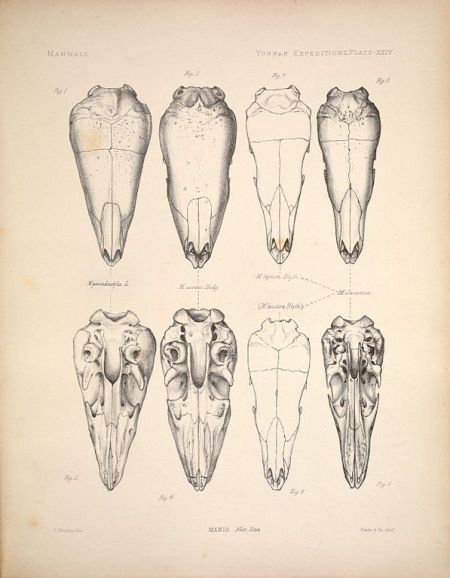

Last week I gave you this ungulate skull to try your hand at identifying:

It isn’t made any easier by the fact that it’s a female, so it lacks the horns or antlers that make identification easier. As with many ungulates it looks a bit sheepy (as I’ve mention before), but it has some clear indicators that helped you rule out what it’s not.

Jake spotted that the size was about right for a Roe Deer, but the auditory bullae (the bulbs on the underside of the skull that house the ear bones) are too massive and the proportions of the braincase are quite different.

Joe vans also ruled out deer, since it lacks lacrimal pits (large openings in front of the eyes that hold scent glands in cervids). Joe also noticed that the mandible is extremely pinched in just behind the incisors.

The incisors themselves caught the attention of Allen Hazen, who noted the extreme size of the first incisor, which he correctly recognised as being a bit of a giveaway to some people, although only when considered in the context of a variety of other features.

While Daniel Calleri summarised these odd features and added the observation of the decent sized occiptial condyl (the place where the atlas vertebra attaches to the skull) and small paracondylar processes (the bony extensions either side of the occipital condyl and just behind the auditory bullae).

These sorts of observations are exactly what are needed to differentiate between species that are very similar in overall morphology. However, without either an excellent reference collection, or even better, a well researched key, it’s almost impossible.

Fortunately, there is a skull key for a subset of Antelope that occur in Tanzania, created by the Field Museum and the mystery object this week happens to be from a genus present in Tanzania. I’d recommend having a go at using the key, but if you’d rather just find out the answer I’ve provided a link to what it is here. Have fun with the key and enjoy your Easter!