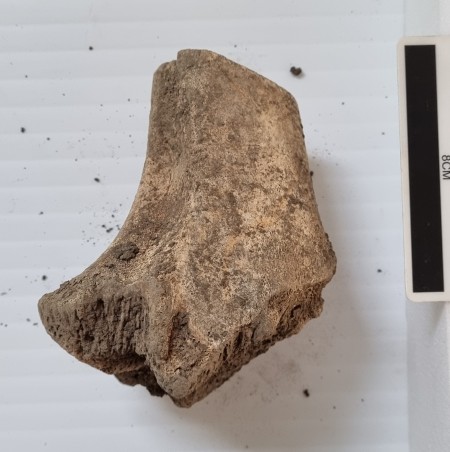

Last week I gave you this genuine mystery object from Rohan Long, curator of the comparative anatomy collection of the Harry Brookes Allen Museum of Anatomy and Pathology at the University of Melbourne:

This specimen may have been collected by Frederic Wood Jones, a British comparative anatomist who headed up the Anatomy Department at the University of Melbourne in the 1930s. This may mean it could have come from almost anywhere, given Wood Jones’ links with other anatomists.

So all we really have to go on is the morphology of the object.

It’s clearly made from long section of quite highly vascularised bone:

It seems to be missing the smooth surface normally seen on bone, but that can be caused by a variety of factors, from disease and infection in the live animal to weathering after it’s been dead for a while.

The ends of the bone don’t have any indications of an articular surface:

The larger end has a bit of a hollow, but the smaller end appears to be broken and you can see a hollow core to the bone.

Overall, the shape is not really reminiscent of any long bone I can think of. It lacks a normal articular surface at the unbroken end and it has no crests or ridges that I would normally expect muscles to attach to. It tapers quite consistently and has a slight curve.

My first thought was shared by others in the comments, with Chris Jarvis getting in first with the simple but effective pun:

Oooh! Sick!

Chris Jarvis August 4, 2023 at 12:37 pm

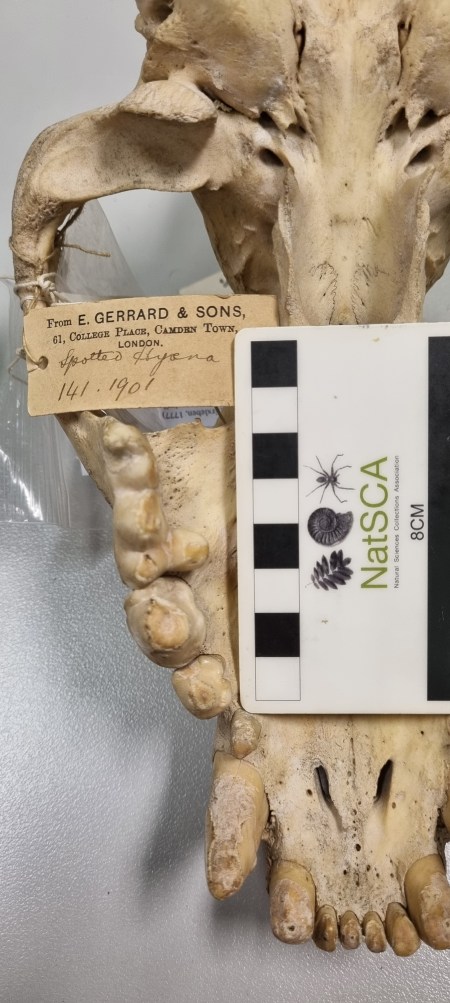

This is of course a reference to Oosik, which is the name in Native Alaska Languages for the baculum or os penis of a Walrus Odobenus rosmarus (Linnaeus, 1758).

There are some differences between this specimen and some of the other Walrus bacula I’ve seen and which show up in an image search, but there are a variety of possible explanations for that.

One is simply that Walrus bacula are quite variable. They can vary significantly through the life of the animal as it develops, but it can also vary quite a lot between individuals. If you spend as long looking at Walrus penis bones on the internet as I have (what on Earth happened to my life?!) then you’ll notice that some have a strong double curve while others can be almost straight, others are thick and some are quite thin.

This variability is also seen in other pinnipeds with a high degree of sexual dimorphism, like Sealions and Elephant Seals.

So while it’s hard to be 100% certain of the identification, I think it is the most likely solution to this mystery.

I hope you had fun with this one!