This week I have a fuzzy mystery object for you to identify:

Any idea what this handsome little beast could be? I’m looking forward to hearing your thoughts!

Last week I gave you this fantastic skeleton from the Dead Zoo to identify:

I suspected that it wouldn’t prove too much of a challenge for most of the regulars here, as it is fairly distinctive – although possibly not all that familiar. However, there is another species that has some very similar convergent features, which did cause some confusion.

The skull is quite elongated and there is a series of simple teeth that line the upper and lower jaw:

This skull shape – plus the powerfully built body – is reminiscent of the first animal to come to mind for anyone with an alphabetical mindset; the Aardvark:

However, as you can see, despite the similarities, there are several differences between these skulls – particularly in relation to the eye (there’s a postorbital process in the Aardvark), cheekbone and teeth (Aardvark teeth are a lot more robust – I talked about them a bit in a post from 2017 if you’re interested).

In terms of differences from the Aardvark, there’s also quite an important feature presnt in the forelimb:

Aardvarks have four front toes, all of which are fairly uniform in size and all have long and robust claws for tearing into termite mounds, but the mystery object has a very odd toe configuration, with every toe different in size and shape, with one enormous sickle-shaped third claw (also useful for demolishing termite constructions).

This is a feature unique to the Giant or Great Armadillo Priodontes maximus (Kerr, 1792):

So well done to Chris Jarvis, who was the first to identify the animal – but I must say that the clue he used to share his knowledge came with a parasitic earworm from which I’m still recovering…

This week I have a mystery object from the Dead Zoo for you to have a go at identifying, that might be a bit on the easy side for some of you:

Despite the fact that I don’t think it will be much of an identification challenge, I just wanted an excuse to feature this specimen, simply because I really like it. Perhaps you can share your thoughts on what it could be using some suitably subtle clue, or perhaps through the medium of rhyme, or even haiku?

Have fun with it!

Last week I gave you this fantastic specimen from the Dead Zoo to have a go at identifying:

It wasn’t a hugely difficult object to identify, given its distinctive narrow serrated bill on a duck-like body, which are hallmarks of the mergansers – a genus of piscivorous ducks:

There aren’t many species of merganser – just six alive today, so on the face of it, there aren’t many to choose from. This particular specimen looks most like a juvenile Red-breasted Merganser, as several people suggested – but it’s not one of those.

This particular specimen is one of two other known merganser species that survived until historic times, but which are now extinct. The other species has no taxidermy specimens to represent it, and is only known from subfossil material from Chatham Island, off the coast of New Zealand.

Our mystery object is one of the very few taxidermy mounts that can show us what the Auckland Island Merganser (Mergus australis Hombron & Jacquinot, 1841) looked like. There are only 27 existsing specimens of this species in the world, most of which are preserved in fluid, and have lost most of their colour as a result – although ours is no doubt a little faded from the natural light in the galleries.

The Auckland Island Merganser is a good example of a species that did not survive contact with humans. Their original distribution was much more widespread on New Zealand and Chatham Island, but the arrival of Polynesian peoples led to their loss everywhere except on Auckland Island.

The arrival of Europeans and the pigs and cats they brought with them to Auckland Island pushed the population to the brink, and then hunting expeditions around the turn of the 19th to 20th century wiped out the rest. This particular specimen was shot on the 5th January 1901. One year and four days later the last pair were killed by the same man – Lord Ranfurly, the Governor of New Zealand.

Ranfurly finished his term as Governor in 1904 and it seems likely that some of the skins of the specimens he collected in New Zealand returned with him. Some went to the British Museum (Natural History), while this one was prepared at “The Jungle” – Rowland Ward’s by shop at 167 Piccadilly, London before coming to Dublin.

It’s saddening to think that a species was pushed over the brink of extinction so deliberately, with no effort to preserve or protect it. Around the same time in North America the Passenger Pigeon became extinct in the wild, but at least the decline of the species had spurred efforts to preserve the remaining individuals in an effort to breed them. Meanwhile in New Zealand, it seems that the scarcity of the Auckland Island Merganser increased the demand for specimens, thereby sealing the fate of the species.

If you want to know more about the life and habits of these birds, New Zealand Birds Online is a great resource, with excellent information, so do check it out.

On a final note, I am currently attending the excellent NatSCA conference in Oxford at the moment, so extinct birds are very much on my mind. Later today I am looking forward to seeing the remains of the last fragments of surviving skin from the Dodo. We once shared our planet with these animals, and while it’s remarkable that we still have these specimens that help us understand what has been lost, it would be better if they had never been lost at all.

Last week, with Easter in the air, I thought this specimen from the Dead Zoo might be appropriate:

Of course, it wasn’t as simple as this being a European Rabbit or ‘Mad March Hare’. Of the 70 or so species of rabbits and hares in the family Leporidae) found around the world, this one is rare and pretty special. In fact, it’s a special national monument in Japan.

As many of you managed to work out, this is an Amami or Ryukyu Rabbit Pentalagus furnessi (Stone, 1900). This species is dark haired (although the fading on this specimen doesn’t make this immediately obvious), they have relatively short ears and their legs are short compared to those of most rabbits. Generally this species is considered to be quite primitive – by which I mean they share a lot of characteristics with their rabbity ancestors who died out in mainland Asia over 2.5 million years ago.

The species is only found on two small islands off the southern end of Japan. This isolation helps explain their primitive status, since they would have been cut off from some of the same pressures that drove their ancestors to extinction. However, now their numbers are in decline and have been for the last century and more.

Where once hunting and trapping were the main threat (and this specimen acquired from taxidermist Rowland Ward in 1912 was likely acquired through that route), the main threats today consist of invasive carnivore species and habitat loss for golf courses.

It’s tragic to think that this species has managed to persist as a ‘living fossil’ for millions of years, only to be pushed towards the brink of extinction for the sake of a good walk spoiled.

Well done to everyone who recognised this unusual and interesting bunny!

Happy (Good) Friday everyone! It’s that time of year when a lot of people in the temperate zones of the Northern Hemisphere are thinking about the springing of Spring and all that entails in terms of flowers blooming, bees buzzing and cute little bunnies doing what they’re famous for.

To mark the upcoming celebration of the pagan fertility goddess Ēostre and the Christian festival of Easter, I have a suitably seasonal specimen from the Dead Zoo for you to have a go at identifying:

Any idea what species this fuzzball might be? I suspect that this may prove more challenging than you might expect, especially since this specimen is very faded by sunlight, so I’m keen to see if anyone can work it out. Have fun!

Last week I gave you this specimen to identify, which came to me as an enquiry, after being found in the sea by a fisherman:

I don’t think it posed too much of a challenge, despite some damage, which has left sections looking a bit different to usual for this skeletal element – which is a section of the lower jaw or mandible.

This piece of the mandible includes the ramus (the rear part of the jaw behind the toothline where it rises up), coronoid process (the section of bone that rises up through the inside of the cheekbones, and where the temporalis muscles attach to power part of the action of the jaw) and the mandibular condyle (the hinging articulation point where the lower jaw meets the rest of the skull).

The scale bar shows that it’s fairly large, and the shape of the coronoid process and articular condyle are what I would consider to be quite distinctive to herbivores, since a long ramus isn’t well suited to resisting forces from struggling prey or meat-cutting bites.

From this point I find it’s useful to check an image I prepared earlier (and by earlier, I mean about 10 years ago):

A quick comparison makes it fairly clear that the mystery object is part of the mandible of a Cow Bos taurus Linnaeus, 1758, based mainly on the shape and orientation of the mandibular condyle.

There are of course species that could possibly turn up in Irish waters, that aren’t on my mandibles photo – in particular, Giant Deer, which Ireland seems to have a lot of. However, I have easy access to those specimens in the Dead Zoo and they have a similar mandibular condyle orientation to a Red Deer.

So well done to everyone who worked it out – I hope my explanation of the anatomy of the rear part of the mandible makes sense and maybe offers some pointers for identifications you might be faced with in the future!

Happy Friday everyone!

This week I have a mystery object for you that came in as an enquiry from a regular donor to the Dead Zoo’s collections. It was found by a fisherman in the Irish Sea, just off Howth, which is a lovely seaside village on a peninsula that marks the northern tip of Dublin Bay :

Any thoughts on what it might be? I suspect some of you will have a pretty good idea, so keep your suggestions cryptic if you can, so everyone has a chance to figure it out for themselves. I hope you have fun figuring it out!

Last week I gave you this skeleton fron the Dead Zoo to test your identification skills:

In retrospect I think I was a little unfair with this one – the photo is not very clear and there is no scale bar, so the identification relied mainly on the context provided by the mount and a lot of deduction. Not an easy task with a rodent, since there are so many different species.

The branch used as a setting for the skeletal mount provided the main and most important clue – it indicates that the species is arboreal. A lot of people picked up on this, with guesses ranging from a flying squirrel to a viscacha. However, the answer is something from a bit closer to home (i.e. Europe).

This is the skeleton of the Edible Dormouse Glis glis (Linnaeus, 1766), a plump (and presumably tasty if you happen to be an ancient Roman), tree-dwelling rodent, with a reputation for somnolence.

This isn’t the first time I’ve featured a dormouse in the blog, although the previous one was a giant extinct example. The Edible Dormouse is the largest species alive today, but it’s still smaller than the fairly diminutive Red Squirrel.

They are fairly well distributed around central Europe, with a small population in Southern England due to escapees from Walter Rothchild’s menagerie in Tring in my home County of Hertfordshire. I’ve heard tell that they can be a bit of a pest in the area, due to their habit of seeking out attics to hibernate in, but then chewing through wires and cables, thus causing fires and broadband outages.

This UK population didn’t arrive until the early 20th Century, so the species that inspired Charles Dodgson (AKA Lewis Carroll) to include his sleepy character was almost certainly the smaller Hazel Dormouse, which occurs in Britain, and which also turned up in Ireland around County Kildare around 14 years ago (and which we have specimens of, thanks to a gift from someone’s pet cat).

I should have either provided a better image or a clue to point you in the right direction for this mystery object, so I feel I’d better apologise for setting this vexatious conundrum and promise to better next time!

Last week I gave you this doe-eyed specimen from the collections of the Dead Zoo to try your identification skills out on:

I didn’t provide a scalebar as I think it would have made it too easy, but even so, it’s clear that the specimen is a very small species of artiodactyl (the group containing pigs, deer, antelope, bovids and a variety of related herbivores).

There were some suggestions that it could be a Dik-dik, but as Adam Yates pointed out, this specimen lacks the large preorbital glands that are very visible in Dik-diks (and makes them look like they got carried away with the eyeliner):

The other popular suggestion for the identity of the mystery object was a Java Mouse-deer (or Javan Chevrotain), which is the smallest ungulate alive. However, while that’s exactly what it says it is on the label, the location of collection rings alarm bells for me:

There are two species of chevrotain found in Singapore, and the Javan species is not one of them.

Of the two, one is the Greater Mouse-deer and the other is the Lesser Mouse-deer. The Greater, as you probably guessed, is on the large side for a chevrotain, weighing in between 5 and 8kg. This species also has a dark stripe from its nose to its eye, which is missing from the mystery object.

The Lesser Mouse-deer Tragulus kanchil Raffles, 1821 lacks the dark stripe and is almost as tiny as the Javan Mouse-deer, making it the most likely candidate for the mystery object:

This specimen not only has that likely identification error on the label (easily done considering the complexities of chevrotain taxonomy across Southeast Asia), but it had somehow also had a completely incorrect label associated with it in the past, which said it was a Siberian Musk Deer – a species that’s on the small side, but by no means as tiny as this.

This specimen was of particular interest at the end of last year, when we had a visit by a group of researchers from Singapore, who are undertaking a fantastic project to digitise specimens collected from Singapore that are held in museum collections all around the world. The project is called SIGNIFY and the team were not only absolutely lovely people, but they achieved a huge amount of research and detailed imaging work in a very short time:

The SIGNIFY project has huge value for helping to understand the historic baseline biodiversity of Singapore prior to industrialisation, but it also helps foster links between organisations and allows the inextricably linked social and personal histories of collectors to be explored. I loved getting a chance to spend time with the team, learning more about their project and the collections I care for. It also turns out that we have a wealth of spiders from Singapore that still need to be investigated, so I really look forward to welcoming the team back soon!

Last week I shared this fuzzy critter as mystery object for you to identify:

It was probably a bit of a mean one, as I didn’t provide a scalebar. It’s also a species from a group of small carnivores that contains over 30 species that can look quite similar, and (perhaps most importantly) the specimen is old and very faded from being on display in a gallery space with lots of light for the last 100 years or more.

Regardless, Chris Jarvis figured it out (after an initial near miss), while I believe that Joe Vans cheated by checking out the 3D tour of the Dead Zoo. Most other comments on social media came close, with a lot of people working out that this is a Mongoose, but then not quite getting the species.

This specimen is a Common Kusimanse Crossarchus obscurus G. Cuvier, 1825. These are also known as the Long-nosed Kusimanse, as their snout is a bit more elongated than that of most other Mongooses (or should that be Mongeese?):

The Common Kusimanse is one of the African Mongooses in the Subfamily Mungotinae. They are a good bit shorter than most of the other species of Mongoose – for comparison here’s this specimen next to a Small Indian Mongoose (well, that’s what the label says, although I have some doubts):

They are normally a dark brown colour, like this example:

However, the Dead Zoo specimen is now bleached blonde, so I’m not surprised that this identification was tricky. Fading leads to all sorts of issues for the accurate representation and identification of species, to the point where the Giant Panda on display in the building had to be dyed black in places a few years ago, because it had ended up looking like a Polar Bear cub due to the sun damage.

At the moment that’s no longer an ongoing issue in the Museum, as a temporary floor has been installed just beneath the old glass ceiling, to allow investigations on the roof space to take place – this blocks almost all of the natural light. This has been great for conditions in the building, as it no longer heats up like a greenhouse on sunny days, and the bleaching of the specimens has been put on hold.

At some point the tempoprary floor will be removed, but I sincerely hope that a more permanent solution to the light issue will have been put in place by then. Still plenty of work to be done to get to that point though!

Last week, I gave you this shiny blob to have a go at identifying:

There wasn’t much to go on, since it is just a blob that looks like a chunk of hardened tar, but it is in fact a rare and valuable natural material. It’s actually a small piece of ambergris.

Ambergris has always maintained an air of mystery, since it’s formed deep within the bile duct of a Sperm Whale and its function in the animal is still only suggested rather than fully understood. General agreement seems to be that this tarry substance provides protection for the intestines from the sharp beaks of the squid that Sperm Whales prefer to eat.

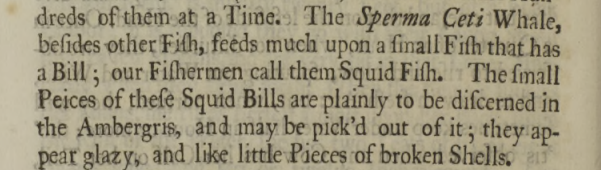

Evidence for this comes from the fact that squid beaks are often found embedded in ambergris – an observation recorded from as early as 1725:

This letter goes on in some detail about various whale species, offering details of their economic yield in terms of barrels of oil, quantity of whalebone (baleen) and medicinal uses of teeth, as well as some aspects of their biology. When the discussion gets onto ambergris, much of the focus is on its location in the whale and the method of extraction (N.B. it’s not pretty.)

Of course, the suggested function of ambergris as a mechanism to aid the passing of sharp objects through the gastrointestinal tract would indicate that ambergris also might emerge naturally, and doesn’t necessarily need to be ripped from an unwilling victim.

However, evidence for this is quite hard to find, since it’s remarkably difficult to follow a Sperm Whale and keep track of its bowel movements or regurgitations (which have also been suggested as an exit route for these masses of indigestible items). What is known is that ambergris can be found floating at sea and washed up on beaches, sometimes persisting for years (there has even been fossilised ambergris discovered in Italy).

This non-invasive method of harvesting ambergris by beachcombing may not be hugely efficient, but it supplies the majority of the ambergris now used in perfume manufacture. Yes, you heard me right.

Human interest in ambergris may seem surprising given its somewhat revolting source, but as we all know, humans are pretty weird when it comes to making use of the fruits of nature, especially when searching for ingredients for perfume – just think of the African Civet and its anal excretions.

The natural complex aromatic compounds found in waxy substances like ambergris and civet musk provide long-lasting base odours that have played an important role in creating perfumes for centuries. Modern chemical synthesis of similar products has taken over to a large extent, but the naturally occurring compounds are still in use today.

This particular blob of ambergris was photographed when we were getting it out for sampling to inform a rather different line of scientific questioning, since there is still a lot to learn about this very unusual natural material.

This week I have a specimen that we recently had an enquiry relating to at the Dead Zoo:

Do you have any ideas what this shiny blob might be? If you’re confident in your blob identification skills, maybe try to keep your answer cryptic, so everyone gets a chance to work it out for themselves. Have fun!

Last week I gave you this mystery object from the Dead Zoo as a way to kickstart 2024:

While it does indeed look a bit like an old Roman shoe (thanks Adam Yates – I will never unsee that now), these are in fact the gill rakers from a Basking Shark Cetorhinus maximus (Gunnerus, 1765).

This was spotted early on by Dennis Nieweg and several other people worked it out, both here and on social media (Mastodon, Bluesky and LinkedIn). However, there were also a lot of suggestions of whale baleen, which is not surprising, since they perform the same function in filter feeding on plankton.

Basking Sharks are the second largest fish on the planet reaching around 8m in length, although they trail behind another far bigger filter feeding cartilaginous fish, the Whale Shark, by quite a margin (the Whale Shark can be twice as long). These two species have little overlap in their ranges – with the Whale Sharks in tropical waters and Basking Sharks in the temperate marine zones:

Basking Sharks occur in the waters around Ireland, where this specimen was collected. The Dead Zoo also has a full taxidermy specimen collected off the coast near Galway in 1870, which has pride of place hanging from the ceiling in the Ground Floor Irish Room:

At the moment this specimen appears to be wearing a nappy – and this isn’t intended to capitalise on the popularity of the “baby shark” earworm, it’s an emergency stabilisation of the specimen. This became necessary after the rudimentary taxidermy (the skin is basically nailed to a barrel-built internal frame along the top of the specimen) failed in last summer’s unusually humid conditions and the skin started to fall off.

A proper repair will eventually be undertaken, but that will require lowering the specimen from the ceiling and transporting it offsite so it can be fully assessed and conserved. This is a big job, and this year we will be kicking off the next stage in a major capital project in the Museum, to deal with lack of physical access and problems with the environment – including the high humidity issue, so it’s just one big job alongside many, many others.

As the project gains momentum I hope to be able to share some of the work that takes place here on Zygoma, as well as through social media channels – so be sure to watch this space for updates. Here’s looking forward to an exciting 2024!

Last week I gave you some festive-looking specimens to have a go at identifying:

I thought these were some specimens in the care of Andy Taylor, FLS, but this was my error – Andy sent me the images to suggest the species as mystery objects, but I didn’t realise that he hadn’t photographed his specimens to use at that point. These images are actually from a paper (referenced above) that discusses the species and the blue-green colour is a stain added to allow the growth rate of the tubeworms to be calculated (spoiler alert – it’s very slow).

Here are Andy’s specimens:

A bit less colourful, but the tubes retain the same structure, with those clearly defined rings.

As Adam Yates said in the comments, these are specimens of Lamellibrachia luymesi van der Land & Nørrevang, 1975. They have similarities to other genera, such as Hilary Blagbrough’s suggestion of Ridgeia and katedmonson’s suggestion of Riftia.

Species like Riftia pachyptila are from hydrothermal vents and that nutrient rich and high temperature environment gives their symbiotic bacteria a boost that allows Riftia to be the fastest growing invertebrate, reaching around 1.5m long in just a couple of years. This is useful as it allows rapid colonisation of these ephemeral volcanic environments that occur at mid-ocean ridges.

On the flip side, Lamellibrachia luymesi tubeworms live in cold seeps of hydrocarbons in the deep ocean, where their symbiotic bacteria have to work at temperatures of 4°C or less, making their energy production a slow process. Consequently, L. luymesi are one of the slowest growing invertabrates, taking around 125 years to reach 1.5m long. Cold seeps are much more stable than the hydrothermal vents however, so L. luymesi have been found to continue growing up to 3m, taking around 250 years, and therefore being among the longest lived invertebrates (and indeed animals) on the planet.

Some might suggest that there’s a lesson to be learned here about “slow and steady winning the race”, but slow growth would be disastrous for a species that relies on a rapidly changing environment. Both species are remarkably adapted to their environment and neither would do well in the other’s place.

It’s worth noting that both of these remarkable organisms are only as successful as their symbionts allow them to be, so if there’s any lesson to be shared, it’s probably that the value of teamwork should never be underestimated.

On that (somewhat cheesy) note, I would like to thank Andy once again for sharing his collections. I’ll be back in the New Year with another Mystery Object – I hope you enjoy the celebrations!