This week I have a piece of bone for you to have a go at identifying:

Just the one photo, so not much to go on, but I suspect you’ll be able to figure it out. Bonus points if you can work out where this bone was found. Have fun!

Last week I gave you this specimen from the Dead Zoo to have a go at identifying:

It didn’t take long for Chris Jarvis to drop a great clue to the correct answer, and it seems that overall it was a bit of an easy one for quite a few of you. I admit that I’m not overly surprised by that, since it’s pretty distinctive.

The scapula is long and curved, the humerus is relatively short and robust, the radius and ulna are robust and quite flattened, as are the digits on that wide and splayed-out hand. All of these elements add up to a flipper shape, but unlike the flipper of a cetacean or seal, it has quite short digits.

That’s because this is the left arm of a slow-moving aquatic mammal that plods along under the water (as much as plodding is possible whilst being underwater), rather than a hydrodynamic fast-swimming beastie with a flipper shaped to cut through the water.

There are still a few possible species that fall into this category, but of then all, there is only one with such a curved scapula shape – the Dugong Dugong dugon (Müller, 1776).

I picked this mystery object because it’s from one of several specimens that we’ve been working on recently, in preparation for transport out of the Dead Zoo, as we prepare for a major capital project on the building. The limbs, skull and tail were removed and the vertebrae and ribs stabilised in a structure that we call a “stillage”:

With enough wrapping and packing this specimen will be ready to crane out of the building in the near future, and it’s just one of several thousand specimens that will be making the move. If you’re interested in hearing more about the project, you can listen to an interview I did recently with Sean Moncrieff on NewsTalk.

I hope you enjoyed working out what this limb belonged to, and I suspect that there will be more tales (and possibly tails) from the decant coming up in future posts. Happy Friday!

Last week I gave you this specimen to identify, which came to me as an enquiry, after being found in the sea by a fisherman:

I don’t think it posed too much of a challenge, despite some damage, which has left sections looking a bit different to usual for this skeletal element – which is a section of the lower jaw or mandible.

This piece of the mandible includes the ramus (the rear part of the jaw behind the toothline where it rises up), coronoid process (the section of bone that rises up through the inside of the cheekbones, and where the temporalis muscles attach to power part of the action of the jaw) and the mandibular condyle (the hinging articulation point where the lower jaw meets the rest of the skull).

The scale bar shows that it’s fairly large, and the shape of the coronoid process and articular condyle are what I would consider to be quite distinctive to herbivores, since a long ramus isn’t well suited to resisting forces from struggling prey or meat-cutting bites.

From this point I find it’s useful to check an image I prepared earlier (and by earlier, I mean about 10 years ago):

A quick comparison makes it fairly clear that the mystery object is part of the mandible of a Cow Bos taurus Linnaeus, 1758, based mainly on the shape and orientation of the mandibular condyle.

There are of course species that could possibly turn up in Irish waters, that aren’t on my mandibles photo – in particular, Giant Deer, which Ireland seems to have a lot of. However, I have easy access to those specimens in the Dead Zoo and they have a similar mandibular condyle orientation to a Red Deer.

So well done to everyone who worked it out – I hope my explanation of the anatomy of the rear part of the mandible makes sense and maybe offers some pointers for identifications you might be faced with in the future!

Happy Friday everyone!

This week I have a mystery object for you that came in as an enquiry from a regular donor to the Dead Zoo’s collections. It was found by a fisherman in the Irish Sea, just off Howth, which is a lovely seaside village on a peninsula that marks the northern tip of Dublin Bay :

Any thoughts on what it might be? I suspect some of you will have a pretty good idea, so keep your suggestions cryptic if you can, so everyone has a chance to figure it out for themselves. I hope you have fun figuring it out!

Last week I gave you this genuine mystery object to identify, from the collections of the Dead Zoo:

As you may have noticed, there is a preliminary identification with the specimen, that lists it as being an unidentified bird humerus from peat at Lough Gur in County Limerick. It’s dated to the Holocene, so nothing that you wouldn’t expect to find around today, at least within the wider European context.

I always maintain that identifications on labels should never be assumed to be accurate – although I’m happy to say that this one is correct.

The humerus is fairly large, which helps narrow down possibilities, but there are areas of damage on the articulations, where some useful features of the bone have been worn away, revealing the honeycomb texture inside the bone:

This sort of damage can often make identifications much more difficult, as it can remove diagnostic features and even change the profile of the bone, making it appear substantially different to the original form – especially where parts of elongated crests of bone have been lost:

When you attempt to identify a bone with this kind of damage, you have to keep in mind that something is missing, which can be very misleading when working from the overall shape. I think this is why many of you went down the route of a bird of prey, such as an eagle species or Osprey.

Generally in terms of an identification, the best option is to rule out the most likely species first – which means anything with a high population density or regular occurence, that frequents the habitat in which the bone was found. In this case my first thought went to waterfowl rather than raptor.

This humerus is too small for something like a swan or large species of goose, and too large for one of the ducks. However, it’s right in the range for one of the smaller goose species, so I took a look through some reference specimens from the genera Anser and Branta.

Of all comparisons, the Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis (Bechstein, 1803) was very close in size and shape, and where the shape differed it was where there was damage visible to the bone, making it likely that some of the features that seem to be missing were actually there originally but have been abraded away:

I’m still not 100% certain the mystery object is from a Barnacle Goose, but I’m quite confident that if it’s not, it’s from a close relative. I would love to hear your thoughts!

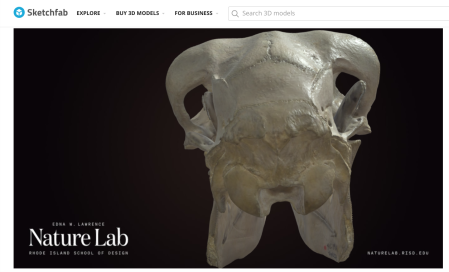

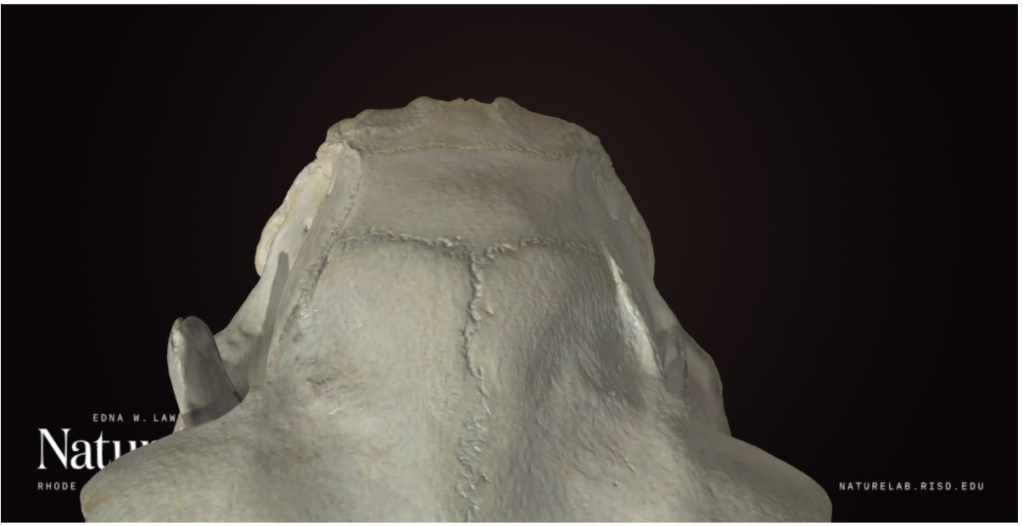

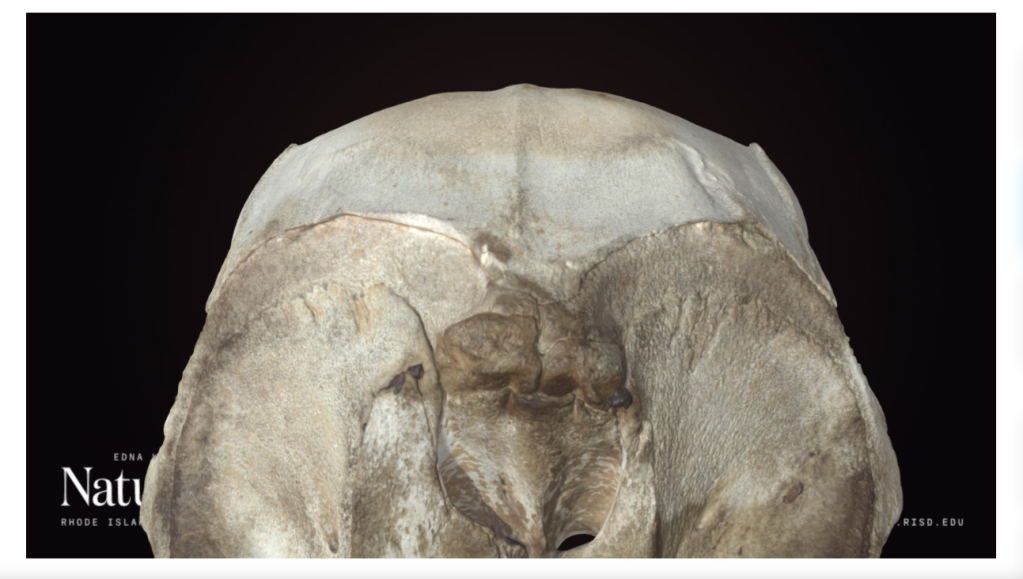

Last week, I gave you this devilishly difficult genuine mystery object to have a go at identifying:

At first glance, it looks like it should be the occipital (the bone at the very back of the skull) of an Ostrich, or other very large bird. The bone is thin and dense (typical for a bird) and the overall shape and size looks like it might fit. However, none of the details of the bony sutures fit that possibility, for any large bird. Also, this came in as an enquiry, and was almost certaily found in Ireland, making a big bird even less likely,

With birds ruled out, I looked into the mammals. Generally it’s helpful to start with common species, to start ruling out the more frequently encountered species. There are some unfused sutures, so I began with looking at some common large mammals, keeping in mind the developmental differences that occur, making the skulls of juveniles appear quite different to adults of the same species. This is especially the case in relation to skull shape and presence of unfused sutures that can vanish in adults.

Sticking with the occipital, since the shape looks right and several people converged on the same idea (although the species suggested varied quite considerably), for me, the nuchal crest (the area of bone where the ligaments for the neck muscles attach to the back of the head) is very similar in shape to that of a sheep:

This would have been a nice and simple way to wrap things up, but unfortunately I’m still unsure. Mainly this is because the shape doesn’t match so well from other angles:

Of course, this may simply be an artefact of comparing a juvenile animal skull to an adult – so I’ll need to check with a range of specimens of different ages to be more certain.

However, there was also a suggestion of Porpoise (or other cetacean) by Adam Yates and Kat Edmonson came up with an intriguing suggestion that I am quite taken by. It is possible that the raised region is not the nuchal region at all (in Porpoises and many other cetaceans there’s actually a depression rather than a raised ridge in that area of the back of the skull), it may actually mark the junction between two very short nasal bones, a very compressed frontal region and the occipital at the back of a cetacean skull:

Just to help clarify, check out the area labelled 1, 2 and 3 in the image below:

So it may be that I was looking at the bone upside down the whole time. I’ll need to do some more comparisons to narrow down species if that is what it is, but huge thanks to Kat for getting me to see this object from a new perspective!

This week I have a weird mystery object for you to have a go at identifying:

This is a specimen that I came across from a small selection of enquiries I inherited.

I’m still not 100% certain what it is, although I have my suspicions. I’d be keen to know what you think!

You can leave your suggestions in the comments section below – I’m looking forward to hearing your thoughts.

Last week I gave you this mystery object to have a go at identifying:

Not the prettiest object perhaps, but I did find it in the gutter on my street, so I think that’s excusable.

This isn’t the most difficult specimen to identify – in fact, I think pretty much everyone should be familiar with it, since it’s probably one of the most commonly found bones in the world.

Chris was the first reply, within 23 minutes of the blog being posted. I was lucky enough to see Chris in Oxford this week, and he confirmed that most of that time was spent coming up with a suitable cryptic clue. And it was a spot on:

Foul! You should of cleaned it first, Paulo (although it is quite funny!)

Chris says: September 1, 2023 at 8:23am

As Chris hinted, this is of course the humerus of a Chicken Gallus domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758).

As I mentioned, this is probably the single most commonly encountered bone you’ll find. There are an estimated 34 billion Chickens alive at any given time, with around 74 billion being slaughtered for food each year, so it’s no surprise that their leg and wing bones accumulate wherever you find people.

In fact, the presence of a high density of Chicken bones in sediments is considered to be one of the features that will help to define the Anthropocene period.

The high density bit is important, since the Red Jungle Fowl has been around for 4-6 million years in Asia at low densities, but with the domestication taking place over 3,500 years ago, Chickens have travelled the globe with Humans, providing eggs and meat for a huge range of cultures.

But it’s not until huge numbers started being reared commercially in the 20th Century that landfills started containing vast numbers of bones from these birds.

Alongside a variety of other materials generated by human activity, from soot to radiactive isotopes dispersed around the globe by nuclear testing, chicken bones are providing a diagnostic features for geologists of the future to recognise the start of the Anthropocene.

So, bravo to Chris, and be sure to remember what this bone looks like, as I’m sure you’ll see plenty of them in future!

Last week I gave you this genuine mystery object from Rohan Long, curator of the comparative anatomy collection of the Harry Brookes Allen Museum of Anatomy and Pathology at the University of Melbourne:

This specimen may have been collected by Frederic Wood Jones, a British comparative anatomist who headed up the Anatomy Department at the University of Melbourne in the 1930s. This may mean it could have come from almost anywhere, given Wood Jones’ links with other anatomists.

So all we really have to go on is the morphology of the object.

It’s clearly made from long section of quite highly vascularised bone:

It seems to be missing the smooth surface normally seen on bone, but that can be caused by a variety of factors, from disease and infection in the live animal to weathering after it’s been dead for a while.

The ends of the bone don’t have any indications of an articular surface:

The larger end has a bit of a hollow, but the smaller end appears to be broken and you can see a hollow core to the bone.

Overall, the shape is not really reminiscent of any long bone I can think of. It lacks a normal articular surface at the unbroken end and it has no crests or ridges that I would normally expect muscles to attach to. It tapers quite consistently and has a slight curve.

My first thought was shared by others in the comments, with Chris Jarvis getting in first with the simple but effective pun:

Oooh! Sick!

Chris Jarvis August 4, 2023 at 12:37 pm

This is of course a reference to Oosik, which is the name in Native Alaska Languages for the baculum or os penis of a Walrus Odobenus rosmarus (Linnaeus, 1758).

There are some differences between this specimen and some of the other Walrus bacula I’ve seen and which show up in an image search, but there are a variety of possible explanations for that.

One is simply that Walrus bacula are quite variable. They can vary significantly through the life of the animal as it develops, but it can also vary quite a lot between individuals. If you spend as long looking at Walrus penis bones on the internet as I have (what on Earth happened to my life?!) then you’ll notice that some have a strong double curve while others can be almost straight, others are thick and some are quite thin.

This variability is also seen in other pinnipeds with a high degree of sexual dimorphism, like Sealions and Elephant Seals.

So while it’s hard to be 100% certain of the identification, I think it is the most likely solution to this mystery.

I hope you had fun with this one!

This week I have a guest mystery object for you courtesy of Rohan Long, curator of the comparative anatomy collection of the Harry Brookes Allen Museum of Anatomy and Pathology at the University of Melbourne. Here’s some context about the collection from Rohan, it may help with an identification:

Our comparative anatomy collections date from the earliest 20th century and are predominantly native Australian mammals and domestic animal species. However, the academics at the University have always had international networks, and there are species represented in the collection from all over the world. Many have been prepared in a lab for class specimens, many have been collected in the field. The latter are assumed to have been associated with Frederic Wood Jones, a British anatomist with a fondness for comparative anatomy and island collecting trips who was head of our Anatomy Department from 1930 to 1937.

Do you have any ideas what this might be? As ever, you can leave your questions, insights and suggestions in the comments box below. Have fun with this one!

Last week I gave you a mystery object that came wrapped in this intriguing box:

The discovery inside was this:

Definitely not a Poptart.

This is a discovery made by 10 year old Anna, who found it when digging in the garden with her Dad, and she’s keen to know what it’s from. In fact, she’s hoping it’s from a new species of dinosaur, so it can be give the excellent name Annasaurus (although I believe such a creature already exists in the world of Doctor Who).

While the bone is pretty big, unfortunately it’s not from a dinosaur, but a large mammal. The cut surface looks very neat and that suggests that it’s been passed through a band-saw, probably by a butcher:

This would suggest it comes from one of the commonly eaten species, such as Sheep, Pig or Cow – although It is possible that butchered bone would come from another animal, such as Goat, Horse or a species of deer.

However, the size immediately reduces the likely suspects down a lot. It’s bigger than any Sheep or Goat bone I’ve encountered, so the focus is on Horse and Cow, although Red Deer and Pig are worth a look too,

Normally my first question is “which bone is it?” and in this instance it’s actually a bit harder than usual because it’s both cut and from a young animal, so the articular surface from the top of the bone (or epiphysis) hadn’t fused yet and is missing.

This means we’re looking at the neck section of the bone (the metaphysis), which is harder to find good material to compare against. However, with common species there are at least some excellent online resources to see full bones from a variety of angles that can help build up a picture of what to look for.

In this case I used OsteoID, which has good coverage of skeletal elements for a lot of mammal species that commonly occur in North America. I already recognised that this was from around the knee area, so I first checked if we are dealing with the leg section above the knee (distal femur) or the bit below (proximal tibia). Wouter van Gestel suggested shin bone (tibia) in the comments and I came around to that interpretation, so that’s what I originally went with.

However, Christian Meyer later suggested it was more likely to be distal part of the femur, and after looking at the specimen in hand, I find myself in agreement.

On to the species! It’s a good bit broader than the Pig femur (especially considering that the epiphysis is the broadest section of the bone and that’s missing here).

The shape of the metaphysis is too robust for deer, who have a more sharply defined ridge that runs into the main shaft of the bone (or diaphysis):

But it’s not as robust and it tapers more in the metaphyseal area than you’d expect from a Horse..

So after a good bit of comparison, I’m fairly certain that this is the distal metaphysis from the femur of a Cow Bos taurus Linnaeus, 1758.

I will write back to Anna to let her know about her discovery and while it may not be a dinosaur, it’s still an interesting find, so I hope she’s not too disappointed!

This week I have a great mystery object for you – it came in one of the best bits of post I’ve had for ages:

Here is the discovery that was inside:

Any idea what it might be?

As ever, you can leave your answers in the comments box below – but I suspect that some of you might know exactly what this is, so please try to keep your answers cryptic, so everyone has a chance to work it out for themselves. Have fun with it!

Last week I gave you a guest mystery object from Catherine McCarney, the manager of the Dissection Room at the UCD School of Veterinary Medicine:

The first question I normally try to answer when undertaking an identification is “what kind of bone is this?”, but in this instance it’s not immediately obvious.

There is a broad section with articulation points, a foramen (or at least something that looks like a hole, which might be a foramen) and a flattish section that looks like it probably butts up against something with a similar flat section. This would normally put me in mind of the ischium of a pelvis.

But it’s not a pelvis as the articulations are all wrong and the shape of the skinny piece of bone that projects off doesn’t fit any functional ilium shape that I’m aware of.

The pectoral girdle has a similar set of structural features and this object starts to make more sense with that in mind. Things like turtles and whales may have a structure like this, but there’s something to keep in mind: despite being fairly large, this object only weighed in at 26g.

Turtles and whales have dense bone that helps reduce buoyancy, to make remaining submerged less energetically demanding, but this bone must be full of air spaces – which offers a clue as to likely type of animal it came from. A bird – as Joe Vans noted in the comments.

Considering the size of this object there are very few possible candidates. Most birds are pretty small and this object is pretty big, so we just need to look at some of the Ratites.

The comparisons I managed to find have led me to the conclusion that this is most likely part of the pectoral girdle of an Ostrich Struthio camelus Linnaeus, 1758.

More specifically, I think it’s the coracoid (#2 on image), clavicle (#3 on image), and scapula (#4 on image) from the left hand side of the pectoral girdle of an Ostrich.

I was delighted to see that Wouter van Gestel agreed with this assessment in the comments, since he knows more about bird bones than I could ever hope to learn!

Finally I’d like to thank the fatastic Catherine McCarney for sharing this mystery object from the depths of the Vet School’s collections. I hope you all enjoyed this challenge!

I have a great guest mystery object for you this week. It comes from the wonderful Catherine McCarney, who is manager of the Dissection Room at the UCD School of Veterinary Medicine:

Here’s what Catherine has to say about it:

This object is a bone fragment from an unknown animal. It was discovered while cataloging an old box of historic specimens in the UCD School of Veterinary Medicine. It’s of limited use in the vet program, but my Zoologist background is keen on answering the mystery rather than simply discarding it. It has me stumped, it’s light weight (just 26g) had me thinking it must be from a bird, but some features are reptile like.

So, do you have any thoughts on what this mystery object might be?

As ever, you can leave your thoughts, questions and suggestions in the comments box below. Happy sleuthing!

Last week I gave you a somewhat challenging bony mystery object to have a go at identifying:

The first challenge is recognising the type of bone. It’s not part of the axial skeleton (like the skull, vertebrae, ribs, etc) and it’s not one of the long bones, which are very distinctive.bits of the appendicular skeleton (which includes the pelvis, shoulders and limbs).

So that leaves the distal bits of the limbs, which tend to be relatively small. This is where it helps to be familiar with bone shapes – and this sort of elongated rectangle with an articulation at just one end is fairly distinctively a heel bone or calcaneus. (N.B. the end without the articulation provides a connection point for the Achilles’ tendon.)

At 8cm it’s fairly large, so that suggests it’s from a fairly large animal. This actually confused me more than it probably should have – but more about that in a minute.

The calcaneus is a very functionally important piece of bone, so the shape will reflect the use. However, the use of a leg tends to be broadly similar between closely related animals. Therefore, while it’s fairly straightforward to rule out things like carnivores and primates by using online reference resources like the incredible helpful BoneID site, it all gets more complicated when you realise this is from a member of the Artiodactyla, which has 270 or so species.

Common species are a good place to start with comparisons, since you are more likely to find their bones. So I started by looking at Deer, Horse, Pig, Sheep and Goat. I probably got a bit sidetracked by the size of this particular specimen at first, but as I have maintained on many occasions, size can be misleading and shape is always a better factor upon which to base an identification, since animals of the same species can come in different sizes.

After ruling out Deer, Horse and Pig I found myself wavering between Sheep and Goat. To dig into the shape differences a bit more, I took a look at an interesting paper on geometric morphometric comparison between the calcanea of Sheep and Goats by Lloveras, et al. 2022. The shape is very similar between the two species, but the differences identified in that paper have me leaniing towards the idea that this mystery object is most likely the calcaneus of a Sheep Ovis aries Linnaeus, 1758.

The differences are quite hard to decribe in a non-technical way, in the paper it goes like this:

According to our results the shape differences across sheep and goat calcanea are mostly located on the calcaneal tuber and neck, the sustentacular tali region, the malleolus articular surface and the cubonavicular articular surface. In general terms, in sheep, the calcaneal tuber tends to be more concave on the anterior side and the calcaneum neck, the sustentacular tali region and the cubonavicular articular surface tend to be wider. In opposition, in goats, the malleolus articular surface region tends to be shorter and more prominent anteriorly. These morphological differences could reflect the functional adaptation of these animals in different habitats that demand different methods of locomotion. While the sheep is adapted to running across flat land, the goat is adapted to rocky escarpments.

Lloveras, et al. 2022

In general terms it’s probably sufficient to take a look at the specimens on BoneID (you’ll need to flip the mystery object in your head, as it’s upside down and a mirror image since it’s from the right leg rather than the left, which is what’s shown on the BoneID site). The angles and extent of the articulations seem to be better defined in Sheep and match more closely to the mystery object.

So congratulations to Adam, who was the first to figure it out (beating me to it, which led to some rapid back-pedalling by me in the comments!)

Finally, back to the size. All I can say is that the sheep that this calcaneus came from was, well, quite possibly memeworthy…