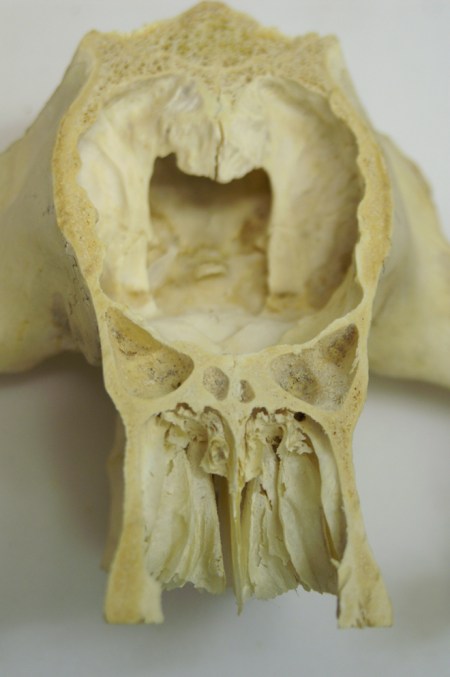

The mystery object on Friday was chosen by Taylor, a work experience student who assisted me in the collections last week. He picked a particularly tricky specimen:

However, I am pleased to say that Jake immediately spotted that it was a skull that had been sectioned and after some questions and some close guesstimates by Henry Gee (who was working through the various families within the Carnivora), it was eventually correctly identified by Jeremy, who worked out that it was in fact from a lion, Panthera leo (Linnaeus 1758). Jeremy suggested that it might be a tiger before he hit on the correct answer, which gave me pause for thought (or given the context perhaps that should be paws for thought… or perhaps not).

Distinguishing between lion and tiger skulls is not an easy business, even for a professional morphologist. As a result, if there is a skull that lacks good data there is often the possibility that it has been misidentified (something I have come across in a variety of museums). So here’s a helpful hint should you ever need to spot the difference between a tiger and a lion skull:

As you can see, there is a region near the top of the front of the skulls where several bones (the nasals, maxilla and frontals) meet in a vaguely W-shaped pattern of sutures. In lions tigers the centre of the W (the top-most point where the nasal bones meet the frontals) is above an imaginary line between the sides of the W (the tops of the sutures between the maxilla and frontal) – the diagram hopefully makes that a bit clearer! In the tiger lion the centre of the W is either on a line with or below the sides of the W (meaning that the tiger lion’s sutures look more like w). This pattern of sutures is quite variable, but so far I have never found a confirmed tiger skull that hasn’t had the nasals extending beyond the maxilla (with an a sample size of at least 30).

The simplest way to think of it is that lions tigers have nasal bones that extend further up the head than tigers lions. This could potentially be because lions generally live in drier habitats than tigers, so they may need a larger area for the attachment of nasal turbinates. These turbinates are thin folds of bone inside the nose that help reduce water loss during breathing. Perhaps more on them another time… [apologies for all the strike-throughs, Jack Ashby at UCL muesums reminded me that the sutures work the other way round – my excuse is that I was doing this in a hurry when tired. Cheers Jack!]

So well done to everyone who took part and many thanks to Taylor, who managed to baffle the editor of Nature with this particular object – no mean feat given Henry’s pinpoint accuracy last week!

Paolo: thanks, this is a great relief to me, now I will know how to distinguish between a lion’s skull and a tiger’s!

Make sure you look at the updated version!

Excellent! Looking forward to next week’s object.

Excellent tip (though it does depend on you not slicing the top off the cranium before attempting identification ;-))

Do we really have to wait until Friday for the next Friday Mystery Object? I guess I’ll have to be patient.

Good point – I meant to mention that I’ve looked at the top of the skull and it is indeed a lion. At least I gave you props for getting tiger!

I’m afraid that once a week is the best I can manage on the mystery object front – you could always look through past objects and have a go at identifying them – I try hard to make sure there aren’t too many spoilers giving away past objects and I am happy to answer questions on old posts.

I’d better keep my eyes peeled for this week’s object!

Hi Paolo

Excellent object, though I’m afraid to say I think you’ve got it the wrong way round – the top of the nasals extends higher above the top of the maxillae in a tiger than in a lion.

Please let me know if it’s me who’s wrong cos all the specimens in the Grant will be incorrect!

I knew I’d do that. It was pretty much a certainty… the trouble with doing these things in a rush!

I’ll get on with fixing it now.