Last week I gave you this slightly mean mystery object from the Dead Zoo to have a go at identifying:

I say it’s mean because it’s just a small fragment from the tip of the lower jaw. It does have some pretty distinctive teeth in it, so it’s probably not the most difficult mystery object I’ve shared, but it’s also from a species in a group of animals that are quite poorly known.

That said, Chris Jarvis was the first to comment and got it right immediately. However, there was a lot of subsequent discussion about how to be sure, given the poor representation of comparative specimens available and the similarities between this species and others in the family. That family is the Ziphiidae, which are the the Beaked Whales.

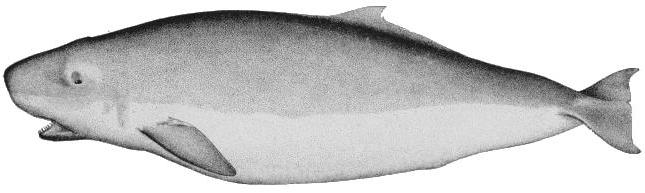

These cetaceans are rarely seen due to their deep water habits, sometimes diving to depths of nearly 3km (although more usually around 1km) to feed mainly on deepwater squid that they detect using echolocation. Most of what’s known about them comes from strandings – which is where this mystery specimen comes from.

The males tend to be smaller than the females, but the males of most of the 21 Beaked Whale species have tusk-like teeth that they probably use to fight over females, although the behaviour hasn’t been recorded, only deduced from scars and the behaviour of other animals with similar sexually dimorphic characters (there’s an interesting paper on the evolution of the tusks by Dalebout et al. 2008 is you’re interested [pdf]).

The teeth occur in different parts of the jaw and have a different shape depending on the species, so the fact these are located at the tip of the lower jaw means quite a lot of the species can be discounted. If you want to be able to do the narrowing down easily I recommend an old and somewhat unwieldy to navigate, but still very useful online resource – the Marine Species Identification Portal. If you can work out the navigation you can find small line drawings of the skulls of all species in lateral view.

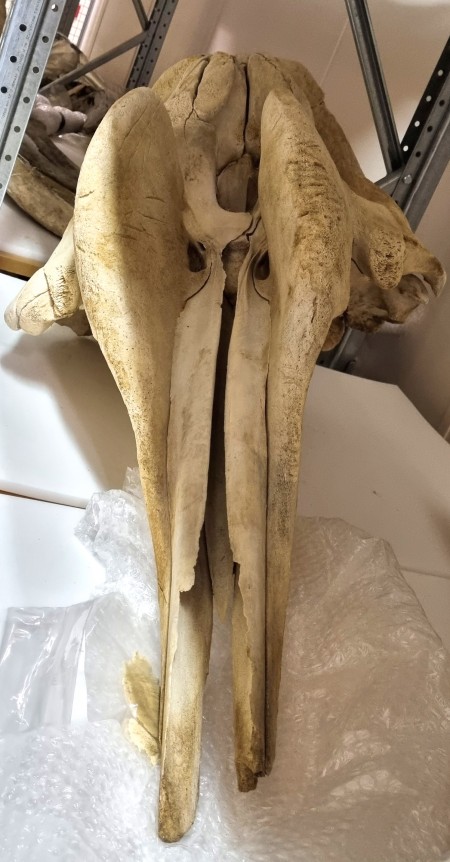

Once you get that far it becomes easier to search for more detailed images of the couple of species it might be, which can yield some great 3D scans to help you work it out. Both Chris Jervis and katedmonson found examples and shared the links in the comments. Here’s a nice one from the NHM, London:

This species (the Cuvier’s Beaked Whale) clearly has bigger tusks than the mystery specimen, which you can see as a scan on the excellent Phenome10K resource*. The mystery object is the distal portion of the mandible of a male True’s Beaked Whale Mesoplodon mirus True, 1913. So well done to Chris Jervis for being the first to get in with the correct identification.

It may seem a bit odd to have just this small portion in the Museum, but as far as records go they represented a managable identifiable voucher for the stranding of the species in Killadoon, Co. Mayo, Ireland back in February 1983. These days we ask for even less material to keep track of strandings – just a small skin sample will do as long as it’s collected and recorded following the guidance of the Irish Whale and Dolphin Group’s (IWDG) Strandings Network.

These samples are stored in alcohol and form the Irish Cetacean Genetic Tissue Bank which is managed in partnership between IWDG and the Dead Zoo to provide genetic data for research into whales. It’s a fantastic resource, but I doubt that anyone could identify the species represented in the samples without access to a genetics lab. And that’s why I like bones best.

*A. Goswami. 2015. Phenome10K: a free online repository for 3-D scans of biological and palaeontological specimens. http://www.phenome10k.org.