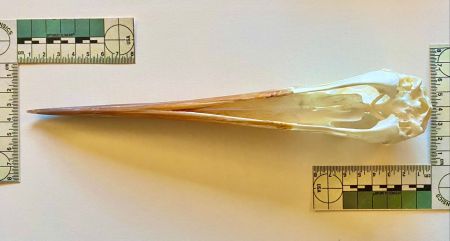

Last week I gave you this colourful chap to have a go at identifying:

As I mentioned in the previous mystery object answer, parrots can be hard to identify due to the large number of species globally. However, this time the specimen posed no problems for people to identify – perhaps unsurprisingly, given its importance.

Chris Jarvis was first in the door with the correct answer – a nice cryptic clue using the Seminole name for the species:

What a Puzz ila!

Other clues came thick and fast, but they all pointed to this yellow-headed, orange-faced bird being the now extinct Carolina Parakeet Conuropsis carolinensis (Linnaeus, 1758).

This colourful small parrot weighed in at around 100g and hung around in large flocks of up to 300 birds. Until the middle of the 19th Century they were commonplace in swampy forest habitats in parts of North America. The main resident population was in Florida although their range spread northwards along the marshes of the East coast (into the Carolinas) and westwards along the Gulf of Mexico just into Louisana.

A subspecies of the Carolina Parakeet (C. c. ludovicianus) also occurred in much of the Midwest and as far south as the top of Texas and as far north as the bottom of New York state. This subspecies had bodies that were more blue, but they disappeared alongside their greener sibling subspecies by the beginning of the 20th Century.

It seems likely that the usual culprits played a role in the extinction of North America’s only endemic parrot – habitat loss and overhunting. Swamps were drained and forests cleared to make way for agricultural land, the birds were then shot for feeding on crops, and their beautiful plumage made the birds a target to supply the feather-forward fashions of the time.

While most of the shooting stopped before the birds went extinct, as people started to recognise the risk of extinction (especially in the context of the Passenger Pigeon that was being eradicated at around the same time), the last small wild population was vulnerable and it has been suggested that they were finally wiped out by an avian disease.

While a few stragglers likely remained living wild in the Florida swamps until the 1930s, the last known Carolina Parakeet (a male named Incas) died in Cincinati Zoo in 1918, just four years after Martha (the last Passenger Pigeon) died in the very same cage. A somewhat dismal end to colourful species.