I’d like to start by wishing you all a very Happy New Year! This week’s mystery object is from the Dead Zoo in Dublin:

Any idea what this gnarly looking object might be?

I look forward hearing your thoughts!

Last week I gave you some festive-looking specimens to have a go at identifying:

I thought these were some specimens in the care of Andy Taylor, FLS, but this was my error – Andy sent me the images to suggest the species as mystery objects, but I didn’t realise that he hadn’t photographed his specimens to use at that point. These images are actually from a paper (referenced above) that discusses the species and the blue-green colour is a stain added to allow the growth rate of the tubeworms to be calculated (spoiler alert – it’s very slow).

Here are Andy’s specimens:

A bit less colourful, but the tubes retain the same structure, with those clearly defined rings.

As Adam Yates said in the comments, these are specimens of Lamellibrachia luymesi van der Land & Nørrevang, 1975. They have similarities to other genera, such as Hilary Blagbrough’s suggestion of Ridgeia and katedmonson’s suggestion of Riftia.

Species like Riftia pachyptila are from hydrothermal vents and that nutrient rich and high temperature environment gives their symbiotic bacteria a boost that allows Riftia to be the fastest growing invertebrate, reaching around 1.5m long in just a couple of years. This is useful as it allows rapid colonisation of these ephemeral volcanic environments that occur at mid-ocean ridges.

On the flip side, Lamellibrachia luymesi tubeworms live in cold seeps of hydrocarbons in the deep ocean, where their symbiotic bacteria have to work at temperatures of 4°C or less, making their energy production a slow process. Consequently, L. luymesi are one of the slowest growing invertabrates, taking around 125 years to reach 1.5m long. Cold seeps are much more stable than the hydrothermal vents however, so L. luymesi have been found to continue growing up to 3m, taking around 250 years, and therefore being among the longest lived invertebrates (and indeed animals) on the planet.

Some might suggest that there’s a lesson to be learned here about “slow and steady winning the race”, but slow growth would be disastrous for a species that relies on a rapidly changing environment. Both species are remarkably adapted to their environment and neither would do well in the other’s place.

It’s worth noting that both of these remarkable organisms are only as successful as their symbionts allow them to be, so if there’s any lesson to be shared, it’s probably that the value of teamwork should never be underestimated.

On that (somewhat cheesy) note, I would like to thank Andy once again for sharing his collections. I’ll be back in the New Year with another Mystery Object – I hope you enjoy the celebrations!

This week’s mystery object is a guest specimen from regular contributor Andy Taylor, FLS, chosen for its seasonal colours:

Any ideas what these living party decorations might be?

As ever, you can pop your questions, thoughts, and suggestions in the comments below – no need for cryptic clues this time around as it’s a tricky one!

With that seasonal conundrum to consider, I wish you all a wonderful holiday weekend!

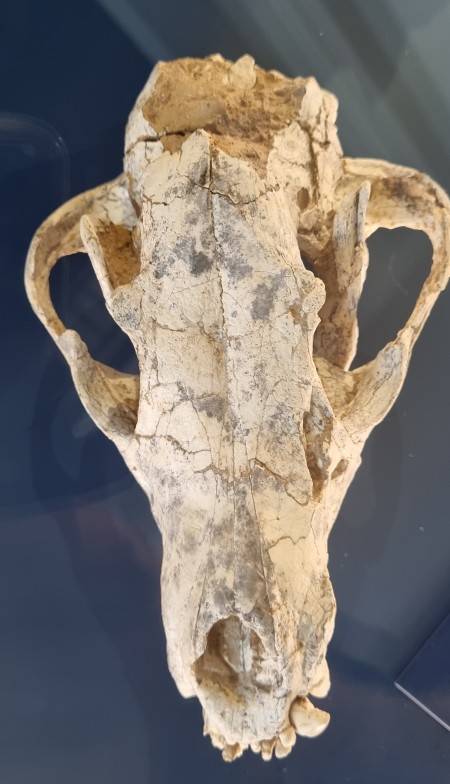

Last week I gave you this unidentified skull from the collections of the Dead Zoo:

I say it was unidentified, but in a strange quirk of coincidence I actually did identify this skull three years ago, just a month before the start of the Covid Pandemic (which might explain why I never had a chance to update the record).

Not only did I identify it, the specimen also made it into the blog exactly 100 mystery objects ago.

I think the specimen is most likely to be the skull of a White-nosed Coati Nasua narica (Linnaeus, 1766), for the reasons I outlined back in 2020. So well done to Leon and Chris for recognising this cousin of the Raccoon from South and Central America and the southern parts of some North American states .

Coatis have quite distinctive upper canine teeth, that look almost like short tusks. These are useful for defence from other Coatis, but they are not very well adapted for subduing larger prey. This isn’t really a problem for Coatis, since they mainly feed on invertebrates, fruit and small vertebrates that they undcover during their energetic foraging.

So I apologise to everyone for repeating a specimen – this is the first time this has happened (and hopefully the last)!

This week I’m continuing with skulls from the collections of the Dead Zoo, and this one was sitting in the “Unidentified” drawer:

Do you have any ideas what this might be? I suspect that some of you will be familiar with this, so perhaps it’s time for some cryptic suggestions in the comments. Have fun!

Last week I gave you this neat little skull to have a go at identifying, from research collections of the Dead Zoo in Dublin:

I wasn’t surprised that everyone in the comments worked out that this is the skull of some sort of fox, but I was equally unsurprised that nobody worked out the species. Generally speaking, most people immediately think of the near ubiquitous Red Fox or perhaps Grey Fox (or Gray Fox to our American friends), but there are plenty of others – 24 species commonly referred to as “fox” and 12 species of “true fox” in the genus Vulpes.

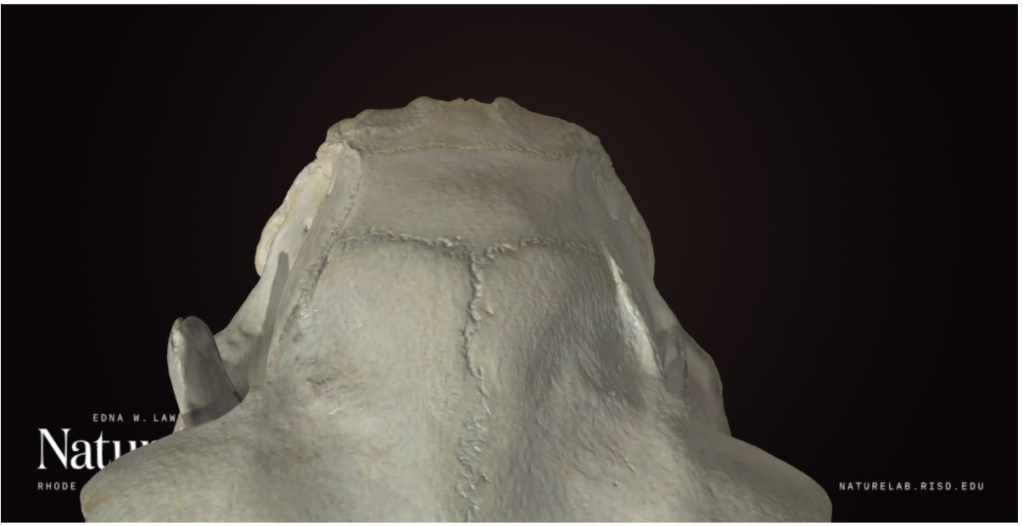

This particular specimen has a sagittal crest that forms a lyre-shape – normally something associated with the Grey Fox:

However, this feature can occur in other species, often in females or subadults, where the surface of the bone has not finished remodelling at the margin of the attachment of the temporalis muscles (those are the ones that connect to the lower jaw from the sides of the cranium and are responsible for the operation of the lower jaw during powerful biting).

However, in this specimen the muzzle is more tapered and the postorbital constriction is relatively broad. All of these point away from the Grey Fox.

With foxes there can be a lot of similarities between the skulls of species, with all the usual compounding issues of sexual dimorphism, age and regional variation. However, size can give some clues, and things like the relative size of the external auditory meatus (also known as the ear-hole), and the shape of the auditory bulla, are useful for differentiating between species.

With a bit of patience, a bit of pattern recognition, and a resource with good images of specimens, like the Animal Diversity Web, it is possible to work out what you’re looking at.

In this case, the mystery object is a Swift Fox Vulpes velox (Say, 1823).

These North American foxes are smaller than the Red or Grey Fox, but a bit bigger than their close cousin, the Kit Fox. They live in grasslands and praries, where they prey on rodents, birds, reptiles and pretty much anything they can find – including insects, fruit and grasses.

As with many species, the Swift Fox has declined due to changing land use and the systematic persecution of predators in the first half of the 20thC. In fact, it was wiped out in Canada around this time, although it was subsequently successfully reintroduced and numbers have increased.

So watch out for those foxy skulls – there are more species to consider than you might think and they can be tricky to identify without reference resources. I hope you enjoyed this little detour down the fox hole!

For the first time in quite a while, I managed to escape from my desk and spend a little time in the collections of the Dead Zoo. The main reason was to facilitate access for researchers doing some really cool projects, but it also gave me a chance to spend a little time exploring the collections I’m responsible for.

In one of the cabinets I spotted this skull, and I thought it might make a good mystery object:

So, do you have any thoughts on what this might be? As ever, you can leave your questions, observations and suggestions in the comments section below. I hope you enjoy this specimen as much as I did!

Last week I gave you this specimen from the Dead Zoo to have a go at identifying:

Evidently it was a bit too easy, since everyone who commented not only worked it out, but took the time to come up with clever cryptic clues to reveal the identity. The first was Tony Irwin with:

I suppose that a pencil sketch of this would qualify as a labradoodle?

Tony Irwin November 10, 2023 at 9:34 am

This is a specimen of Labrador Duck Camptorhynchus labradorius (Gmelin, JF, 1789), an endemic North American duck that has the dubious honour of being the first American species to be pushed into extinction following the European invasion of the continent. The exact reasons for the extinction are unsure, but between the adult birds being shot or caught on fishing lines, their eggs being over-exploited as a food source by settlers, and competition with humans for mussels and other marine molluscs, the already small populations were quickly reduced to nothing.

The last sighting was in 1878, but the museum bought this specimen in 1892 for the princely sum of £30-0-0 (that’s the equivalent of about €5,376 in today’s money). It had passed through a few pairs of hands before the Museum got hold of it, but we’re fortunate in knowing that the specimen was brought to Ireland in August 1838 from New York by Lt. W. Swainson R.N. who was in command of The Royal William, a paddle steamer in the service of the City of Dublin Steam Packet Co.

Only 55 specimens of Labrador Duck are known from museums around the world, so all information about them is valuable, especially when you consider how scarce and irreplacable they are. Specimens like this really hammer home the responsibility we have as museum professionals who are responsible for their care.

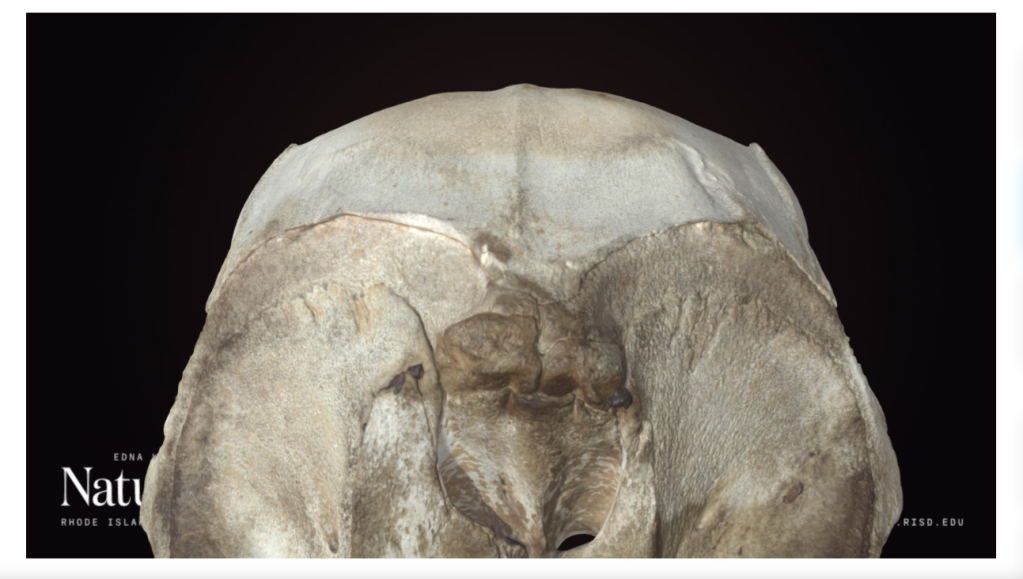

Last week I gave you this 6 million year old fossil skull to have a go at identifying:

The specimen is on display in the geology galleries of the Natural History Museum at the University of Oslo (which is well worth a vist). However, this did mean the photos provided weren’t quite as good as I’d like, particularly notable being the lack of a scale bar (sorry!)

Even without a scale, consensus shifted towards this being some kind of hyena, thanks to the curved mandible and (hint of) robust molars and shorter toothrow than you might expect to see in a canid. The broad and flat profile of the frontals between the eye sockets probably helped too:

Hyenas have an interesting evoloutionary history, branching off from the basal feliforms around 22 million years ago and adapting to fill a terrestrial carviore niche in Eurasia and becoming quite diverse. In America the canids were filling that same niche, which led to some competition when the canids made it to Eurasia (spoiler alert – the hyenas lost that competition, leaving us with just three highly specialised bone crushers and the decidedly weird Aardwolf living today).

The mystery specimen was labelled as Thalassictis wongii (Zdansky, 1924), a species described from China and originally placed in the genus Icititherium, but reassessed by Kurtén (1985). A cladistic treatment of the Hyaenidae by Werdelin & Solunias (1991) later placed it in the genus Hyaenotherium, but that may not have been accepted by the curatorial team in Oslo without an accompanying formal taxonomic treatment.

These are the sorts of decisions that need to be made when considering something as simple as a label stating a species name, so you can imagine my sense of trepidation as we are about to embark on a major project at the Dead Zoo, which will allow us to reassess the information with our 10,000 or so display specimens. Fun times ahead!

This week I have a mystery object for you from a recent visit to Oslo:

I apologise for the poor image quality – I was using my phone and this specimen was behind glass, so it was tricky getting a decent photo without a lot of reflections. Given the poor images I’ll drop in a clue – this is a fossil specimen from around 6 million years ago.

Any thoughts on what it could be? As ever, you can leave a comment down below. Have fun working this one out!

Last week I gave you this genuine mystery object to identify, from the collections of the Dead Zoo:

As you may have noticed, there is a preliminary identification with the specimen, that lists it as being an unidentified bird humerus from peat at Lough Gur in County Limerick. It’s dated to the Holocene, so nothing that you wouldn’t expect to find around today, at least within the wider European context.

I always maintain that identifications on labels should never be assumed to be accurate – although I’m happy to say that this one is correct.

The humerus is fairly large, which helps narrow down possibilities, but there are areas of damage on the articulations, where some useful features of the bone have been worn away, revealing the honeycomb texture inside the bone:

This sort of damage can often make identifications much more difficult, as it can remove diagnostic features and even change the profile of the bone, making it appear substantially different to the original form – especially where parts of elongated crests of bone have been lost:

When you attempt to identify a bone with this kind of damage, you have to keep in mind that something is missing, which can be very misleading when working from the overall shape. I think this is why many of you went down the route of a bird of prey, such as an eagle species or Osprey.

Generally in terms of an identification, the best option is to rule out the most likely species first – which means anything with a high population density or regular occurence, that frequents the habitat in which the bone was found. In this case my first thought went to waterfowl rather than raptor.

This humerus is too small for something like a swan or large species of goose, and too large for one of the ducks. However, it’s right in the range for one of the smaller goose species, so I took a look through some reference specimens from the genera Anser and Branta.

Of all comparisons, the Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis (Bechstein, 1803) was very close in size and shape, and where the shape differed it was where there was damage visible to the bone, making it likely that some of the features that seem to be missing were actually there originally but have been abraded away:

I’m still not 100% certain the mystery object is from a Barnacle Goose, but I’m quite confident that if it’s not, it’s from a close relative. I would love to hear your thoughts!

Last week we had these two skulls from Andy Taylor, FLS to have a go at identifying:

Everyone recognised that these are the skulls of Tube-nosed birds in the Order Procellariiformes – very large Tube-nosed birds.

Usually, you’d think of albatrosses when considering large Procellariiformes, but they have proportionally longer bills than this and while they have the nose-tube characteristic of the group, the tube is quite small and to the sides and rear half of the bill. In the mystery specimens, the tube is large and located on the top, and in the front half of the bill.

As Wouter van Gestel recognised, these skulls are from Giant Petrels in the Genus Macronectes. They actually represent both species in the Genus – the top one is the Southern Giant Petrel Macronectes giganteus (Gmelin, 1789) and the lower one is the Northern Giant Petrel Macronectes halli Mathews, 1912.

They’re quite hard to tell apart, and the best feature I noticed for distinguishing them is the shape of the palatine, with the Southern having a very gentle curve to the rear section – as indicated below (in a very rudimentary way):

Andy has already written up some information about these birds on his Instagram account, which is well worth checking out:

Thanks for all your observations and thoughts on these rather impressive specimens!

This week I have a guest mystery object – or two – for you to test your skills on:

I’d love to hear your thoughts on the identification of the skulls here – keeping in mind that any differences could be due to individual variation, sexual dimorphism or they may even be different species. Looking forward to hearing your thoughts!

Last week, I gave you this devilishly difficult genuine mystery object to have a go at identifying:

At first glance, it looks like it should be the occipital (the bone at the very back of the skull) of an Ostrich, or other very large bird. The bone is thin and dense (typical for a bird) and the overall shape and size looks like it might fit. However, none of the details of the bony sutures fit that possibility, for any large bird. Also, this came in as an enquiry, and was almost certaily found in Ireland, making a big bird even less likely,

With birds ruled out, I looked into the mammals. Generally it’s helpful to start with common species, to start ruling out the more frequently encountered species. There are some unfused sutures, so I began with looking at some common large mammals, keeping in mind the developmental differences that occur, making the skulls of juveniles appear quite different to adults of the same species. This is especially the case in relation to skull shape and presence of unfused sutures that can vanish in adults.

Sticking with the occipital, since the shape looks right and several people converged on the same idea (although the species suggested varied quite considerably), for me, the nuchal crest (the area of bone where the ligaments for the neck muscles attach to the back of the head) is very similar in shape to that of a sheep:

This would have been a nice and simple way to wrap things up, but unfortunately I’m still unsure. Mainly this is because the shape doesn’t match so well from other angles:

Of course, this may simply be an artefact of comparing a juvenile animal skull to an adult – so I’ll need to check with a range of specimens of different ages to be more certain.

However, there was also a suggestion of Porpoise (or other cetacean) by Adam Yates and Kat Edmonson came up with an intriguing suggestion that I am quite taken by. It is possible that the raised region is not the nuchal region at all (in Porpoises and many other cetaceans there’s actually a depression rather than a raised ridge in that area of the back of the skull), it may actually mark the junction between two very short nasal bones, a very compressed frontal region and the occipital at the back of a cetacean skull:

Just to help clarify, check out the area labelled 1, 2 and 3 in the image below:

So it may be that I was looking at the bone upside down the whole time. I’ll need to do some more comparisons to narrow down species if that is what it is, but huge thanks to Kat for getting me to see this object from a new perspective!

This week I have a weird mystery object for you to have a go at identifying:

This is a specimen that I came across from a small selection of enquiries I inherited.

I’m still not 100% certain what it is, although I have my suspicions. I’d be keen to know what you think!

You can leave your suggestions in the comments section below – I’m looking forward to hearing your thoughts.

Last week I gave you this mystery object to have a go at identifying:

Not the prettiest object perhaps, but I did find it in the gutter on my street, so I think that’s excusable.

This isn’t the most difficult specimen to identify – in fact, I think pretty much everyone should be familiar with it, since it’s probably one of the most commonly found bones in the world.

Chris was the first reply, within 23 minutes of the blog being posted. I was lucky enough to see Chris in Oxford this week, and he confirmed that most of that time was spent coming up with a suitable cryptic clue. And it was a spot on:

Foul! You should of cleaned it first, Paulo (although it is quite funny!)

Chris says: September 1, 2023 at 8:23am

As Chris hinted, this is of course the humerus of a Chicken Gallus domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758).

As I mentioned, this is probably the single most commonly encountered bone you’ll find. There are an estimated 34 billion Chickens alive at any given time, with around 74 billion being slaughtered for food each year, so it’s no surprise that their leg and wing bones accumulate wherever you find people.

In fact, the presence of a high density of Chicken bones in sediments is considered to be one of the features that will help to define the Anthropocene period.

The high density bit is important, since the Red Jungle Fowl has been around for 4-6 million years in Asia at low densities, but with the domestication taking place over 3,500 years ago, Chickens have travelled the globe with Humans, providing eggs and meat for a huge range of cultures.

But it’s not until huge numbers started being reared commercially in the 20th Century that landfills started containing vast numbers of bones from these birds.

Alongside a variety of other materials generated by human activity, from soot to radiactive isotopes dispersed around the globe by nuclear testing, chicken bones are providing a diagnostic features for geologists of the future to recognise the start of the Anthropocene.

So, bravo to Chris, and be sure to remember what this bone looks like, as I’m sure you’ll see plenty of them in future!

Last week we had a very difficult guest mystery object (or objects, as there were two specimens). These are from the collections of Andy Taylor, FLS:

The general consensus in the comments was that they are a type of mollusc, and due to the elongated nature there were a few suggestions of something in the Razor Clam area of the crunchy-yet-squishy zone of the tree of life.

But these are a bit more unusual than that, and unfortunately nobody seems to have picked up on my ever so cryptic clue:

You may need to delve into the depths of the internet to work it out

This refers to the fact that this species is one of the denizens of the deepest parts of the world’s oceans.

This combined with the characteristically elongated shell shape does help to narrow it down, although it takes a lot of work – or a degree of familiarity to work it out.

Remarkably, Dennis C. Nieweg on LinkedIn did manage to figure it out to the previous generic name of Calyptogena, which is hugely impressive for such an unusual and generally unfamiliar specimen.

These are specimens of Abyssogena (was Calyptogena) phaseoliformis (Métivier, Okutani & Ohta, 1986). They are very deep living bivalves in the Order Venerida, that survive around deep-water vents and seeps in the Abyssal zone and which were first described when submersibles were developed that could sample at great depths – opening up a whole new realm of discovery.

The details provided by Andy are as follows:

First specimen is from the Japan Trench and was collected at a depth of 6347m in 1997 by ’Shinkai 6500’ DSV (Deep Submergence Vehicle) operated by JASTEC (Japan Agency for Marine and Earth Science).

This second specimen was collected from the Aluetian Trench at a depth of 4776m – 44949m in 1994. This specimen was collected by the ‘RV Sonne’ with a remote submersible and TVG (TV guided grab).

Andy Taylor, FLS on 17 Aug 2023

So these specimens represent some of the deepest living organsims on Earth, which we’ve only known about the existence of for about 40 years. That’s pretty cool in my book!