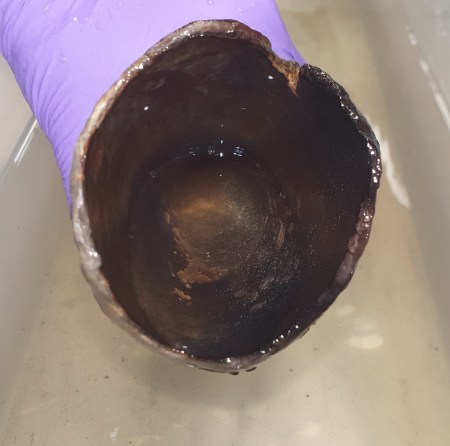

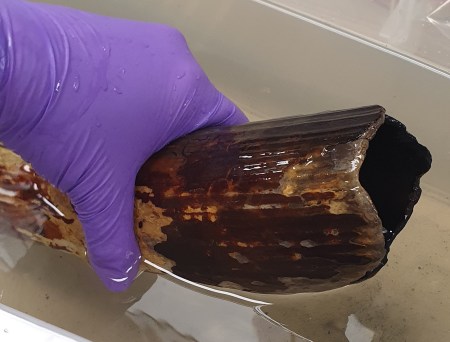

Last week I gave you a close-up of an object that caught my attention when visiting a friend who works at the Natural History Museum, Denmark:

The original image I had gave a bit too much information to make this a challenge, so I have to admit to doing some judicious cropping, and I wasn’t sure if this was going to be an easy or difficult one,

It turns out I made just difficult enough for most people to get in wrong, but there was one correct answer, from Katenockles on Mastodon:

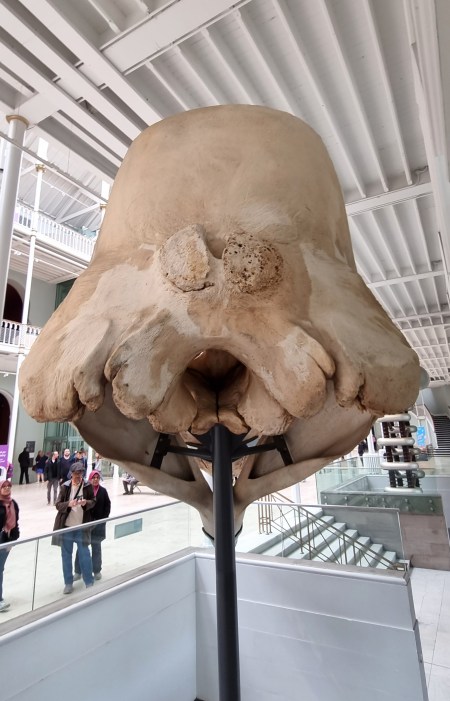

Here’s my original photo:

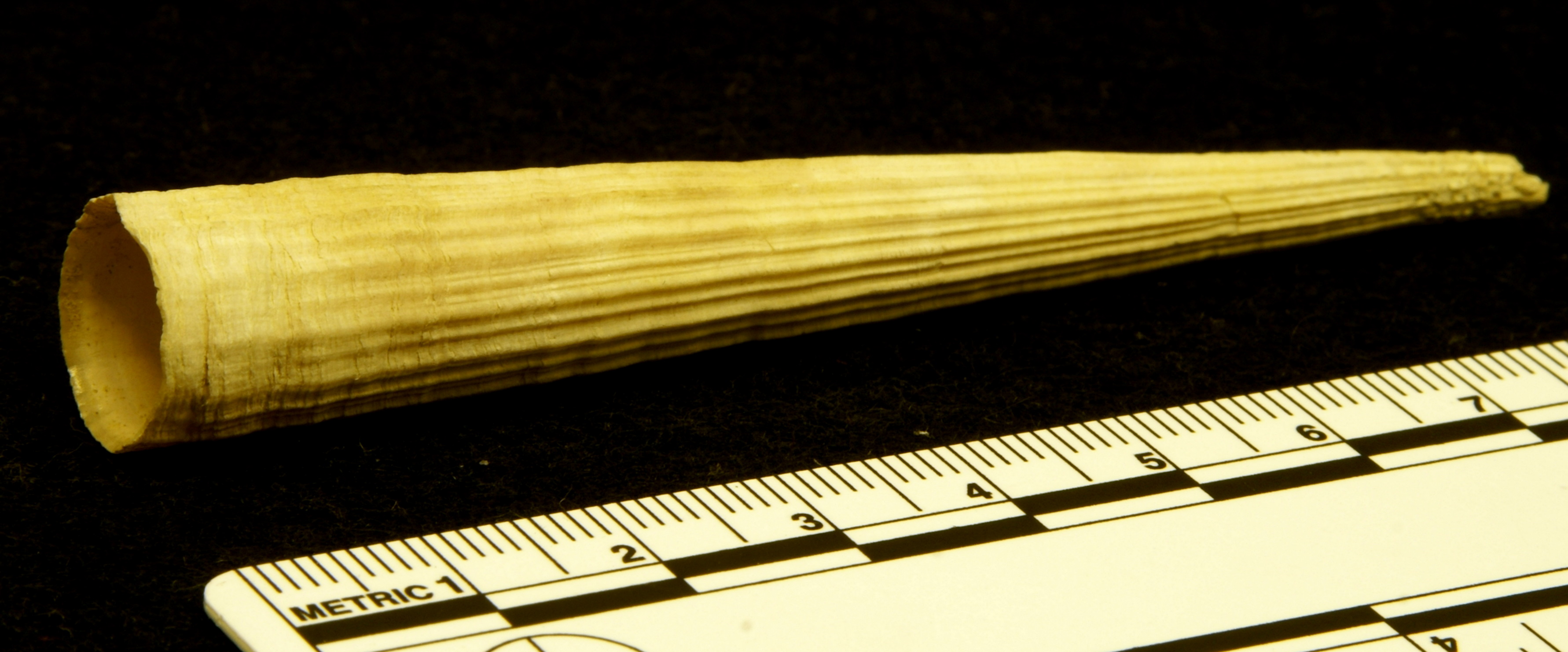

As you can see, this is part of the antler of a Reindeer Rangifer tarandus (Linnaeus, 1758) that still bears the velvet, which is the hairy outer layer of skin covering various layers of tissue. These include the perichondrium and periosteum, which surround and protect the cartilage and bone being grown by highly vascularised mesenchyme tissue and specialised cells such as chondrocytes and osteoblasts. These cells create a scaffold of cartilage that becomes mineralised to form the bone that makes up the antler.

This mechanism for antler growth is really impressive, since it allows these strong and sometimes very large bony structures to develop in around 6 months – sometimes growing over 7cm a week when good nutrition is available.

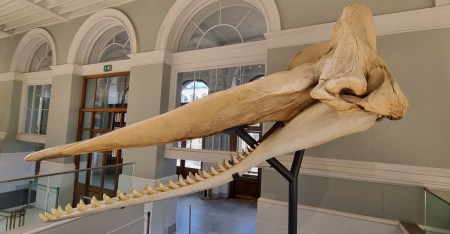

This specimen was of particular interest for me, as I’ve never had the opportunity to see an example of the velvet up close. Normally my interactions with antlers involve historic museum specimens taken as trophies during the hunting season, or fossil examples – like this impressive specimen from the Pleistocene of Ireland:

Thanks to everyone for their suggestions – I can certainly see why kangaroos and camels were suggested, and I’m a bit surprised that nobody suggested Platypus, as that was my immediate thought. Finally, very well done to Katenockles for working it out!