Well, it seems that my earlier post on Darwin has ruffled some feathers in the Intelligent Design (ID) camp, so they’ve been trolling the comments section on my personal blog. This post started out as a response, but I decided to expand it to include some of the context surrounding Darwin’s work.

A comment by VMartin

…One wonders why no one noticed “natural selection” before. And there were ingenous minds in the history! One answer might be this – it was never observed because it doesn’t exist. Darwin implanted this speculation there. And “On the origin of species” reads sometimes like comedy. One should try to count how many times Darwin used words like “which seems to me extremely perplexing” etc….

One reason why some scientific theories may have been slow to come to light

It’s interesting how ‘simple’ natural mechanisms and systems can take longer to be acknowledged than one might have thought. Heliocentrism is another example of something that now seems very obvious, but was historically slow to be recognised (and is still not recognised or not known about by some). It’s easy to blame organised religion for the suppression of such observational truths about the universe, since challenges to traditional belief were seen as heresy and dealt with accordingly, but there’s far more to it than that.

Let’s set the scene – Darwin’s formative years were tumultuous with regard to sociopolitical events. The Napoleonic wars drew to an end with the Battle of Waterloo when Darwin was six years old, the Peterloo Massacre occurred and the Six Acts were drawn up by the Tories to suppress radical reformers when he was ten – reflecting the ongoing social division between the establishment and the public. When Darwin was in his twenties the power of the strongly traditional British establishment finally began to wane, when the Whigs came to government allowing the 1832 Reform Act and the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act to be passed. There was also the devastating Great Famine in Ireland when Darwin was in his thirties and all of this was set against a background of the Industrial Revolution, which was providing the impetus for science to play an increasingly important role in society.

Peterloo Massacre

This meant that Darwin’s work was by no means formulated in intellectual isolation. Theories of evolution had been proposed 2,400 years previously, but they were poorly developed. Natural philosophers like Darwin’s own grandfather Erasmus and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck raised the issue of evolution at around the time of Darwin’s birth, but the mechanisms for evolution were either ignored or flawed. Evolution was an established topic of discussion and publication by the time Charles Darwin came onto the scene, with people like Robert Grant being more radical on the subject than Darwin found palatable in his early manhood. Despite this interest, the mechanism of evolution remained elusive – perhaps unsurprisingly, since the academic community addressing natural sciences was largely composed of members of the clergy and the natural theology of the time was seen as being mechanism enough.

But a literature base that was to inspire non-traditional hypotheses was also developing at the time – Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation in particular offered an alternative view that was seen as too radical by many – clearing a path for subsequent works that challenged orthodox views. Given this context, it is perhaps unsurprising that Darwin and Alfred Russell Wallace converged on the same premise at the same time. In short, the ideas evolved to fit the intellectual and social environment. The same has been true of other discoveries and inventions where there was a requirement for the right intellectual groundwork to be laid in advance. This groundwork is required before a robust theory can take root – and Natural Selection is a component of the robust theory of Descent with modification.

The Intelligent Design agenda

The critiques I have seen of evolutionary theory have come from people who quite clearly don’t understand it – and such critiques tend to rely on statements of incredulity rather than a strong factual base. No well-supported alternative hypotheses have been constructed or presented and a lack of understanding hardly counts as a robust refutation of a well supported theory.

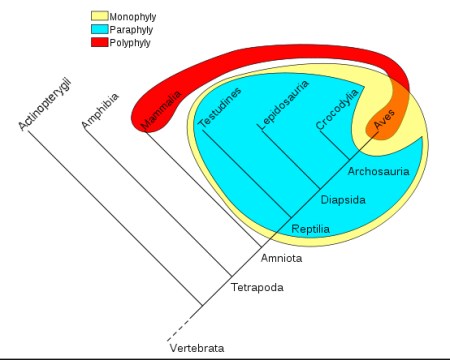

An accusation by IDers is that ‘Darwinists’ (N.B. I don’t know anyone who would call themselves a Darwinists following the New Synthesis) stick with Natural Selection because they are atheist. I think I see the real agenda emerging here, particularly when you see evolution as a theory being conflated with just one of the mechanisms involved. After all, Natural Selection is not the only mechanism involved in evolutionary adaptation and speciation – there are also other factors like hybridisation, horizontal gene transfer, genetic drift, perhaps some epigenetic influences and artefacts of EvoDevo processes. But these factors are still constrained by the simple fact that if they are selected against, they will not be perpetuated.

John A. Davison left this comment on a previous post:

Natural selection is a powerful force in nature. It has but one function which is to prevent change. That is why every chickadee looks like every other chickadee and sounds like every other chickadee – chickadee-dee- dee, chickadee-dee-dee. Sooner or later natural selection has always failed leading to the extinction of nearly all early forms of life. They were replaced by other more prefected forms over the millions of years that creative evolution ws in progress…

Salamander ring species

First and foremost, the suggestion that Natural Selection prevents change is erroneous – change will occur if there is a change in the environment and/or if beneficial mutations arise in a population (tell me that mutations don’t happen – I dare you…). The obvious response to the next statement is that I can think of six different ‘chickadee’ species, with an additional three subspecies (and this is ignoring numerous other very similar members of the Paridae), all are similar, but all are different – so the statement makes no sense as it stands. Getting to the meat of what is being implied about the Creationist interpretation of species, another bird provides a good example to the contrary. The Greenish Warbler shows a distinct pattern of hybridising subspecies across their vast range, until they form reproductively isolated species at the extreme ends of their range, where they happen to overlap yet not hybridise (a classic ring species [pdf of Greenish Warbler paper]). This is a well-known example of how genetic variation can accrue and give rise to new species without any supernatural intercession.

Another comment by VMartin

…But no wonder that Darwin considered “natural selection” for such a complicated force. Even nowadays Dawkins speculates that NS operates on genes, whereas E.O.Wilson has brushed up “group selection” recently (citing of course Darwin as debeatur est .

So may we “uncredulous” ask on which level “natural selection” operates?

As to this question about the level on which Natural Selection operates, I thought the answer was pretty obvious – it operates at every level. Change the focus of Natural Selection from passing on genes to the only alternative outcome – the inability to pass on genes. It doesn’t really matter which level this occurs at or why – be it a reduction in reproductive success when not in a group, or a deleterious single point mutation – if it happens then Natural Selection can be said to have occurred. Being ‘fit’ simply means that an organism has not been selected against.

There’s a lot more to modern evolutionary thought than Darwin’s key early contribution, but Darwin is still respected because he was the first to provide a viable mechanism by which evolution is driven. This mechanism has helped make sense of an awful lot of observations that were previously unaccounted for and, moreover, evolution has been observed and documented on numerous occasions [here’s a pdf summary of some good examples].

I fail to see why Intelligent Design has been taken seriously by some people – it relies on huge assumptions about supernatural interference (so it fails to be a science) and I have as yet never seen a single piece of evidence that actually supports ID claims. The only research I have seen mentioned by proponents of ID are old, cherry-picked studies that report a null result from an evolutionary study – this is not the same thing as support for ID, as anyone who can spot the logical fallacies of false dichotomy and Non sequitur (in particular the fallacy of denying a conjunct) will tell you.

Intelligent design as a scientific idea

I like to keep an open mind, but as soon as I see logical fallacies being wheeled out I lose interest in getting involved in the discussion. This may be a failing on my part, because I should probably challenge misinformation, but quite frankly I don’t have the time or the patience – much as I hate to stoop to an ad hominem, my feelings on this are best summed up by the paraphrase:

when you argue with the ID lot, the best outcome you can hope for is to win an argument with the ID lot

and my time is far too precious to waste arguing with people who ignore the arguments of others and construct Straw man arguments based on cherry-picked and deliberately misrepresented information. I have no problem with other people believing in a god, but please don’t try to bring any god into science (and heaven-forbid the classroom) – since it is neither necessary nor appropriate.