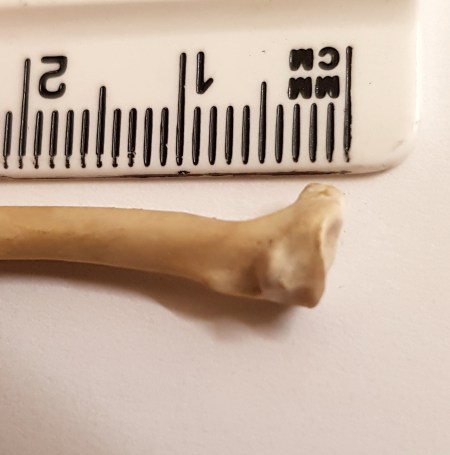

The first thing to note is that the bone is hollow with thin walls. This rules out fish, reptiles, amphibians and mammals (including humans jennifermacaire) – leaving birds.

Weathered mammal bones may have a void in the bone where the marrow would have been, but the cortex (outside layer) will be thicker and near the articular surface it tends to be quite solid.

Hollow bone = bird (usually)

Next, the articular surface of the bone is concave, which palfreyman1414 picked up on:

As far as I recall (mentally running through images in my head) both ends of the proximal limb bones in tetrapods have convex ends?

This is accurate, but while the proximal (near end) of the limb bones are convex, the more distal (far end) limb bones tend to have concave ends, so that helps narrow down what this bony element might be.

Concave articulation

For me the give-away here is the fact that there’s no ridge within the concavity of the articular surface, which means that it will allow movement in several directions – something that the bones of bird feet don’t really need, which is why bird lower legs, feet and toes have a raised ridge inside the articular surface that corresponds with a groove in the other surface, keeping the articulation of the joint tightly constrained.

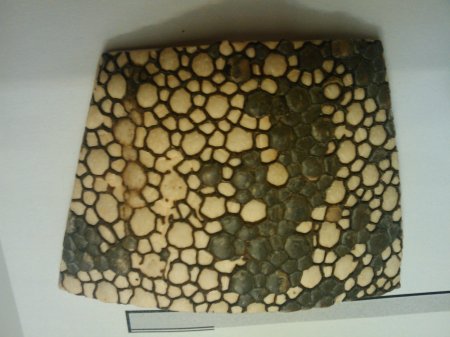

Articulation of Shag phalanx showing raised ridge

However, bird wing need to make a wider range of motion (at least in some species), so the mystery object is most likely the distal end of a bird radius (the ulna tends to have a hook at the distal end). This is the conclusion that Wouter van Gestel and DrewM also came to (joe vans should’ve stuck to his guns).

Distal articulation if duck radius

Identifying the species of bird is a lot more complicated. The size suggests a pretty big bird, which narrows it down and the locality in which it was found makes some species more likely than others. I took a look at the radius of some species that are commonly found on the coast, like Guillemot, Herring Gull, Duck, Cormorant/Shag and Gannet, Skimmer, Pigeon and I also checked out Chicken, since their bones are probably the most commonly occurring on the planet.

Gannet radius with some distinctive structure around the articulation

Many of the species I checked had quite a distinctive structure around the distal radius articulation, but the gulls, ducks and chickens that I looked at had fairly unremarkable distal radius articulations, making it hard to definitively decide what the mystery object is based on the images.

Herring Gull radius

Chicken radius

So with that somewhat disappointing conclusion I admit partial defeat, but I can say that it’s not from a Cormorant, Shag, Gannet, Pigeon or Guillemot. Sorry I can’t be more specific Annie!

Unfortunately that’s just how the identification game works sometimes… we’ll try again with something new next week!