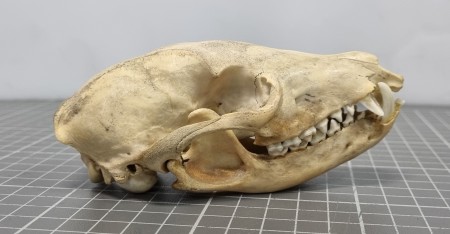

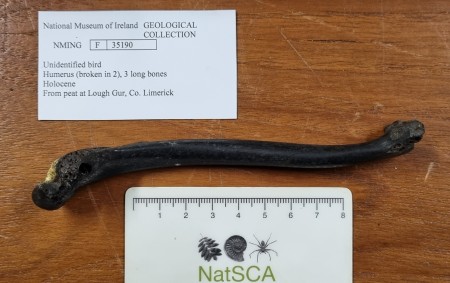

Last week, I gave you this shiny blob to have a go at identifying:

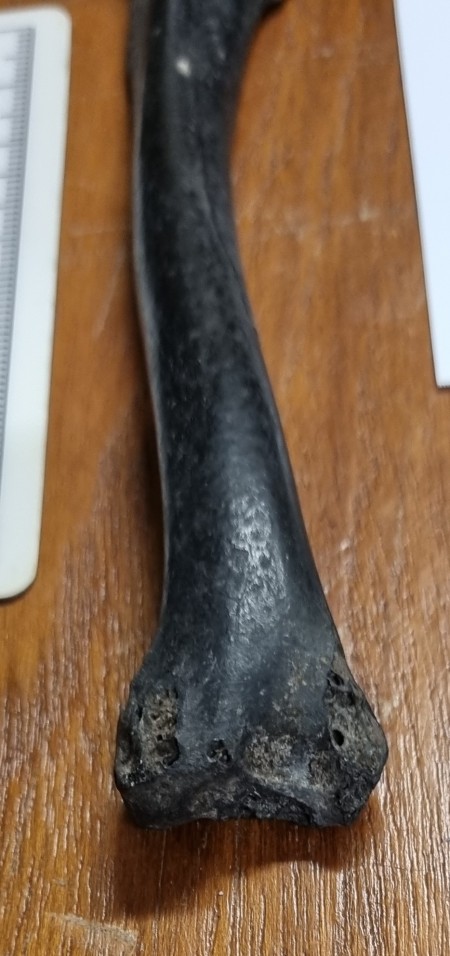

There wasn’t much to go on, since it is just a blob that looks like a chunk of hardened tar, but it is in fact a rare and valuable natural material. It’s actually a small piece of ambergris.

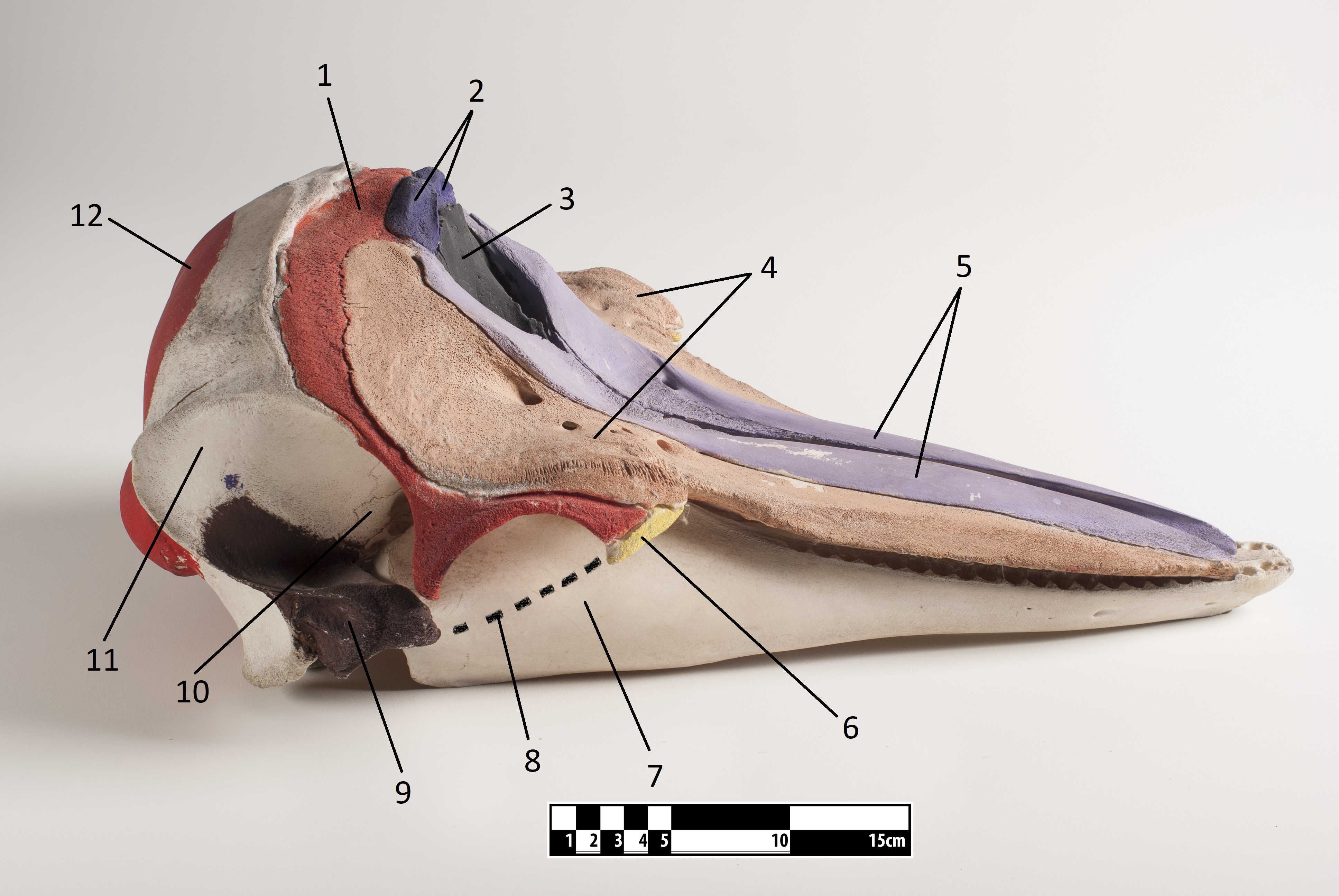

Ambergris has always maintained an air of mystery, since it’s formed deep within the bile duct of a Sperm Whale and its function in the animal is still only suggested rather than fully understood. General agreement seems to be that this tarry substance provides protection for the intestines from the sharp beaks of the squid that Sperm Whales prefer to eat.

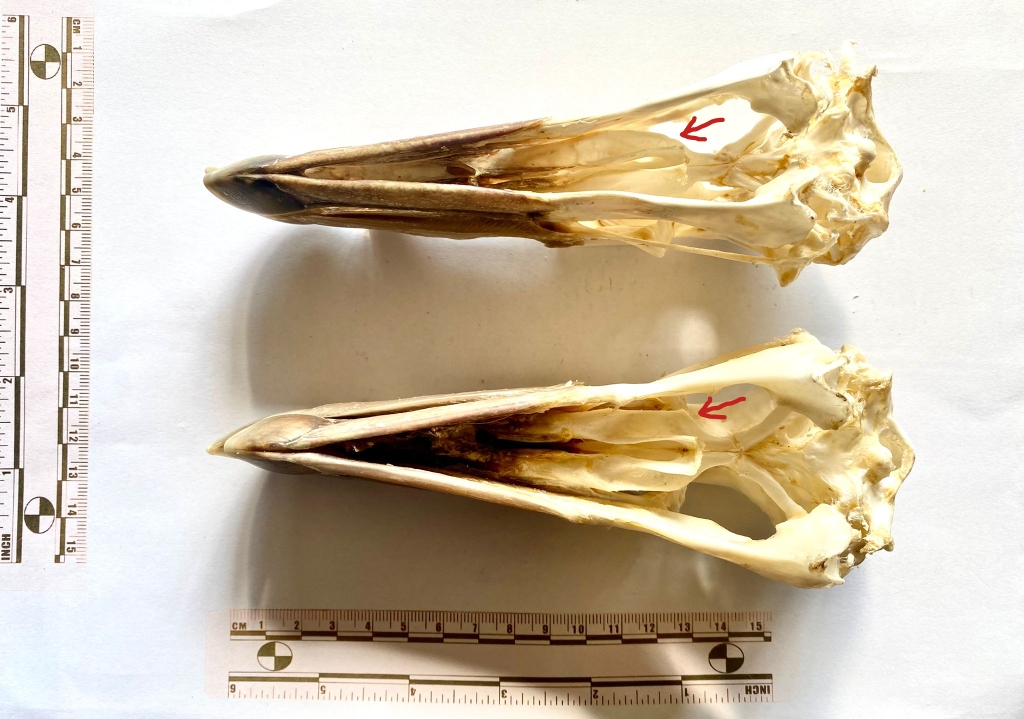

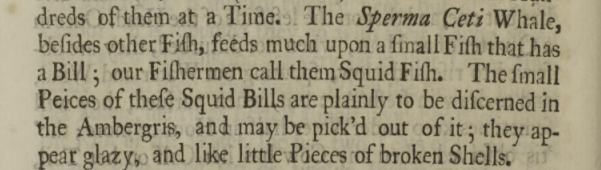

Evidence for this comes from the fact that squid beaks are often found embedded in ambergris – an observation recorded from as early as 1725:

Published:30 April 1725 https://doi.org/10.1098/rstl.1724.0053

This letter goes on in some detail about various whale species, offering details of their economic yield in terms of barrels of oil, quantity of whalebone (baleen) and medicinal uses of teeth, as well as some aspects of their biology. When the discussion gets onto ambergris, much of the focus is on its location in the whale and the method of extraction (N.B. it’s not pretty.)

Of course, the suggested function of ambergris as a mechanism to aid the passing of sharp objects through the gastrointestinal tract would indicate that ambergris also might emerge naturally, and doesn’t necessarily need to be ripped from an unwilling victim.

However, evidence for this is quite hard to find, since it’s remarkably difficult to follow a Sperm Whale and keep track of its bowel movements or regurgitations (which have also been suggested as an exit route for these masses of indigestible items). What is known is that ambergris can be found floating at sea and washed up on beaches, sometimes persisting for years (there has even been fossilised ambergris discovered in Italy).

This non-invasive method of harvesting ambergris by beachcombing may not be hugely efficient, but it supplies the majority of the ambergris now used in perfume manufacture. Yes, you heard me right.

Human interest in ambergris may seem surprising given its somewhat revolting source, but as we all know, humans are pretty weird when it comes to making use of the fruits of nature, especially when searching for ingredients for perfume – just think of the African Civet and its anal excretions.

The natural complex aromatic compounds found in waxy substances like ambergris and civet musk provide long-lasting base odours that have played an important role in creating perfumes for centuries. Modern chemical synthesis of similar products has taken over to a large extent, but the naturally occurring compounds are still in use today.

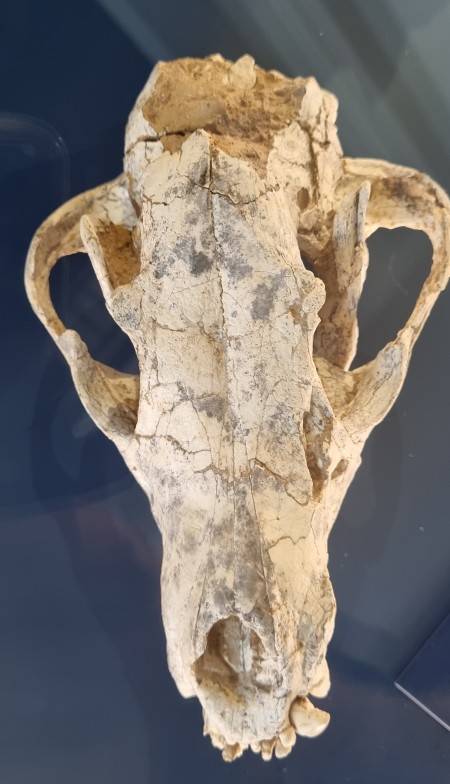

This particular blob of ambergris was photographed when we were getting it out for sampling to inform a rather different line of scientific questioning, since there is still a lot to learn about this very unusual natural material.