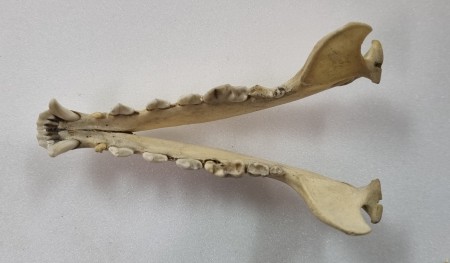

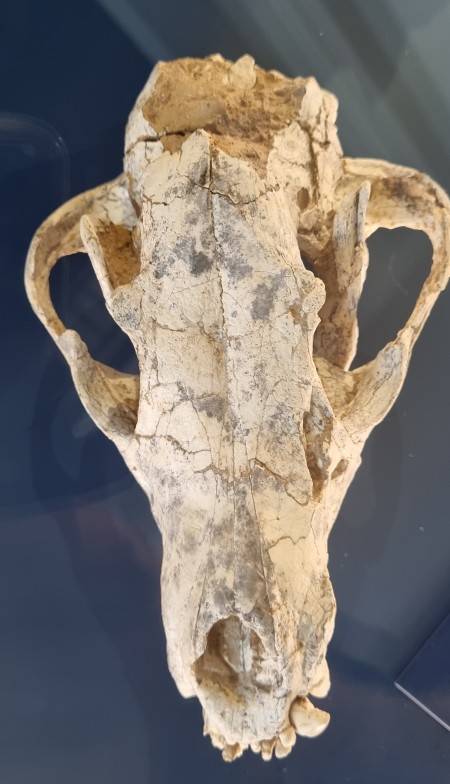

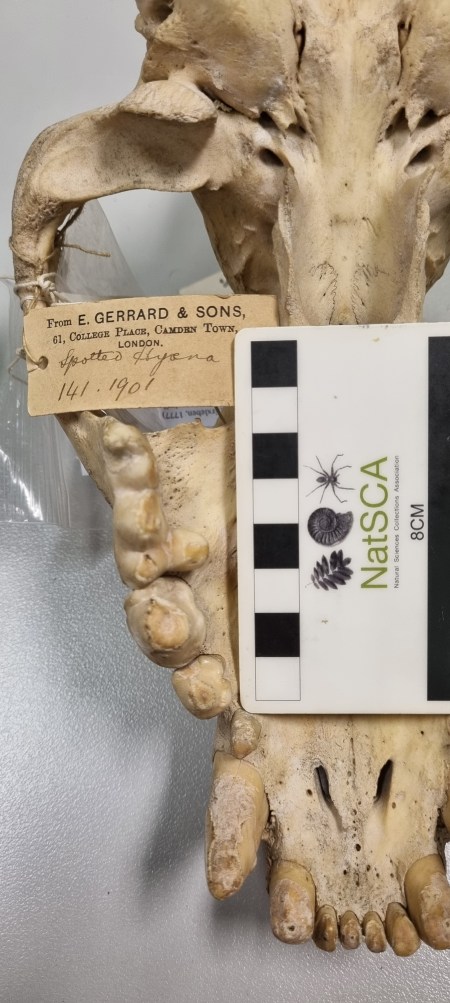

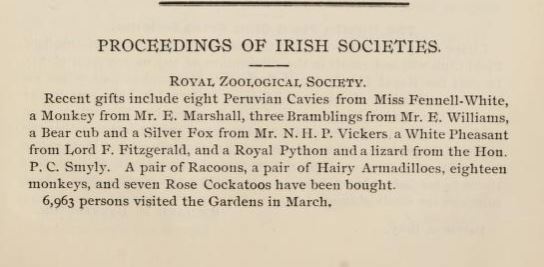

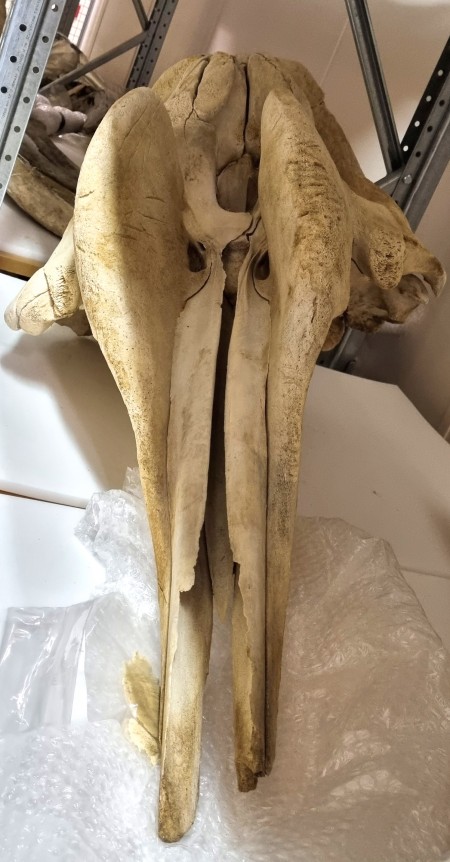

Last week I gave you this neat little skull to have a go at identifying, from research collections of the Dead Zoo in Dublin:

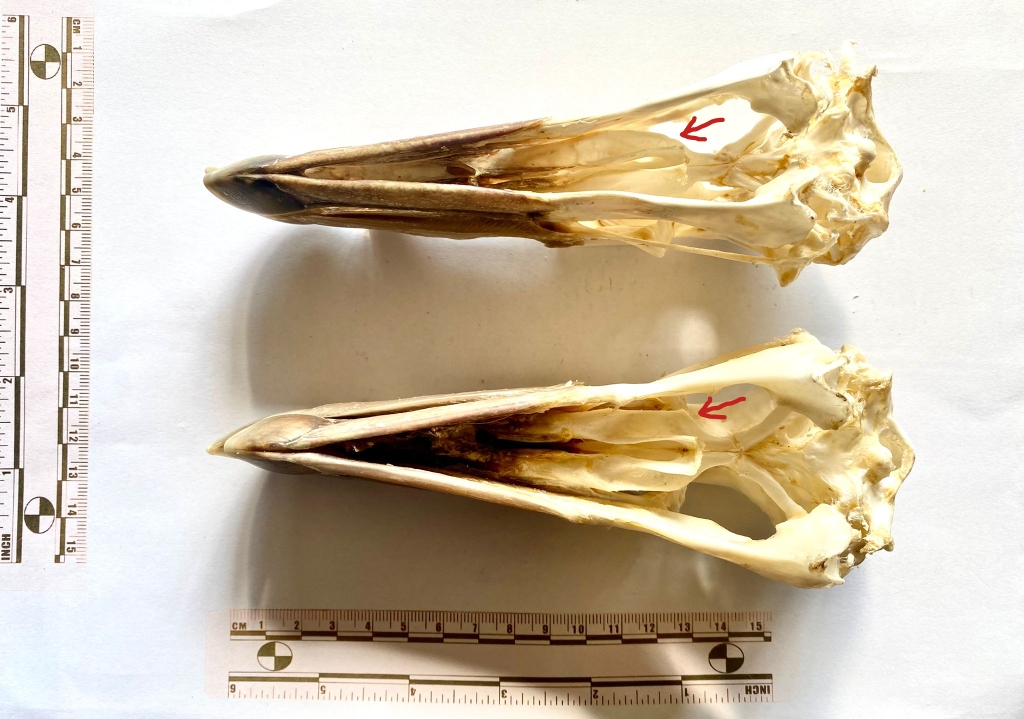

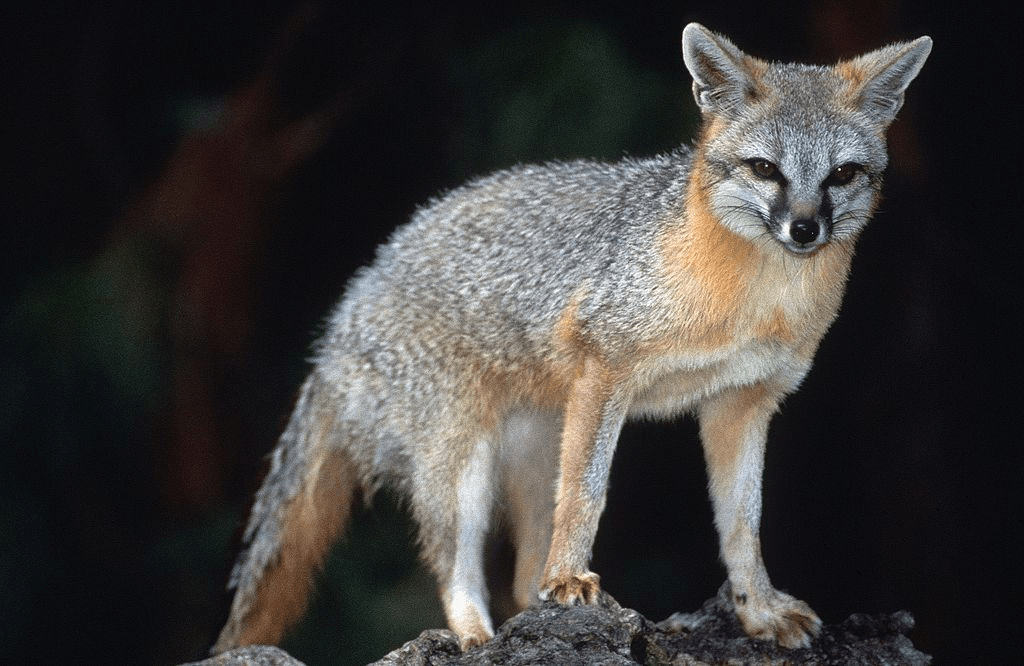

I wasn’t surprised that everyone in the comments worked out that this is the skull of some sort of fox, but I was equally unsurprised that nobody worked out the species. Generally speaking, most people immediately think of the near ubiquitous Red Fox or perhaps Grey Fox (or Gray Fox to our American friends), but there are plenty of others – 24 species commonly referred to as “fox” and 12 species of “true fox” in the genus Vulpes.

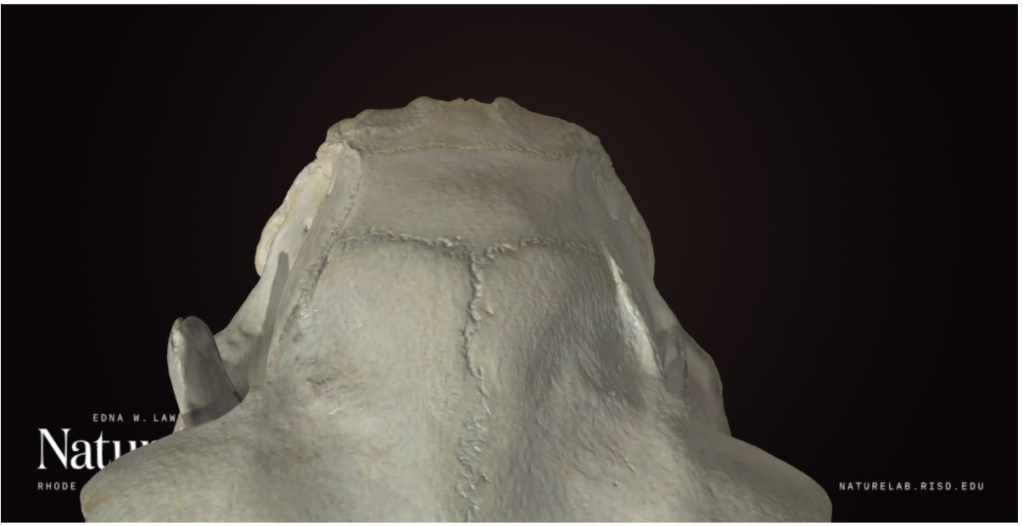

This particular specimen has a sagittal crest that forms a lyre-shape – normally something associated with the Grey Fox:

However, this feature can occur in other species, often in females or subadults, where the surface of the bone has not finished remodelling at the margin of the attachment of the temporalis muscles (those are the ones that connect to the lower jaw from the sides of the cranium and are responsible for the operation of the lower jaw during powerful biting).

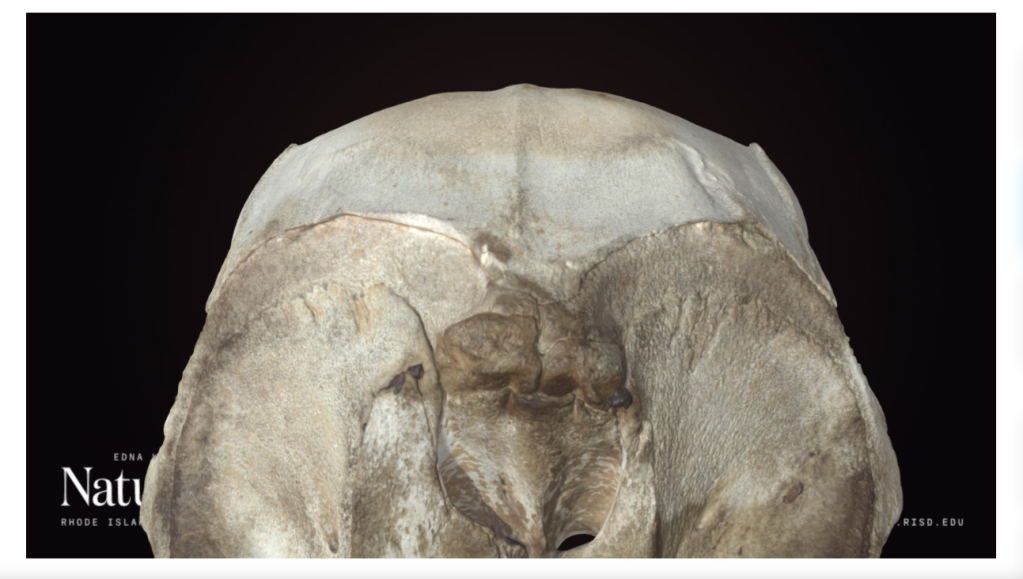

However, in this specimen the muzzle is more tapered and the postorbital constriction is relatively broad. All of these point away from the Grey Fox.

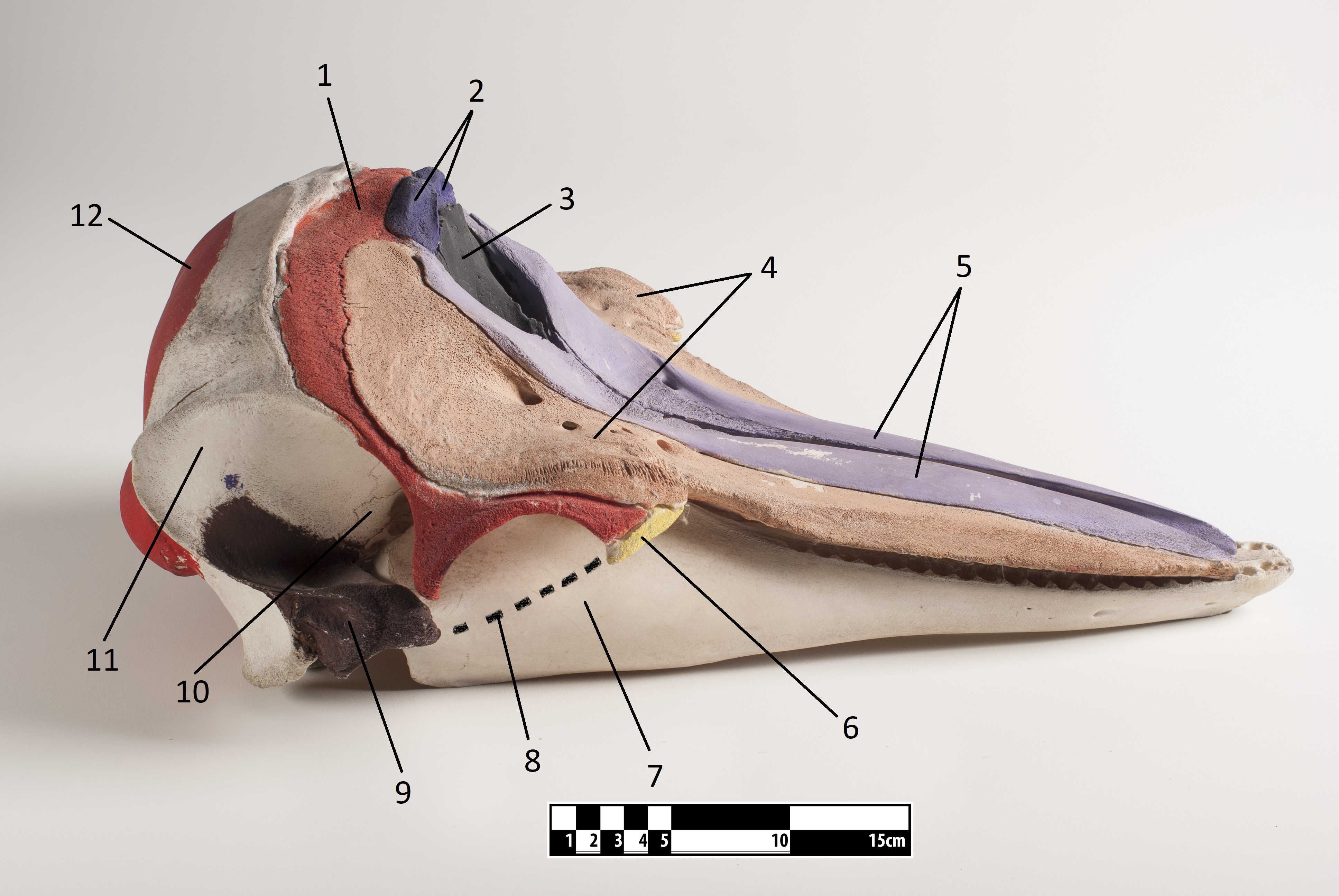

With foxes there can be a lot of similarities between the skulls of species, with all the usual compounding issues of sexual dimorphism, age and regional variation. However, size can give some clues, and things like the relative size of the external auditory meatus (also known as the ear-hole), and the shape of the auditory bulla, are useful for differentiating between species.

With a bit of patience, a bit of pattern recognition, and a resource with good images of specimens, like the Animal Diversity Web, it is possible to work out what you’re looking at.

In this case, the mystery object is a Swift Fox Vulpes velox (Say, 1823).

These North American foxes are smaller than the Red or Grey Fox, but a bit bigger than their close cousin, the Kit Fox. They live in grasslands and praries, where they prey on rodents, birds, reptiles and pretty much anything they can find – including insects, fruit and grasses.

As with many species, the Swift Fox has declined due to changing land use and the systematic persecution of predators in the first half of the 20thC. In fact, it was wiped out in Canada around this time, although it was subsequently successfully reintroduced and numbers have increased.

So watch out for those foxy skulls – there are more species to consider than you might think and they can be tricky to identify without reference resources. I hope you enjoyed this little detour down the fox hole!