Last week I gave you a mystery object that came wrapped in this intriguing box:

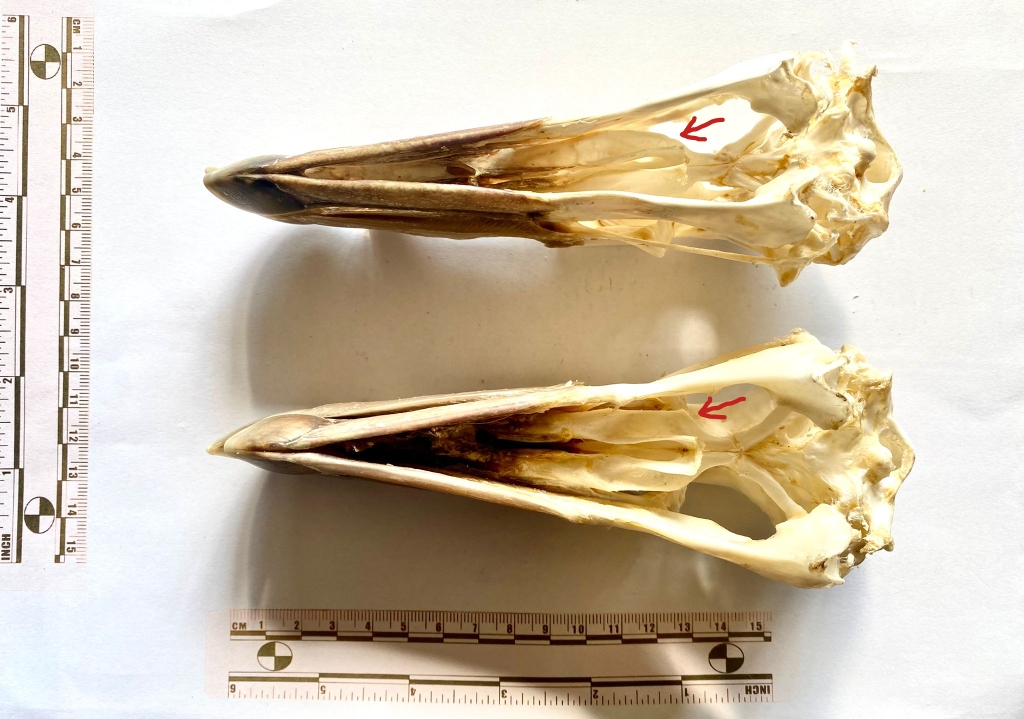

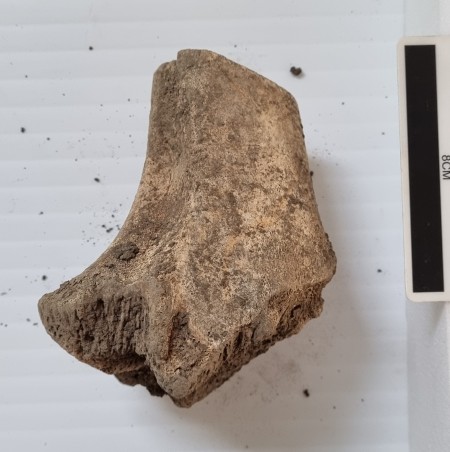

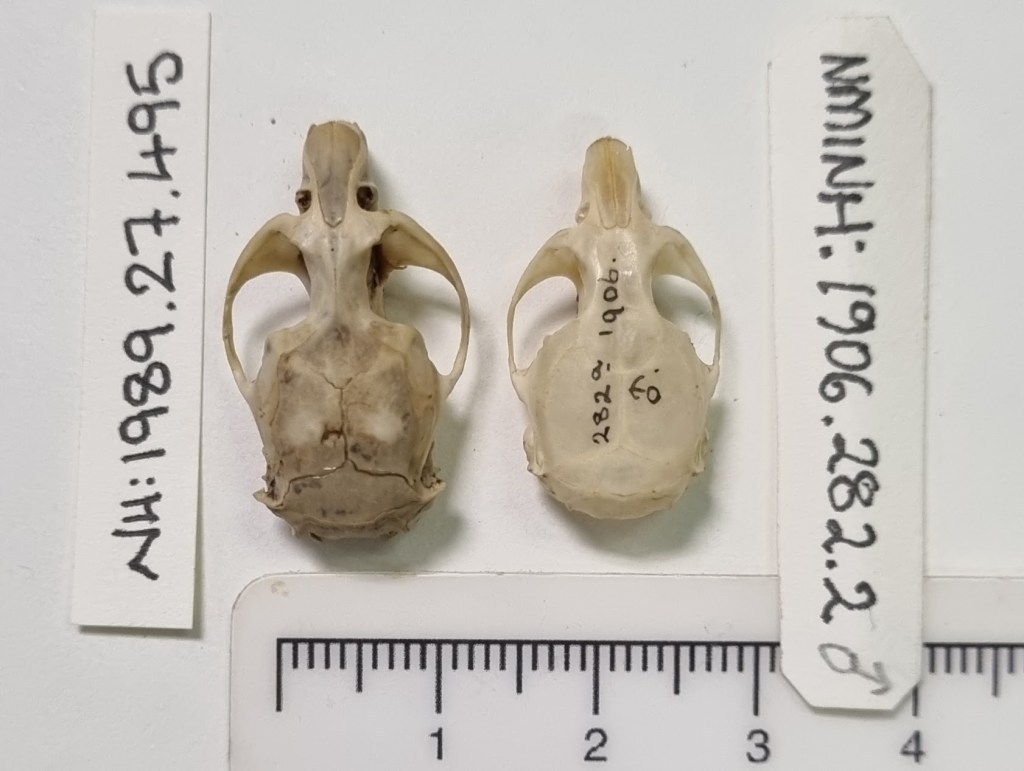

The discovery inside was this:

Definitely not a Poptart.

This is a discovery made by 10 year old Anna, who found it when digging in the garden with her Dad, and she’s keen to know what it’s from. In fact, she’s hoping it’s from a new species of dinosaur, so it can be give the excellent name Annasaurus (although I believe such a creature already exists in the world of Doctor Who).

While the bone is pretty big, unfortunately it’s not from a dinosaur, but a large mammal. The cut surface looks very neat and that suggests that it’s been passed through a band-saw, probably by a butcher:

This would suggest it comes from one of the commonly eaten species, such as Sheep, Pig or Cow – although It is possible that butchered bone would come from another animal, such as Goat, Horse or a species of deer.

However, the size immediately reduces the likely suspects down a lot. It’s bigger than any Sheep or Goat bone I’ve encountered, so the focus is on Horse and Cow, although Red Deer and Pig are worth a look too,

Normally my first question is “which bone is it?” and in this instance it’s actually a bit harder than usual because it’s both cut and from a young animal, so the articular surface from the top of the bone (or epiphysis) hadn’t fused yet and is missing.

This means we’re looking at the neck section of the bone (the metaphysis), which is harder to find good material to compare against. However, with common species there are at least some excellent online resources to see full bones from a variety of angles that can help build up a picture of what to look for.

In this case I used OsteoID, which has good coverage of skeletal elements for a lot of mammal species that commonly occur in North America. I already recognised that this was from around the knee area, so I first checked if we are dealing with the leg section above the knee (distal femur) or the bit below (proximal tibia). Wouter van Gestel suggested shin bone (tibia) in the comments and I came around to that interpretation, so that’s what I originally went with.

However, Christian Meyer later suggested it was more likely to be distal part of the femur, and after looking at the specimen in hand, I find myself in agreement.

On to the species! It’s a good bit broader than the Pig femur (especially considering that the epiphysis is the broadest section of the bone and that’s missing here).

The shape of the metaphysis is too robust for deer, who have a more sharply defined ridge that runs into the main shaft of the bone (or diaphysis):

But it’s not as robust and it tapers more in the metaphyseal area than you’d expect from a Horse..

So after a good bit of comparison, I’m fairly certain that this is the distal metaphysis from the femur of a Cow Bos taurus Linnaeus, 1758.

I will write back to Anna to let her know about her discovery and while it may not be a dinosaur, it’s still an interesting find, so I hope she’s not too disappointed!