Last week I gave you this mystery object that I found dead in the street when visiting Copenhagen earlier this year:

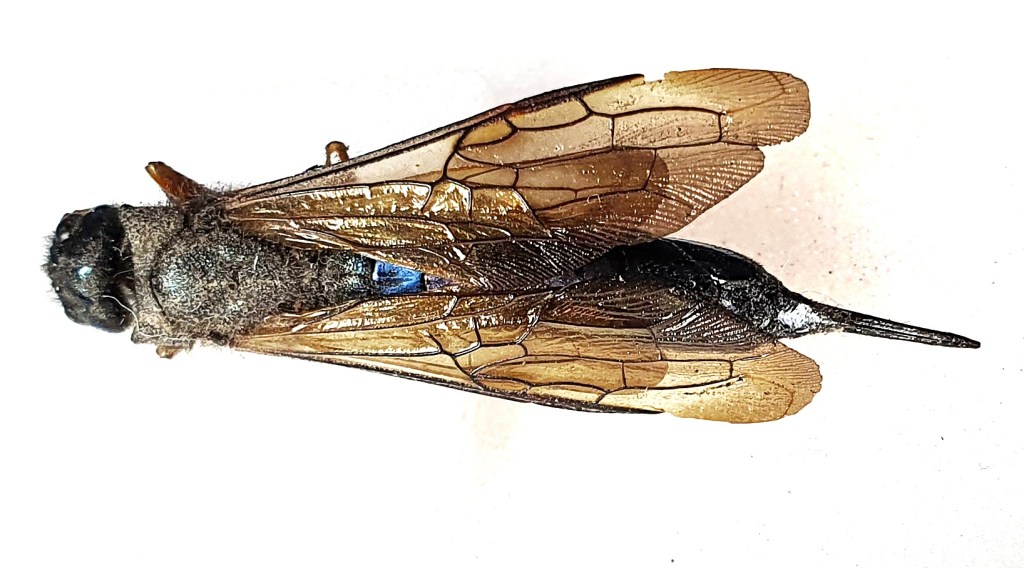

Clearly this is a species of insect in the Order Odonata, which are the dragonflies and damselflies. Damselflies are much slimmer than this, and their wings fold back along their body at rest, so this one is a dragonfly.

Everyone who commented had worked out the species, since the metallic green-bronze body and fuzzy body are quite distinctive.

This is an example of a Downy Emerald Cordulia aenea (Linnaeus, 1758) which is a species that is fairly widespread across northern Europe. While this species does occurs in Ireland, it has only been recorded from a few localities.

We only have one example of this species in the collections of the Dead Zoo, collected in 1978 from County Cork. I was a little surprised that it wasn’t collected by Madame Dragonfly herself, Cynthia Longfield (1896-1991), since she lived in Cork in the 1970s and was a hugely experienced and prolific expert on dragonflies.

Longfield was an adventurous and trailblazing female scientist – the first woman to be a member of the Royal Entomological Society, with expeditions in the 1920s to the Andes, Amazon, Galapagos, Egypt and a host of other localities that she undertook as part of a team from London Zoo, collecting specimens for the Natural History Museum in London, where she later became a voluntary cataloguer and was credited with saving the Museum from fire following bombing during WWII thanks to her actions as part of the Auxillary Fire Service.

Most of Longfield’s collections are held in the NHM, London, but we do have specimens collected by her in the National Museum of Ireland, donated after her retirement and move from South Kensington to Cloyne in County Cork. The Downy Emerald is not one of the specimens we received, but her specimens include new records for Ireland and a number of Paratypes of African species that she collected on her adventures both near and far.