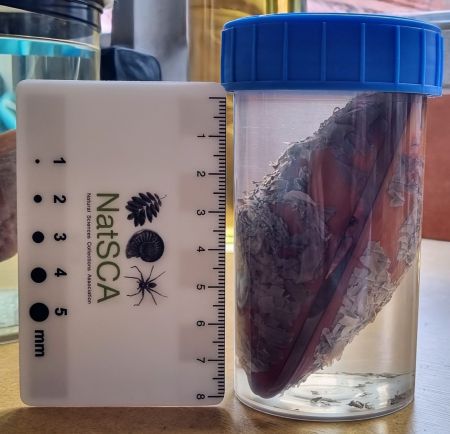

Last week I gave you a close up of a specimen from the Dead Zoo to have a go at identifying:

I don’t think this proved too much of a challenge, since Chris Jarvis responded with a correct identification within the hour:

This one’s sent me into a spiral, kudyu show a bit more,. bucky?

chrisjarvise8da89e10d says: July 18, 2025 at 8:44 am

In case you missed the cryptic clues here (after all, I suspect that not everyone is as much of an antelope aficionado as Chris), this is a male Greater Kudu Tragelaphus strepsiceros (Pallas, 1766).

These handsome, large, spiral-horned antelopes have a distinctive white chevron that runs between their eyes – presumably the clue that Chris spotted to identify this specimen so quickly.

There are other species in the Genus Tragelaphus that look similar to the Greater Kudu, but they have different colouration and subtly different patterns on their faces.

I had the photo of this specimen because I’ve been working with my colleagues in the National Museum of Ireland team on getting objects ready for display at another of our Dublin sites called Collins Barracks. Obviously this is one of those objects.

The Dead Zoo has been closed since last September, while we’ve been emptying the space of collections for a major and much needed refurbishment. Of course, we want to make some of the collection available to the public while the Dead Zoo is closed, hence the work we’re doing now.

However, the display we’re working on is a bit weird – but it’s not intended to be an exhibition. I want it to be more of an iterative experiment for myself and my team to work out how we’re going to deal with redisplaying and interpreting the collections when the refurbishment works are done and we reopen the main Dead Zoo building on Merrion Street.

We’re calling the temporary display the “Dead Zoo Lab”, because of the experimental approach we plan to take. We want to involve the public in a conversation about how what we’re doing works for our audiences. I’m excited to see how we can build dialogue in this space to help inform our work over the next few years.

I am getting a bit ahead of myself though, as we still need to finish installing objects over the next week or so, before we can open the doors to the public. Once we get to that stage I’ll be sure to share some photos of the space for the Zygoma community – and I’ll be excited to hear your thoughts!