Last week I gave you this mystery object found by the family of one of my colleagues to have a go at identifying:

Adam Yates got the ball rolling with some key observations about this skeletal element that provides a handy set of clues to look for when assessing vertebra:

The element is easier than than the taxon. It is a thoracic vertebra from a mammal because it has zygapophyses (so therefore not a fish), flat centrum faces (so therefore not bird or reptile), and rib articulation facets (so therefore not from the neck, lumbar or tail regions). Which mammal is less easy, I’m pretty sure it is isn’t a relative of flipper, but that’s all I’ve got now.

Adam was also right in flagging that it’s not from a cetacean – their transverse processes are longer and less robust than we see in this mystery specimen. However, this bone was found on the beach on Achill Island, so there’s a good chance it’s from a species that’s frequently in the water.

Then Joe Vans, Kat Edmonson and Adam got stuck in with consideration of the possible species and specific thoracic vertebra, and as part of that there was reference to images from John Rochester’s Flickr pages. As far as I’m concerned, John’s pages are some of the best resources available for osteological comparison and I use them regularly.

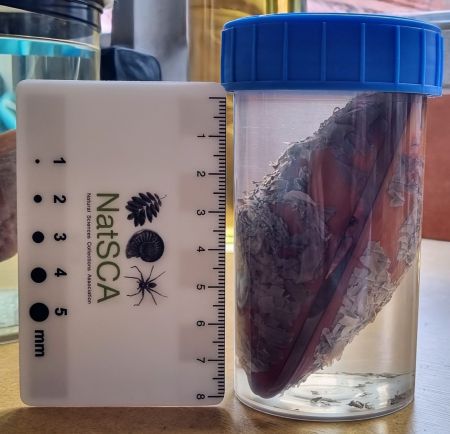

The discussion ended up converging on the 5th thoracic vertebra (or T5 as it would be commonly referred to) of a Harbour Seal, based on specimens imaged by John here: https://www.flickr.com/photos/jrochester/14181517647 – best compared to this image of the mystery specimen:

This could well be correct, but I personally think it may be from a different species of seal. The size is fairly large (based on the hand that provides some scale), yet the epiphyses of the articular surfaces are not fully fused, suggesting that this is from a subadult animal:

This suggests to me that the animal had some more growing to do before reaching full size, which may impact on some of the features, but it also makes me think that the vertebra is probably on the smaller end of the size range for the species.

For me that would suggest a Grey Seal Halichoerus grypus (O. Fabricius, 1791) and looking at another of John’s pages: https://www.flickr.com/photos/jrochester/24441096790/in/photostream/ I would expect it to be in the T6 or T7. This also tracks for me in terms of the shape of the neural canal, which seems narrower and taller (generally more square) in the Grey Seal compared to a broader and perhaps more triangular neural canal in the Harbour Seal.

I suspect a measurement of the size would help confirm one way of the other, so I’ll see if I can get that to be sure. I hope you enjoyed the challenge of working this out, and I’d love to hear your thoughts if you think it could be something else!