This week I have a genuine mystery object for you from the collections of the Dead Zoo:

Any idea what this bone found in an Irish peat bog might be from?

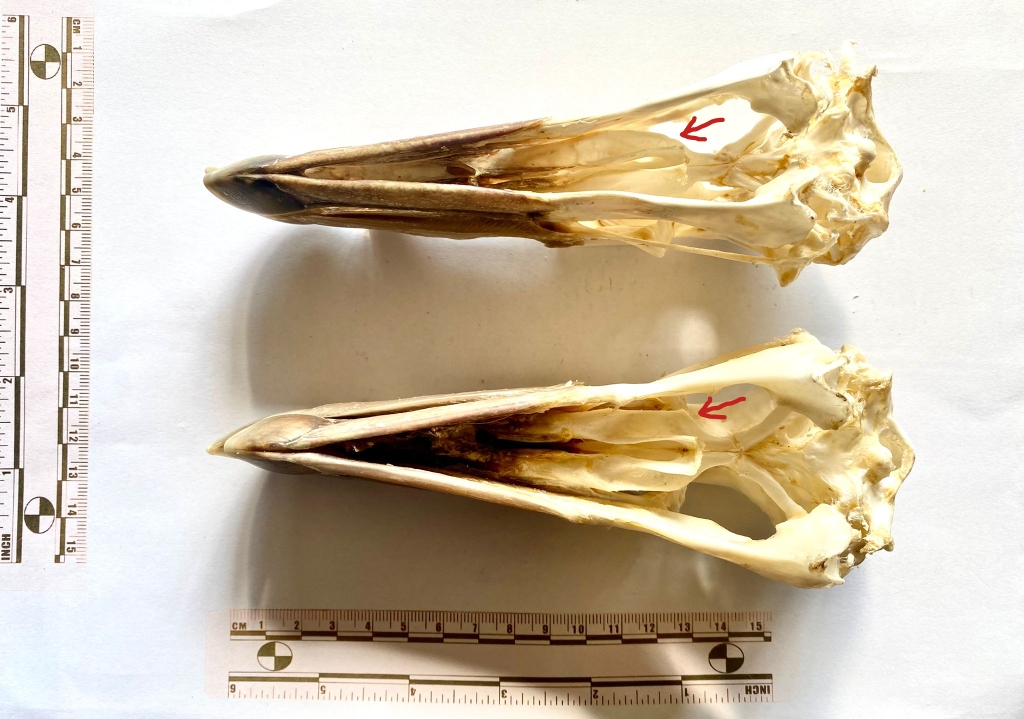

Last week we had these two skulls from Andy Taylor, FLS to have a go at identifying:

Everyone recognised that these are the skulls of Tube-nosed birds in the Order Procellariiformes – very large Tube-nosed birds.

Usually, you’d think of albatrosses when considering large Procellariiformes, but they have proportionally longer bills than this and while they have the nose-tube characteristic of the group, the tube is quite small and to the sides and rear half of the bill. In the mystery specimens, the tube is large and located on the top, and in the front half of the bill.

As Wouter van Gestel recognised, these skulls are from Giant Petrels in the Genus Macronectes. They actually represent both species in the Genus – the top one is the Southern Giant Petrel Macronectes giganteus (Gmelin, 1789) and the lower one is the Northern Giant Petrel Macronectes halli Mathews, 1912.

They’re quite hard to tell apart, and the best feature I noticed for distinguishing them is the shape of the palatine, with the Southern having a very gentle curve to the rear section – as indicated below (in a very rudimentary way):

Andy has already written up some information about these birds on his Instagram account, which is well worth checking out:

Thanks for all your observations and thoughts on these rather impressive specimens!

This week I have a guest mystery object – or two – for you to test your skills on:

I’d love to hear your thoughts on the identification of the skulls here – keeping in mind that any differences could be due to individual variation, sexual dimorphism or they may even be different species. Looking forward to hearing your thoughts!

Last week, I gave you this devilishly difficult genuine mystery object to have a go at identifying:

At first glance, it looks like it should be the occipital (the bone at the very back of the skull) of an Ostrich, or other very large bird. The bone is thin and dense (typical for a bird) and the overall shape and size looks like it might fit. However, none of the details of the bony sutures fit that possibility, for any large bird. Also, this came in as an enquiry, and was almost certaily found in Ireland, making a big bird even less likely,

With birds ruled out, I looked into the mammals. Generally it’s helpful to start with common species, to start ruling out the more frequently encountered species. There are some unfused sutures, so I began with looking at some common large mammals, keeping in mind the developmental differences that occur, making the skulls of juveniles appear quite different to adults of the same species. This is especially the case in relation to skull shape and presence of unfused sutures that can vanish in adults.

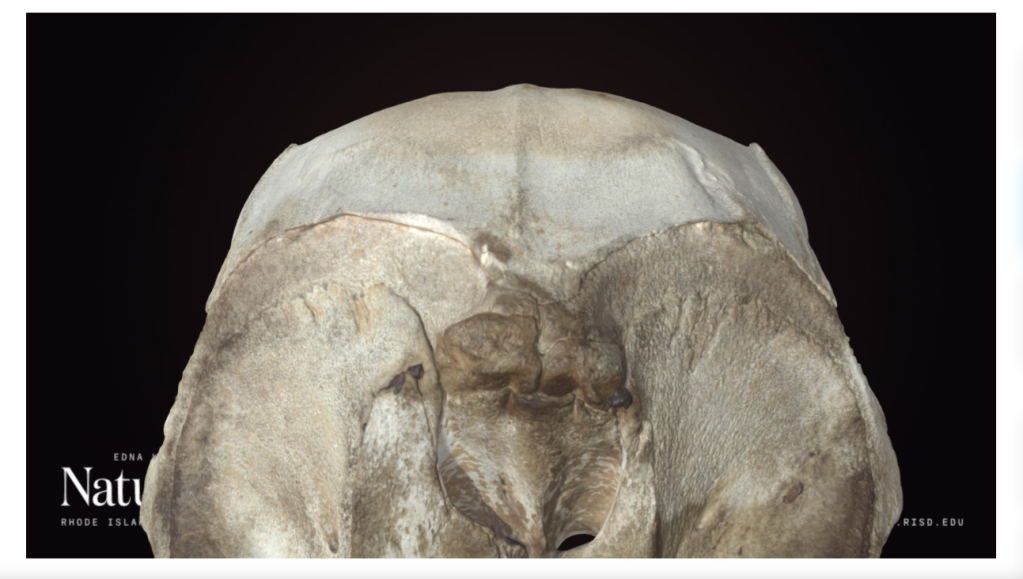

Sticking with the occipital, since the shape looks right and several people converged on the same idea (although the species suggested varied quite considerably), for me, the nuchal crest (the area of bone where the ligaments for the neck muscles attach to the back of the head) is very similar in shape to that of a sheep:

This would have been a nice and simple way to wrap things up, but unfortunately I’m still unsure. Mainly this is because the shape doesn’t match so well from other angles:

Of course, this may simply be an artefact of comparing a juvenile animal skull to an adult – so I’ll need to check with a range of specimens of different ages to be more certain.

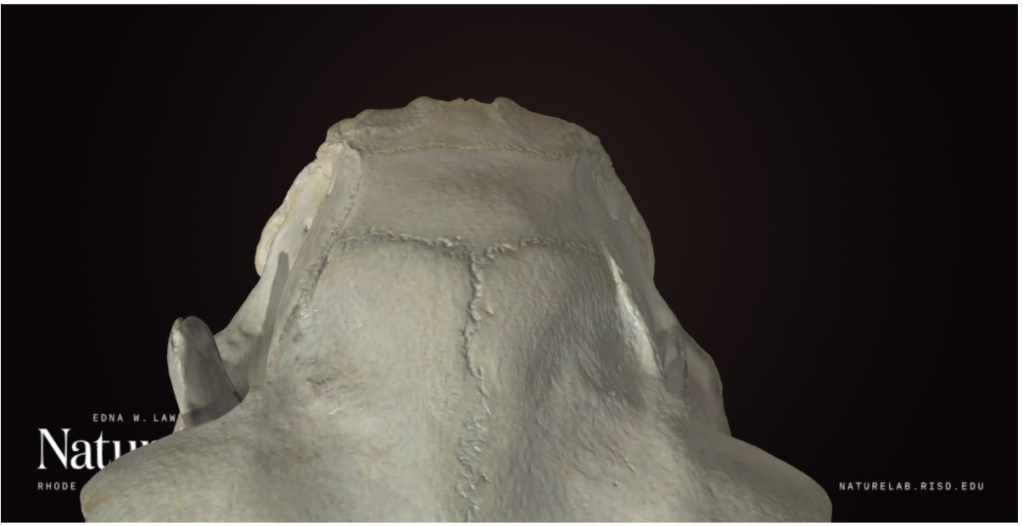

However, there was also a suggestion of Porpoise (or other cetacean) by Adam Yates and Kat Edmonson came up with an intriguing suggestion that I am quite taken by. It is possible that the raised region is not the nuchal region at all (in Porpoises and many other cetaceans there’s actually a depression rather than a raised ridge in that area of the back of the skull), it may actually mark the junction between two very short nasal bones, a very compressed frontal region and the occipital at the back of a cetacean skull:

Just to help clarify, check out the area labelled 1, 2 and 3 in the image below:

So it may be that I was looking at the bone upside down the whole time. I’ll need to do some more comparisons to narrow down species if that is what it is, but huge thanks to Kat for getting me to see this object from a new perspective!

This week I have a weird mystery object for you to have a go at identifying:

This is a specimen that I came across from a small selection of enquiries I inherited.

I’m still not 100% certain what it is, although I have my suspicions. I’d be keen to know what you think!

You can leave your suggestions in the comments section below – I’m looking forward to hearing your thoughts.

Last week I gave you this mystery object to have a go at identifying:

Not the prettiest object perhaps, but I did find it in the gutter on my street, so I think that’s excusable.

This isn’t the most difficult specimen to identify – in fact, I think pretty much everyone should be familiar with it, since it’s probably one of the most commonly found bones in the world.

Chris was the first reply, within 23 minutes of the blog being posted. I was lucky enough to see Chris in Oxford this week, and he confirmed that most of that time was spent coming up with a suitable cryptic clue. And it was a spot on:

Foul! You should of cleaned it first, Paulo (although it is quite funny!)

Chris says: September 1, 2023 at 8:23am

As Chris hinted, this is of course the humerus of a Chicken Gallus domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758).

As I mentioned, this is probably the single most commonly encountered bone you’ll find. There are an estimated 34 billion Chickens alive at any given time, with around 74 billion being slaughtered for food each year, so it’s no surprise that their leg and wing bones accumulate wherever you find people.

In fact, the presence of a high density of Chicken bones in sediments is considered to be one of the features that will help to define the Anthropocene period.

The high density bit is important, since the Red Jungle Fowl has been around for 4-6 million years in Asia at low densities, but with the domestication taking place over 3,500 years ago, Chickens have travelled the globe with Humans, providing eggs and meat for a huge range of cultures.

But it’s not until huge numbers started being reared commercially in the 20th Century that landfills started containing vast numbers of bones from these birds.

Alongside a variety of other materials generated by human activity, from soot to radiactive isotopes dispersed around the globe by nuclear testing, chicken bones are providing a diagnostic features for geologists of the future to recognise the start of the Anthropocene.

So, bravo to Chris, and be sure to remember what this bone looks like, as I’m sure you’ll see plenty of them in future!

Last week we had a very difficult guest mystery object (or objects, as there were two specimens). These are from the collections of Andy Taylor, FLS:

The general consensus in the comments was that they are a type of mollusc, and due to the elongated nature there were a few suggestions of something in the Razor Clam area of the crunchy-yet-squishy zone of the tree of life.

But these are a bit more unusual than that, and unfortunately nobody seems to have picked up on my ever so cryptic clue:

You may need to delve into the depths of the internet to work it out

This refers to the fact that this species is one of the denizens of the deepest parts of the world’s oceans.

This combined with the characteristically elongated shell shape does help to narrow it down, although it takes a lot of work – or a degree of familiarity to work it out.

Remarkably, Dennis C. Nieweg on LinkedIn did manage to figure it out to the previous generic name of Calyptogena, which is hugely impressive for such an unusual and generally unfamiliar specimen.

These are specimens of Abyssogena (was Calyptogena) phaseoliformis (Métivier, Okutani & Ohta, 1986). They are very deep living bivalves in the Order Venerida, that survive around deep-water vents and seeps in the Abyssal zone and which were first described when submersibles were developed that could sample at great depths – opening up a whole new realm of discovery.

The details provided by Andy are as follows:

First specimen is from the Japan Trench and was collected at a depth of 6347m in 1997 by ’Shinkai 6500’ DSV (Deep Submergence Vehicle) operated by JASTEC (Japan Agency for Marine and Earth Science).

This second specimen was collected from the Aluetian Trench at a depth of 4776m – 44949m in 1994. This specimen was collected by the ‘RV Sonne’ with a remote submersible and TVG (TV guided grab).

Andy Taylor, FLS on 17 Aug 2023

So these specimens represent some of the deepest living organsims on Earth, which we’ve only known about the existence of for about 40 years. That’s pretty cool in my book!

This week I have a pretty awesome guest mystery object from the collections of Andy Taylor, FLS. In fact, Andy has generously provided two, although they are examples of the same species:

Do you have any idea which species that might be? You may need to delve into the depths of the internet to work it out, but it’ll be worth the effort. Have fun!

Last week I gave you this genuine mystery object from Rohan Long, curator of the comparative anatomy collection of the Harry Brookes Allen Museum of Anatomy and Pathology at the University of Melbourne:

This specimen may have been collected by Frederic Wood Jones, a British comparative anatomist who headed up the Anatomy Department at the University of Melbourne in the 1930s. This may mean it could have come from almost anywhere, given Wood Jones’ links with other anatomists.

So all we really have to go on is the morphology of the object.

It’s clearly made from long section of quite highly vascularised bone:

It seems to be missing the smooth surface normally seen on bone, but that can be caused by a variety of factors, from disease and infection in the live animal to weathering after it’s been dead for a while.

The ends of the bone don’t have any indications of an articular surface:

The larger end has a bit of a hollow, but the smaller end appears to be broken and you can see a hollow core to the bone.

Overall, the shape is not really reminiscent of any long bone I can think of. It lacks a normal articular surface at the unbroken end and it has no crests or ridges that I would normally expect muscles to attach to. It tapers quite consistently and has a slight curve.

My first thought was shared by others in the comments, with Chris Jarvis getting in first with the simple but effective pun:

Oooh! Sick!

Chris Jarvis August 4, 2023 at 12:37 pm

This is of course a reference to Oosik, which is the name in Native Alaska Languages for the baculum or os penis of a Walrus Odobenus rosmarus (Linnaeus, 1758).

There are some differences between this specimen and some of the other Walrus bacula I’ve seen and which show up in an image search, but there are a variety of possible explanations for that.

One is simply that Walrus bacula are quite variable. They can vary significantly through the life of the animal as it develops, but it can also vary quite a lot between individuals. If you spend as long looking at Walrus penis bones on the internet as I have (what on Earth happened to my life?!) then you’ll notice that some have a strong double curve while others can be almost straight, others are thick and some are quite thin.

This variability is also seen in other pinnipeds with a high degree of sexual dimorphism, like Sealions and Elephant Seals.

So while it’s hard to be 100% certain of the identification, I think it is the most likely solution to this mystery.

I hope you had fun with this one!

This week I have a guest mystery object for you courtesy of Rohan Long, curator of the comparative anatomy collection of the Harry Brookes Allen Museum of Anatomy and Pathology at the University of Melbourne. Here’s some context about the collection from Rohan, it may help with an identification:

Our comparative anatomy collections date from the earliest 20th century and are predominantly native Australian mammals and domestic animal species. However, the academics at the University have always had international networks, and there are species represented in the collection from all over the world. Many have been prepared in a lab for class specimens, many have been collected in the field. The latter are assumed to have been associated with Frederic Wood Jones, a British anatomist with a fondness for comparative anatomy and island collecting trips who was head of our Anatomy Department from 1930 to 1937.

Do you have any ideas what this might be? As ever, you can leave your questions, insights and suggestions in the comments box below. Have fun with this one!

Last week I gave you an entomological mystery to solve, in the triangular(ish) shape of this moth:

For the real insect aficionados out there, this probably wasn’t too much of a challenge (I’m looking at you Tim), but for the rest of us it wasn’t quite so easy.

The overall appearance of this moth, with its size, shape (especially wing position), and fuzzy wing fringes is what you expect from a member of the family Noctuidae – the Owlet Moths. However, it’s a big family, with almost 12,000 species. A lot of the species also look similar to each other and some have a wide variety of different colour morphs – just to make things more complicated.

Context helps us out here, since although there are of lot of Noctuidae species in the world, there are far fewer found in Ireland and there are helpful resources that illustrate them.

Even with helpful visual resources, with good photos of the different Irish species, it can be hard to work out what the diagnostic features might be. For some species of moths you have to get into the fine detail of the genitals, but thankfully there are wing patterns that are distinctive in this instance.

In this case, the wing pattern of interest is the small triangular black mark on the lower portion of the leading edge of the upper wing.

That’s it.

The rest of the colour and pattern of the upper wing is very variable in this species, so you can’t rely on any of those features as a reliable indicator. Of course, if the specimen was alive and had its wings open, it would be a much easier identification:

This is, of course, a Large Yellow Underwing Noctua pronuba (Linnaeus, 1758), which is pretty obvious once the underwing is visible. So well done to everyone who worked it out from just the upper wings.

This week’s mystery object was found in the Dead Zoo, but not in the collections. I came across this specimen on the stairs on my way into work this morning:

Any idea which species this might be?

Probably a bit on the easy side for the entomologically inclined amongst you, so maybe keep your answers cryptic if you can.

Have fun!

Last week I gave you this really difficult, but incredibly cool mystery object to identify:

Definitely not a simple one for the uninitiated, but most of you got impressively close.

It looks a bit like ancient chewed gum at first glance (hey, it’s a thing!):

However, on closer inspection, some of the features start to emerge – including teeth:

Obviously, this is the fossilised skull or some critter, but what kind of critter is harder to determine.

The length suggests it’s something about the size of a rabbit:

And if you’re looking for a good fossil rabbit, you can’t beat Palaeolagus:

As you can see, the mystery object has a few differences, but due to the various missing parts, it’s a little hard to be confident exactly how different they are – although the shape of the orbital margin (the front of the eyesocket) gives a bit of a hint.

But, even more useful, is the curve in the maxilla (the upper jaw bone) that traces the root of the first incisor. In lagomorphs (rabbits, hares and even pikas), the incisor roots terminate with quite a big gap before the orbital margin, often with a triangular fenestrated region of cancellous bone (a sort of window of bony struts) in between.

The mystery specimen doesn’t have that – in fact the end of the incisor root is very close to the orbital margin. This is something you see in rodents.

I would have been impressed if you got that far, since the overall shape and size of this specimen definitely gives off a rabbity vibe, but believe it or not, this a dormouse. More specifically, it’s the Gigantic Dormouse Leithia miletensis (Adams, 1863) or if you want to go with the commonly used and more technically accurate, but nomenculatorily incorrect, L. melitensis, since Adams made a spelling error in his original description.

In fact, this is one of the specimens collected and figured by Adams in that original work describing the species, making this part of the type series for the species (although the holotype is more likely to be a very well preserved half mandible from the same site).

The fact that this is a fairly large and intact part of the type series means that it is of great interest to researchers. The reason I had this specimen to hand for the mystery object, is because I was preparing it for a research loan to some of my old colleagues in UCL, where it’s being MicroCT scanned.

This research will help refine an understanding of the morphology of the Gigantic Dormouse and offer some clues to what happens on islands that leads to the development of giants, building on work that they’ve been doing on this fascinating species, which is an interesting read that you can find here (you may even recognise Fig. 1B).

Virtual Cranial Reconstruction of the Endemic Gigantic Dormouse Leithia melitensis (Rodentia, Gliridae) from Poggio Schinaldo, Sicily, By Jesse J. Hennekam , Victoria L. Herridge, Loïc Costeur, Carolina Di Patti, Philip G. Cox – CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=92037373

Last week I gave you a somewhat tricky object to identify:

It’s only about 14mm long, it’s hollow and it has a seam down either side:

These features seemed to raise more questions than answers for many of you – and I’m not surprised, since this really does require some experience with the object to identify it.

Fortunately, some of you clearly had the necessary experience. Chris Jarvis and Adam Yates and Kat Edmonson all chimed in with some very useful suggestions, observations and discussion.

It’s a tooth from a Mugger Crocodile Crocodylus palustris (Lesson, 1831), in fact, if you want to be specific, it’s a newly emerging tooth from the 3rd socket from the rear in the left maxillary row.

I really wasn’t expecting anyone to figure out the exact species, but I was impressed that several of you figured out it was from the genus Crocodylus rather than Alligator.

There isn’t much published on dental morphological characteristics of extant crocodilians – a point noted in the one paper I was able find that tried to figure out what’s going on with crocodile tooth shape – although this one would more or less match up to M12 in this figure from that paper.

So well done to everyone who figured out the crocodilian source of this mystery object!

Last week I gave you a mystery object that came wrapped in this intriguing box:

The discovery inside was this:

Definitely not a Poptart.

This is a discovery made by 10 year old Anna, who found it when digging in the garden with her Dad, and she’s keen to know what it’s from. In fact, she’s hoping it’s from a new species of dinosaur, so it can be give the excellent name Annasaurus (although I believe such a creature already exists in the world of Doctor Who).

While the bone is pretty big, unfortunately it’s not from a dinosaur, but a large mammal. The cut surface looks very neat and that suggests that it’s been passed through a band-saw, probably by a butcher:

This would suggest it comes from one of the commonly eaten species, such as Sheep, Pig or Cow – although It is possible that butchered bone would come from another animal, such as Goat, Horse or a species of deer.

However, the size immediately reduces the likely suspects down a lot. It’s bigger than any Sheep or Goat bone I’ve encountered, so the focus is on Horse and Cow, although Red Deer and Pig are worth a look too,

Normally my first question is “which bone is it?” and in this instance it’s actually a bit harder than usual because it’s both cut and from a young animal, so the articular surface from the top of the bone (or epiphysis) hadn’t fused yet and is missing.

This means we’re looking at the neck section of the bone (the metaphysis), which is harder to find good material to compare against. However, with common species there are at least some excellent online resources to see full bones from a variety of angles that can help build up a picture of what to look for.

In this case I used OsteoID, which has good coverage of skeletal elements for a lot of mammal species that commonly occur in North America. I already recognised that this was from around the knee area, so I first checked if we are dealing with the leg section above the knee (distal femur) or the bit below (proximal tibia). Wouter van Gestel suggested shin bone (tibia) in the comments and I came around to that interpretation, so that’s what I originally went with.

However, Christian Meyer later suggested it was more likely to be distal part of the femur, and after looking at the specimen in hand, I find myself in agreement.

On to the species! It’s a good bit broader than the Pig femur (especially considering that the epiphysis is the broadest section of the bone and that’s missing here).

The shape of the metaphysis is too robust for deer, who have a more sharply defined ridge that runs into the main shaft of the bone (or diaphysis):

But it’s not as robust and it tapers more in the metaphyseal area than you’d expect from a Horse..

So after a good bit of comparison, I’m fairly certain that this is the distal metaphysis from the femur of a Cow Bos taurus Linnaeus, 1758.

I will write back to Anna to let her know about her discovery and while it may not be a dinosaur, it’s still an interesting find, so I hope she’s not too disappointed!

This week I have a great mystery object for you – it came in one of the best bits of post I’ve had for ages:

Here is the discovery that was inside:

Any idea what it might be?

As ever, you can leave your answers in the comments box below – but I suspect that some of you might know exactly what this is, so please try to keep your answers cryptic, so everyone has a chance to work it out for themselves. Have fun with it!

Last week I gave you a guest mystery object from Catherine McCarney, the manager of the Dissection Room at the UCD School of Veterinary Medicine:

The first question I normally try to answer when undertaking an identification is “what kind of bone is this?”, but in this instance it’s not immediately obvious.

There is a broad section with articulation points, a foramen (or at least something that looks like a hole, which might be a foramen) and a flattish section that looks like it probably butts up against something with a similar flat section. This would normally put me in mind of the ischium of a pelvis.

But it’s not a pelvis as the articulations are all wrong and the shape of the skinny piece of bone that projects off doesn’t fit any functional ilium shape that I’m aware of.

The pectoral girdle has a similar set of structural features and this object starts to make more sense with that in mind. Things like turtles and whales may have a structure like this, but there’s something to keep in mind: despite being fairly large, this object only weighed in at 26g.

Turtles and whales have dense bone that helps reduce buoyancy, to make remaining submerged less energetically demanding, but this bone must be full of air spaces – which offers a clue as to likely type of animal it came from. A bird – as Joe Vans noted in the comments.

Considering the size of this object there are very few possible candidates. Most birds are pretty small and this object is pretty big, so we just need to look at some of the Ratites.

The comparisons I managed to find have led me to the conclusion that this is most likely part of the pectoral girdle of an Ostrich Struthio camelus Linnaeus, 1758.

More specifically, I think it’s the coracoid (#2 on image), clavicle (#3 on image), and scapula (#4 on image) from the left hand side of the pectoral girdle of an Ostrich.

I was delighted to see that Wouter van Gestel agreed with this assessment in the comments, since he knows more about bird bones than I could ever hope to learn!

Finally I’d like to thank the fatastic Catherine McCarney for sharing this mystery object from the depths of the Vet School’s collections. I hope you all enjoyed this challenge!