Last week I gave you a St Patrick’s themed mystery object in the form of this snake:

It was a really difficult ask – the skin is faded and the specimen has been chopped into several pieces, making identification very tricky. I did provide a clue with the location of where this specimen is from, to offer a little help in narrowing down the possibilities (it’s from Venezuela).

Unfortunately, as Adam Yates spotted, I managed to leave in another more obvious clue that I thought I’d removed – the name of the species, which appears in the photo of the full specimen. I cropped the image in WordPress, not realising that if you click on it the original uncropped image opens. Not my finest moment!

However, specimen identifications need to be taken with a pinch of salt until they’re verified, so let’s do that as best we can.

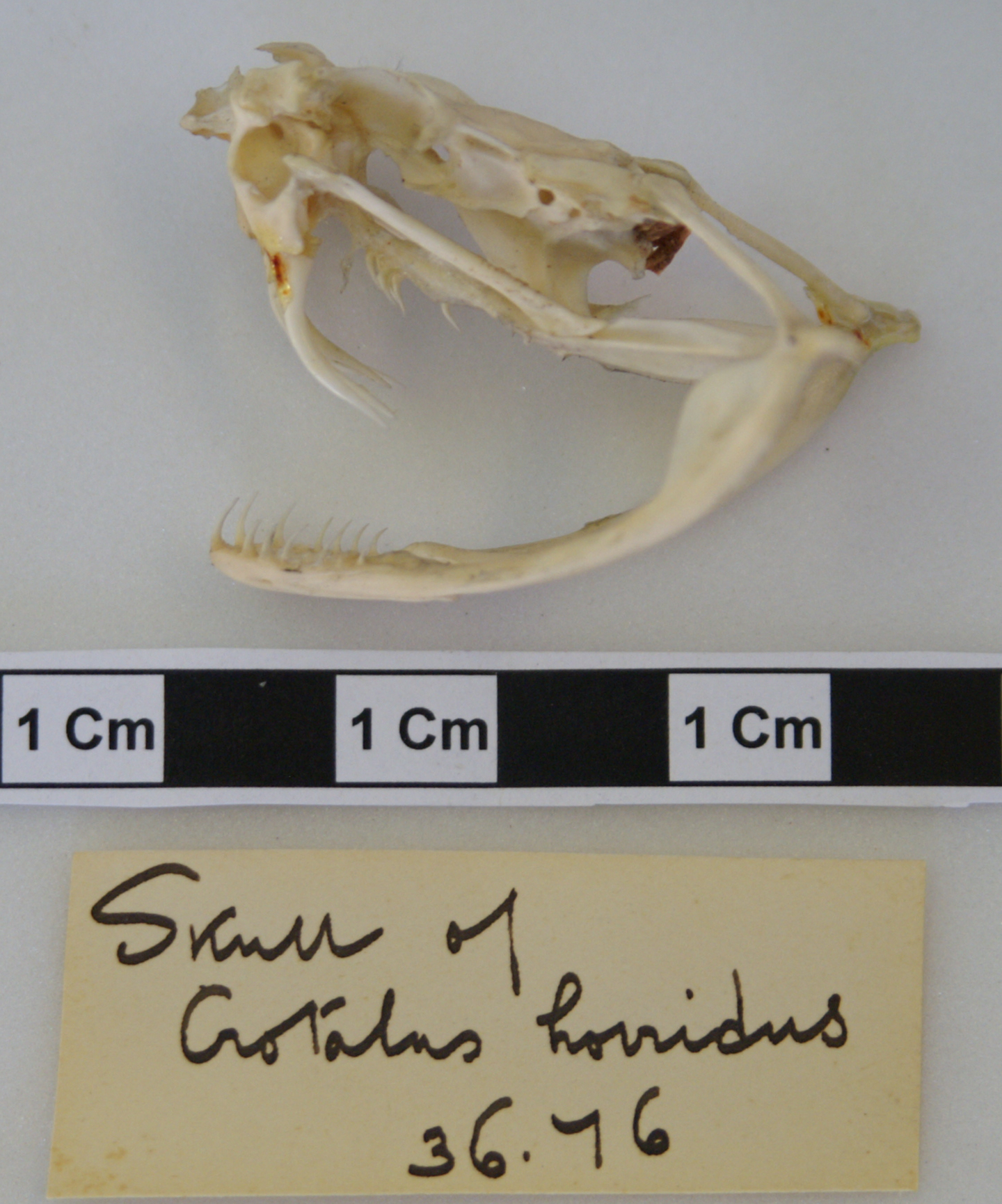

The side view of the head of this specimen gives a useful clue that Adam picked up on:

It has a sensory pit between the eye and the nostril, indicating that this is a type of Pit Viper, which does help reduce the options from around 50 Venezeulan snake species to around 15 or so. It’s also consistent with the identification of Bothrops venezuelensis Sandner-Montilla, 1952.

Most of the other Pit Vipers are fairly distinct from this specimen in terms of colour and pattern, but there are a couple of members of the Genus Bothrops (the Lanceheads) that are similar to this.

You may just be able to see a hint of a stripe behind the eye that terminates just above the last scale above the mouth, which can be useful in distinguishing between B. atrox (where the stripe touches the last three scales over the mouth) and B. asper (where it just touches that last scale as we see here), but this feature is less relaibe for B. venezuelensis, which can be distinguished from the other two species by having a more rounded rostrum:

This specimen’s rostrum (snout) is a little pointy, but for a type of snake called a Lancehead, you expect them to be very pointy. Of course this specimen is a little imperfectly prepared, so the rostrum shape may be misleading. As a result, I’d be a bit unwilling to differentiate between B. asper and B. venezuelensis based on the images.

What we do know is that this was certainly a venomous snake, since it bit a farm labourer working on a hacienda who required two doses of antivenom, but they thankfully survived. I suspect that this is why the head is separated, since the snake was killed and presumably identified to assist with administration to the appropriate antivenom.

This specimen is one of several from the same collector, who I plan to talk about more in future posts, since we have great information about a fascinating life.