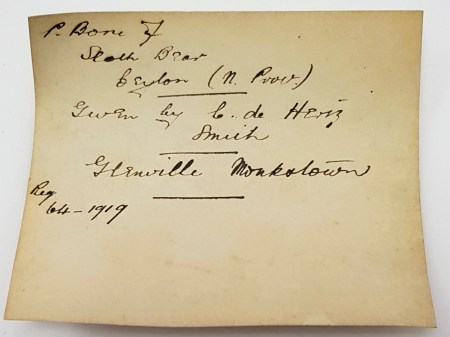

The other Friday I gave you this specimen to have a go at identifying, but alas when the time came to write an answer I was at the Natural Sciences Collections Association (normally just called NatSCA) conference (which has been referred to as “the highlight of the natural history curator’s year”) and as a result I didn’t get much of a chance to write an answer or even read the comments.

Now I’m back, buoyed up by the fantastic shared experience of the conference (take a look at the #NatSCA2018 hashtag to get an idea of what was going on) and I’ve finally have a chance to look at the specimen, read the comments and write an answer. I was delighted to find some great cryptic poetry, prose and comments – some requiring perhaps a little more intellectual prowess than I’m capable of commanding, especially after an intense few days of conferencing (sorry salliereynolds!)

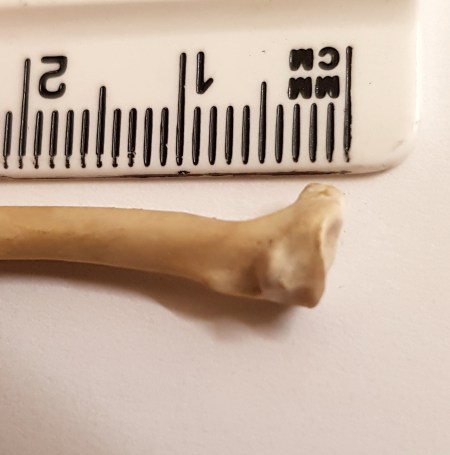

This specimen has a somewhat thrush-like appearance, but the hooked tip of the bill doesn’t quite sit right for a member of the Turdidae (the family of true thrushes). This somewhat raptorial feature of the beak is seen more in birds like the Laniidae (shrikes) and some of the Saxicolinae (chats). It’s the chats that I’m interested in with regard to this specimen, although not the “typical” chats. The ones I’m interested in have been moved around taxonomically a fair bit.

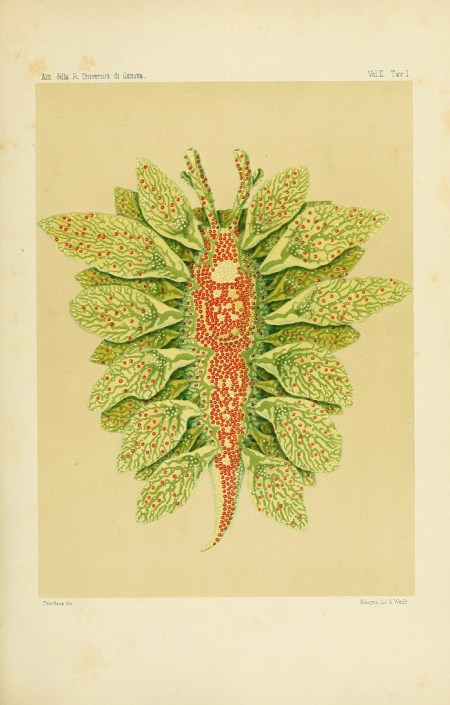

A lot of birds with a thrush-like general appearance will have been called a “something-thrush” by Europeans and will have kept that in their common name even after taxonomy has moved on and that species has been moved out of the Turdidae. In the Saxicolinae there are a lot of birds that were once considered thrushes and one genus in particular tends towards being a fairly dark colour with blue elements – Myophonus or the whistling-thrushes.

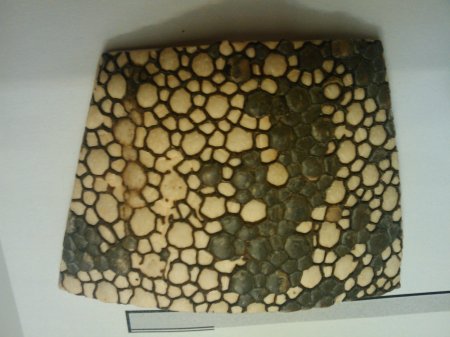

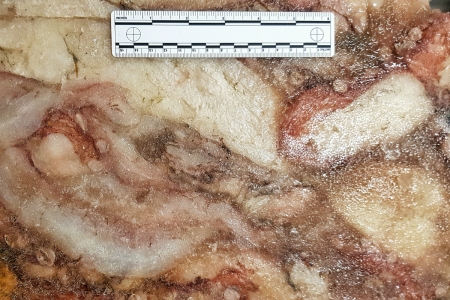

The distribution of glossy blue feathers on members of Myophonus is variable and reasonably distinctive. Also, because these glossy feather colours are structural, they don’t tend to fade in old museum specimens like the colour from pigments. In this specimen the blue patch is fairly dull and confined to the shoulder (or epaulet) and the rest of the plumage is even more dull – possibly faded, but also possibly because it’s female (we all know that it’s usually the boys that are show-offs).

Keeping in mind the distinctive bill, overall size and pattern of colouration, a trawl through the epic Del Hoyo, et al. Handbook of the Birds of the World -Volume 10 yielded one description that fit rather well – that of the female Javan Whistling-thrush Myophonus glaucinus (Temminck, 1823).

These forest dwelling birds live in, you guessed it, Java. They feed on various invertebrates and frogs, a slightly ramped-up diet from thrushes, necessitating a hooked bill tip to keep the more jumpy morsels from getting away.

More mysteries to come this Friday!