Last week I gave you this mystery object to have a go at identifying:

This one is fairly straightforward to get to the superfamily level – it’s one of the Sea Turtles (the Chelonioidea). However, despite there only being seven species alive today, their skulls can take a bit of careful observation to distinguish the diagnostic features that offer the clues to a species level identification.

When attempting this kind of thing, it’s always helpful to have access to a good key or guide that illustrates and describes those diagnostic features, and for me a very useful resource is The Anatomy of Sea Turtles by Jeanette Wyneken. Alas this excellent reference only covers six of the seven species, so it’s worth also taking a look at the Chatterji, Hutchinson and Jones redescription of the skull of the Australian flatback sea turtle for the sake of completeness.

In the comments on the mystery object this became something of a mix, with a variety of options being proposed. The first, from Adam Yates was actually the correct identification, but he then second-guessed himself.

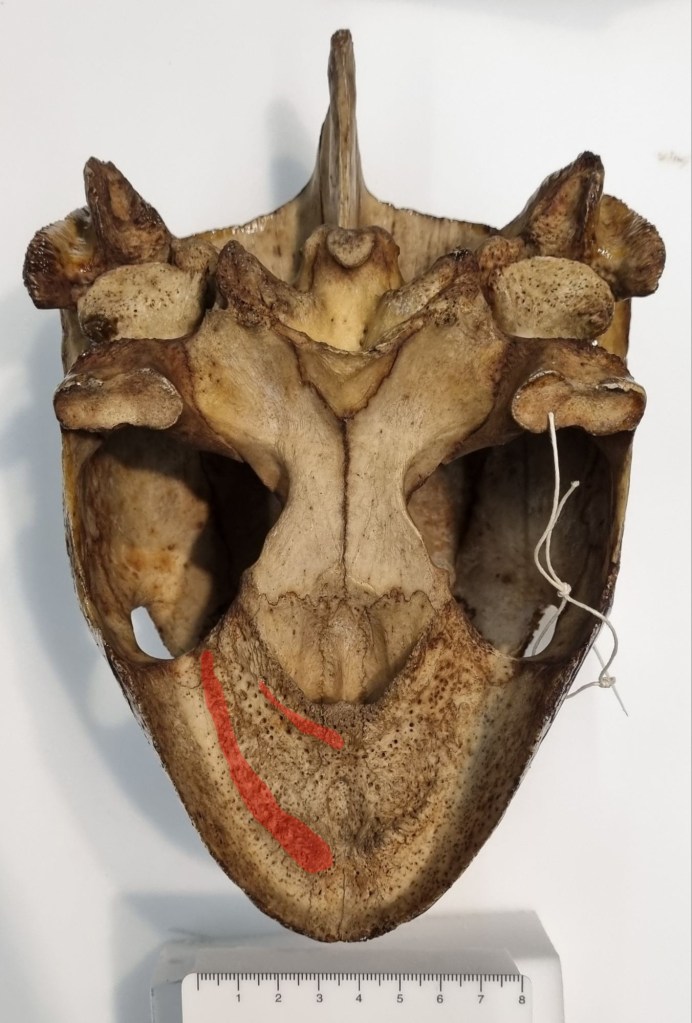

In a nutshell, you can tell that this is a Green Turtle, Chelonia mydas (Linnaeus, 1758) based on the broad U-shaped curve of the upper jaw (other Sea Turtles have a more pointed bill).

There are plenty of other features as well, such as the configuration of the bones of the palate, a pair of ridges in the maxilla – which are admitedly a little hard to make out, so I’ve indicated them in red below to help you spot where to look:

Another useful feature visible from the palate is the lack of pterygoid processes, which rules out the Australian Flatback Turtle.

I also happen to know that this specimen was collected from Ascencion Island, which is slap bang in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean and is renowned as an important breeding site for Green Turtles.

So thanks to everyone for your thoughts on this one – I hope you had fun investigating, and I hope you find the references above useful if you stumble across more turtle skulls in need of identification.

I should probably add that I picked this specimen because I spotted it during the install of some displays in the new Dead Zoo Lab, which I’ve been working on intensively for the last few weeks. This is a space where we will be displaying some of our collections, and working with collaborators and our audiences on how we’ll be using our objects in the future redisplay of the Dead Zoo when the building has been refurbished.

The Dead Zoo Lab is now open to the public, so I’ll add a photo of the space below, and you can read more about it in this article in the Irish Independent in case you’re interested. I hope you get to visit sometime – and if you do, be sure to let me know!