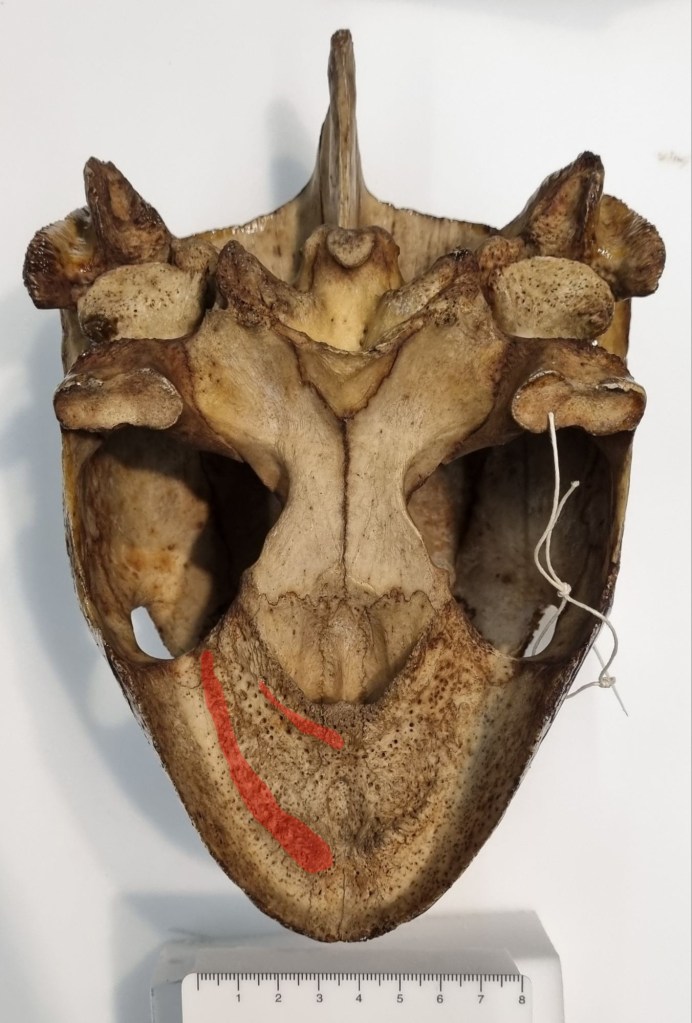

Last week I gave you the second of a series of bird pelvises to try your hand at identifying:

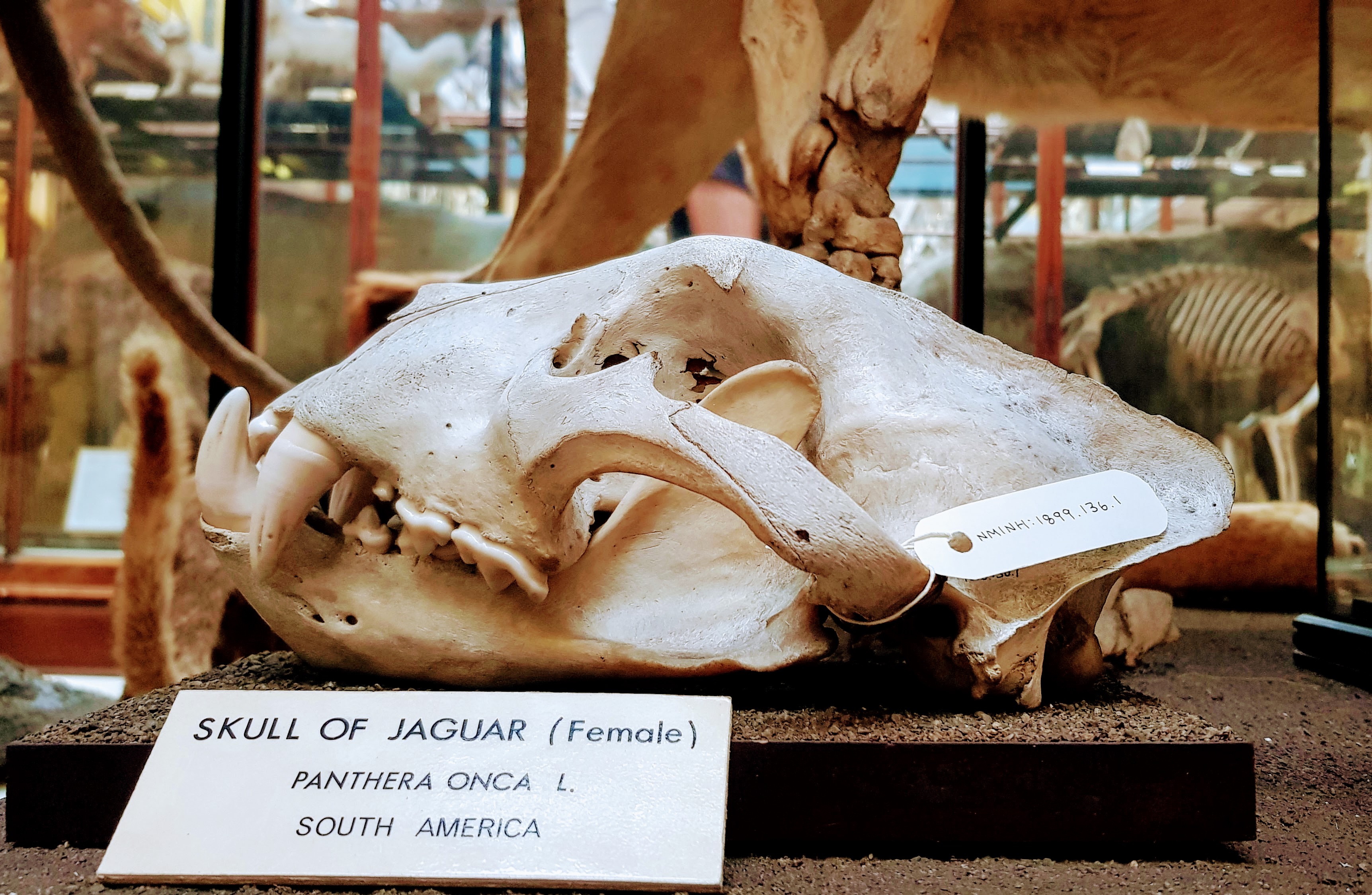

This one proved a bit more difficult than the previous example I offered up, which was from a Chicken – here’s that one for comparison:

As you can see, our mystery pelvis is a good bit smaller than that of the Chicken, and in terms of the shape, while it has some similarities, but it’s more compact and almost square. I’m not 100% sure why, but that makes me think of something that has a more upright body orientation than a Chicken.

Part of the reason it’s more square is that the areas of muscle attachment for the iliotrochantericus caudalis muscles (which I talked about a couple of weeks ago) don’t extend far forward, which suggests its femur isn’t being stabilised to enable a long stride. The attachment is quite wide though, so I suspect it may be optimised to cope with large forces in a burst instead.

There are a few species that would fit the bill (if you’ll excuse the pun) including Grouse – which was suggested by Chris Jarvis and it is remarkably similar – but this is the pelvis of a Rock Dove (in this case the domestic version) Columba livia Gmelin, JF, 1789 which was correctly spotted by Adam Yates.

I thought this one might be nice to use, as it lets me share a blast from the past that looks at the explosive take-off of a Pigeon, from Ben Garrod’s TV series Secrets of Bones, which I had the privilege to be scientific advisor for back in 2014. I hope you find the clip interesting!