Are apes monkeys?

Martin Robbins wrote a fun piece in The Lay Scientist the other day on the incorrect use of the term monkeys to describe apes (triggered by an article by Graham Smith for the Daily Mail). In Martin’s words:

A great crime against pedantry is in progress and it’s time for someone to draw a line

So as a pedant with a professional interest in this issue I am taking my stand, to help ensure that a miscarriage of pedantic justice doesn’t occur.

Nested hierarchies

Apes are monkeys in the same way that monkeys are primates, humans are apes and I am a human – it’s called a nested hierarchy.

This means that all apes are monkeys, but not all monkeys are apes. Just as all humans are apes, but not all apes are human. By the same token, humans are all ape, contrary to the title of the otherwise rather good book 99% Ape: How Evolution Adds Up.

This nested hierarchical system is the mainstay of biological taxonomy – each individual fits in its species (with the possible exception of hybrids), each species in its genus, each genus in its family and so on. It’s how Linnaeus organised things back in the 1750’s and it works remarkably well. [EDIT it’s actually a bit more complex than that]

Why do nested hierarchies work in biology?

Linnaeus’ system works well in biology because species share varying degrees of similarity depending on when they branched off from a common ancestor. The groups with most shared characteristics can be clumped together. That’s a bit tricky to explain in a few words, so here’s a simple diagram:

Primate phylogeny adapted to show clades. Image adapted from handout used by Mr. Krauz (click image for link to source)

The groups that form after a branching event are called ‘clades’ and the members of the group can correctly be referred to by the name of any of the clades that they are part of. This is known as monophyly (which means one leaf).

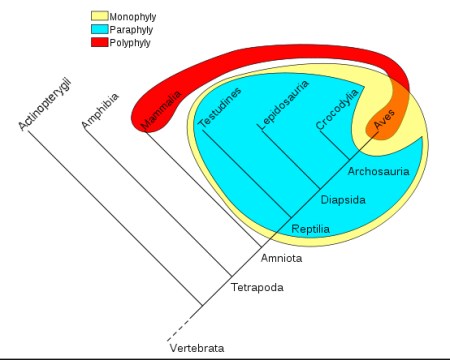

If a name is given to a group of species that are not all related in this way it will either be a polyphyletic group (many leaves) or a paraphyletic group (excluding leaves). Again, this can be confusing to describe, so here’s another diagram:

Polyphyletic and paraphyletic groups are not particularly scientifically informative, since they include or exclude members of clades with no evolutionary justification. This means that scientists prefer to base names for groups on clear monophyletic clades.

That’s a scientific argument for considering apes to be monkeys.

But ‘Monkey’ isn’t a scientific term

Aha! I must make it clear that I have been using the term monkey as a direct match for the term Simiiformes (which includes the Old and New World monkeys, the lesser apes and the great apes) in the discussion above, but is that valid?

Obviously I argue that it is, since I’ve been using it – the question should be why wouldn’t it be valid? The only logically robust answer (that I can think of) is that it wouldn’t be valid if people don’t commonly use the two terms to refer to the same things. So do people use the term monkey to refer to the apes?

The simple fact is that this whole discussion has been raised because Graham Smith published an article in which he refer to apes as monkeys, which demonstrates that monkey is indeed used as a generic term to refer to apes.

Another example is Terry Pratchett’s Discworld, where the Librarian (who happens to be an Orang-utan) dislikes being referred to as a monkey, which happens regularly – it may be fiction, but it seems reasonable to suggest that it reflects the use of terminology of real people.

In addition, I would suggest that it’s helpful for common terms for biological groups to directly reflect the scientific terminology as much as possible, since this improves the ability of scientists to communicate with a non-specialist audience. So even if monkey didn’t mean the same as Simiiformes (which it seems to) it probably should. Otherwise monkey has no scientifically meaningful analogue, since it would refer to a paraphyletic (and therefore arbitrary) grouping.

Case closed?

I think that my argument is pretty robust and I’ll stand by it until I hear something convincing enough to change my mind.

That said, I will add an important caveat – monkey is a generic term and when referring to Chimpanzees, Gorillas, Gibbons, Orang-utans and Humans the more specific term of ape should be used for clarity. After all, you don’t refer to your pet cat as a pet carnivore, or a budgie as a theropod, because generic terms omit a lot of additional information.

So although apes are monkeys, they are still apes – and that means something.

In the defence of the Librarian, I believe as a cataloguer of words, and someone who knows more than anyone else the powere words possess, and very specifically not as a scientist, he is defending (violently) the common definition of the word ‘monkey’ to mean a Simian with an external tail. It may not be a scientific term, but dammit, he’s proud to be able to manage just fine with the four limbs magic gave him.

Or uh, something.

Wholeheartedly agree Debi. Indeed the Librarian responds to the M word in much the same way as many people would respond to being referred to as an ape ….

What about Barbary macaques – they’re Simians that lack a tail, but they are in the same genus as several tailed monkeys…

Maybe they don’t exist on the Discworld.

Several tailed monkeys would certainly be a sight to see.

Lol – I should have phrased that better!

Thing is, “monkey” and “ape” are English words denoting two different sets of things. You might call a zebra an “equine,” but I doubt you generally call it a “horse.”

Actually, I would say that a Zebra is a horse, given that Eocene fossil equids are referred to as horses and thus the horse clade would certainly encompass Zebra.

However, as I say in the post “That said, I will add an important caveat – monkey is a generic term and when referring to Chimpanzees, Gorillas, Gibbons, Orang-utans and Humans the more specific term of ape should be used for clarity” So more generic terms are only appropriate under certain conditions of reference.

No, while Zebras and Horses are both under Equus, and closely resemble each other, they are two different species.

It’s pretty common to refer to zebras as horses in striped pyjamas, so, yeah, zebras are horses in common usage.

🐜

I guess this debate is exclusive to the English language : in French we don’t have a word for “apes”. We just call them “great monkeys” (Grands Singes).

I think monkey came into English from the Germanic influence – in fact the etymology that I’ve found has the following:

at Etymology Online.

Interesting to note that Monkey was the son of Martin the Ape.

Fascinating. (sorry for replying so late – I just got reminded of this article because I keep getting notifications whenever a new comment is posted.) So that would be the second (to my knowledge) animal noun derived from the name of a character in the Roman de Renart. The first, of course, being the French word “renard” who means “fox”, and replaced the ancient word “goupil” (from latin “vulpes”) who was used before.

that is a biologically incorrect moniker

Unless you call all monkeys great, that sounds a lot like a name for apes.

Pingback: Apes are monkeys, sea reptiles, and squares. Oh my! | blogowhat

I’m still reeling from the discovery there’s a new Planet of the Apes movie.

I must admit that I’m positively underwhelmed from what I’ve seen on the trailer…

It seems to me that the problem with arguing that non-scientific words such as “monkey” can’t be paraphyletic is that it means birds are reptiles, and that mammals are fish… and I’m not sure many non-scientists would agree that they are. So there’s clearly precedent for paraphyletic words in common usage. That doesn’t necessarily mean that monkey has to be paraphyletic too, of course, but I note that the Concise OED defines the word ‘monkey’ as meaning “a small to medium sized primate typically having a long tail … [Familes Cebidae and Callitrichidae (New World) and Cercipthecidae (Old World)]”. The technical accuracy and up-to-date taxonomy of that definition might be challenged, but its clear that they are referring to a paraphyletic assemblage that excludes apes. Dictionaries may be not absolutely prescriptive, but it does suggest that the paraphyletic meaning is a commonly accepted one by non-scientists.

Besides, we all know that the word means “£500″…

But birds are reptiles (if you want to use the horrible term ‘reptile’) and mammals are fish (although I prefer the more meaningful osteichthyes) – if a non-scientist disagrees that’s their prerogative, but they’re basically wrong and they shouldn’t kick up a fuss if someone does describe a bird as a reptile or a mammal as a fish.

I personally don’t use the term monkey when discussing apes, because ape is more meaningful. When discussing monkeys there may be an implicit exclusion of apes, but it is implicit. Plenty of people refer to apes as monkeys and therefore the implicit exclusion of the apes doesn’t justify the explicit censure of people using ‘monkey’ when discussing apes.

And you’re right, monkey does explicitly mean £500

Ok, so let’s just call everything fish, since we all evolved from fish… And we all evolved from microbes, so humans are microbes too. If I want to call humans microbes I can’t see how that would cause any confusion at all! Microbes were the first animals to use fire as a tool. Yeah makes sense…

We call monkeys monkeys because that’s a type of animal that is different than apes. They’re smaller, they have tails and they have different behaviors.

No, because “microbes” does not constitute a clade.

As to the whole “monkeys have tails” thing, you should probably read my follow-up post: https://paolov.wordpress.com/2011/04/24/tired-of-monkeying-around/

It’s rather presumptuous to declare common usage “basically wrong” simply because technical meanings used in a very specific way in specific fields arose centuries or millenia after the words themselves originated.

I pointed out to Martin Robbins that King Louie – an Orangutan – was famously “tired of monkeying around”. That’s good enough for me.

Perfect example! I am now singing King of the Swingers… thanks.

It’s always great to see a debate started about cladistics, so thanks for the post 🙂

I think where we differ is on the subject of what to call Simiiformes, the collection of Old and New World monkeys, and Apes. You think that group should be called ‘monkeys’, I think it makes more sense to call them ‘simians’. I’d argue that, cladistically-speaking, monkey is an obsolete term, but that’s my opinion and I’m not really aware of much of a consensus either way 🙂

As for the common usage argument, well I’m no great respecter of that 🙂 I completely agree that “it’s helpful for common terms for biological groups to directly reflect the scientific terminology as much as possible”, but that’s why I think it makes more sense to talk about simians, apes and Old and New World monkeys – we have a rich vocabulary of common terms to use here, so let’s use them to make the public more aware of the nuances of our family, rather than turning the whole group into a sort of single ‘monkey’ splodge.

I totally agree with respect to how terminology should probably be used, but the fact is that it isn’t necessarily used in that way and it’s somewhat unfair to censure someone for using a term that you disagree with, but for which there is plenty of reasonable justification for using.

With respect to Graham Smith’s article I think that the use of the term ‘monkey’ was a bit inappropriate given that the more informative term ‘ape’ was available, but that does not mean that he was actually wrong in his use of words. Your article (although very enjoyable) is actually more incorrect because you make an explicit statement of fact that apes are not monkeys, when it is not actually a fact at all – it’s an equivocal opinion. That for me is the actual issue here.

It’s been lots of fun though! 🙂

“Polyphyletic and paraphyletic groups are not particularly scientifically informative”<=Actually, they are.

If you are interested in the importance of bones in swimming: so you will study non-tetrapods osteichthyes (and cetaceans, penguins, pinnipeds, plesiosaurs…).

[]s,

Roberto Takata

That’s a very good point – I should have said taxonomically uninformative!

Pingback: links for 2011-04-21 « Thagomizer.net Thagomizer.net

AronRa on YouTube dealt with this subject ages ago – “Turns out we did come from Monkeys” – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4A-dMqEbSk8

Thanks Mintz – the video is brilliant and explains my rationale in far more detail than I managed here. Tempted to embed it in the post…

This is a really nice summary of why cladistics works. Well done!

For the dark-side version … read about baraminology.

Wow – that baraminology requires some crazy new kind of logic…

If “monkey” is the monophyletic term that includes old world monkeys, new world monkeys, gibbons AND apes, what is the paraphyletic term used to exclude apes? I’d always understood it (ignorantly, perhaps) as Martin put it; that “Simian” encompassed all monkeys, gibbons and apes, and “monkey” covered non-ape simians… Hair splitting of the best kind, great stuff 😀

Monkey is a monophyletic term that includes old world monkeys, new world monkeys, gibbons AND apes, rather that the monophyletic term.

Paraphyletic terms are taxonomically redundant, but in common usage I think that apes are excluded by some when talking about monkeys – but not by others.

My gripe is that you can’t say that someone is wrong for calling an ape a monkey, when there is perfectly good taxonomic support for doing so.

It is rather fun, although we seem to be getting a bit circular… 🙂

“I totally agree with respect to how terminology should probably be used”

Good grief, then we’re in agreement!

Trying to call simiiformes ‘monkeys’ in a scientific paper would, I suspect, get you smacked down by a lot of reviewers (certainly the biologists who’ve written to express their appreciation since the post went up!).

Using it as a common term is both wrong and confusing. It’s a science communication fail that basically says “primates are too complicated for your puny non-academic brain, so we’ll just pretend they’re all monkeys.” If the goal is to obfuscate our ancestry and stop people having to think about where we sit in the tree then great, but I don’t see it as a great approach!

But I suspect we’ll have to agree to violently disagree on this one 🙂 Still, it’s an interesting debate!

OK Martin, I’m happy to disagree in an entirely amicable and enjoyable way 🙂

However, I will say that you accused Graham Smith of being wrong, when actually he isn’t wrong – he just has a different opinion of the use of monkey than you. Moreover, there are perfectly sound reasons why his opinion (on the use of monkey) is valid, which I have provided some evidence for in my post.

If we agree to disagree after interrogating the evidence available, the only conclusion that can be drawn is that the use of monkey as a term that includes apes is equivocal. Which means that you are wrong when you assert in certain terms that apes should not be called monkeys.

Pingback: Tired of monkeying around « Zygoma

“Monkey” or “ape” are not “monophyletic terms”. Monophyly is needed for formal taxa, not for common terms like “fish”, “wasps”, ” or “monkeys”.

Simiiformes is a taxon, it is and must be monophyletic, and it includes monkeys, apes and humans.

Monkeys is not a taxon, it’s not monophyletic, and it doesn’t include apes or humans.

I don’t think we should impose the strict rules of taxonomy to common language. There is no need to “deal with it”.

Not sure if you read the follow-up post, but I address this issue. Common names do need to relate back to scientific taxonomy, otherwise a gulf opens in understanding.

If common language did not relate to taxonomy the public would still be happily calling whales ‘fish’. Dictionaries can be slow to incorporate findings from taxonomy, but it happens all the time. This means that the public lexicon changes in response to taxonomy. The fact is that taxonomy informs public understanding (albeit slowly) and there are good reasons for this to happen.

The perceived dichotomy between taxonomic science and common terms is false and I would argue that it is largely perpetuated by taxonomists who have lost sight of the fact that their work has real implications for how society can address biodiversity issues. Therefore there is a good argument for aligning common terms with taxonomic ones, to facilitate this process.

We as scientists should not assume that the public are stupid, ignorant or disinterested – we should be sharing our findings and those findings should be integrated into society. The ivory tower mentality is frankly bull and it should not be perpetuated, so I argue that there is a very real need to “deal with it”.

“If common language did not relate to taxonomy the public would still be happily calling whales ‘fish’.”

Ironically, you are asking them to call a whale a fish once again. I bet that won’t confuse anyone. 😉

😉 I guess I am to some extent, since whales are Osteichthyes (as indeed are apes), but I refer back to my closing caveat, where I make the point that it’s still best to use the most clade specific term when referring to something, in order to avoid confusion by over-inclusion.

I remember some debate about re-cycling the old paraphyletic groups (like Osteichthyes) or dropping them and erecting monophyletic groups with new and less confusing names (like “Ostei”)

“If common language did not relate to taxonomy the public would still be happily calling whales ‘fish’”

Of course common language did relate to taxonomy in many senses. I don’t deny it. And both realms influence mutually and evolve together. I think this evolution is going fine, so let’s not force it to the absurd end. At this moment, whales are not fish, but some people whant them to be fish again 😉 Perhaps in the future children will learn that whales are mammals and fish, vertebrates and invertebrates at the same time. And microbes 😉

How does one ‘force’ evolution of language to an ‘absurd’ end? Surely the most we can do is inform the evolution of language? More to the point, what’s ‘absurd’ about tweaking commonly used names for taxonomic groups so that they refer to their updated cladistic equivalents? This doesn’t seem absurd in the least – I’d be interested to hear why you think it is.

Great to discuss! 🙂

“what’s ‘absurd’ about tweaking commonly used names for taxonomic groups so that they refer to their updated cladistic equivalents?”

Well, I think it’s more complicated. “Monkey” is not a common name for a taxonomic group. It’s a common name without a taxonomic equivalent. Not every taxon name has a common version, and not every common name for animals or plants can be translated to a valid taxon. Sometimes a bit of tweaking is not enough, you need to make a big, sudden distortion of meaning, and start a campaign to spread it or impose it.

Why this is sometimes absurd? It’s hard for me to explain the absurdity, that’s why I tried (with irony) to express it with some extreme cases.

Consider “tree”. It’s polyphyletic but who cares? I think you’ll probably find it absurd if I try to distort the meaning of “tree” because I want to synonymize it with some monophyletic plant taxon.

It depends. My four year old daughter LOVES dinosaurs. So she asked what happened to dinosaurs and I said “they’re birds now. Birds are dinosaurs.” And, of course, they are. (Noting of course the feathered and quite possibly warm-blooded dinosaurs, and the birds with teeth … that’s why birds act like crazy lizards.)

‘“Monkey” is not a common name for a taxonomic group. It’s a common name without a taxonomic equivalent.’

Actually, given that ‘Monkey’ is used commonly used to describe the Old World Monkeys, the New World Monkeys and apes (check common usage – chimps, orangs, gorillas are all referred to as monkeys in numerous places) it means that ‘monkey’ is already used as a direct taxonomic equivalent for the Simiiformes. The people who disagree with this (Martin Robins for example) are the ones who are trying to apply the outdated taxonomy.

Now that is absurd.

“(…) it means that ‘monkey’ is already used as a direct taxonomic equivalent for the Simiiformes”

No, because common usage of “monkey” doesn’t include humans (despite some “campaign” efforts). You have a similar example with the wasps: nobody say wasp when seeing an ant. So wasp is not an equivalent of Hymenoptera or Apocrita. If you want to refer to the Apocrita, you have to say Apocrita, not “the wasps”.

“The people who disagree with this (Martin Robins for example) are the ones who are trying to apply the outdated taxonomy”

Maybe… But I like the modern taxonomy 🙂

As for the dinosaurs, David Gerard, the birds are classified as dinosaurs: they are members of the a clade with the formal name “Dinosauria”. This is real taxonomy. No problem at all.

I disagree, if the Rolling Stones, Pixies and Douglas Adams use the term monkey in relation to humans, I would say that the term was in common usage.

Will expand when I have the chance, but a bit busy for now.

I like the modern taxonomy too and I am not suggesting anywhere that it changes.

What I am suggesting is that since terms the term ‘monkey’ is already in general usage (within the non-taxonomic scientific community as well as by the public), usage should relate back to an appropriate taxonomic clade, in order to make the term clearly intelligible within the context of modern systematics.

For monkeys this is the Simiiformes, which includes the apes.

The point of this whole argument is that Martin Robbins wrote a post in which he says that apes aren’t monkeys. This statement is incorrect either if you go by common usage (since people often call apes monkeys) or if you go with any clade-based interpretation of monkeys that accommodates all taxa known as a monkeys (which is the Simiiformes). The only way in which Martin’s comments can be accurate is if traditional taxonomy is applied and a paraphyletic group that encompasses the monkeys is created.

If you don’t use traditional taxonomy, I find it hard to understand your disagreement with this. Unless you simply don’t like the idea of considering apes to be monkeys, which is your opinion, but I don’t see how it can be supported by common usage or cladistic arguments.

“For monkeys this is the Simiiformes, which includes the apes”

OK. Simiiformes = the monkeys. So, a neandertal is a monkey (because it’s one of the Simiiformes).

But let’s continue:

Hymenoptera = the wasps. Ants are wasps.

Equidae = the zebras. Donkeys are zebras.

Squamata = the lizards. Rattlesnakes are lizards

Vertebrata = fish. A vulture is a fish. Tyrannosaurus rex, awesome fish! Tell the children :o)

“Unless you simply don’t like the idea of considering apes to be monkeys, which is your opinion, but I don’t see how it can be supported by common usage or cladistic arguments.”

As you have probably noted, English is not my mother tongue. I don’t feel specially concerned about the monkey/ape distinction. There is no such distinction in Spanish or French, but some scientists and science writers are now making it, influenced by the English language, reserving the word “simios” for the apes, and correcting people who say “mono” when they see a chimp.

I tried hard to explain my position. It’s not a problem with taxonomy, it’s about distorting common language to follow the strict rules of taxonomy, thus causing confussion, absurdity, and noise in science communication. Sorry if I didn’t make it more clear.

Your English is excellent, better than that of many people for whom it is their mother tongue. The fact that there is no distinction in Spanish or French (or Italian) is interesting, since it appears that only in English does the distinction occur (a legacy of French and Germanic language routes perhaps).

The English language distinction is not a ubiquitous one – in common language ‘monkey’ is commonly used to refer to apes and it has been for a long time. It is only in the English scientific community that any distinction was made, based on paraphyletic convenience when discussing Old World and New World Monkeys.

This means that the argument for separating the apes from monkeys becomes void in light of systematic taxonomy. The logical options for dealing with this are as follows:

1) ‘monkey’ has no taxonomic equivalent and the term ‘monkey’ should not be used in science and therefore when used by the public it needs only to relate only to a common usage interpretation (which can be applied to the ‘apes’)

2) ‘monkey’ is given taxonomic equivalence with a clade, so it can be meaningfully used in science (in which case the clade needs to be identified).

If we go with option 1 there is no need to tell people to not call apes monkeys.

If we go with option 2 we need to identify a clade. That clade should sensibly include the New and Old World Monkeys, since they are both referred to in scientific literature as ‘monkeys’. The sensible choice for that clade would be the Simiiformes, although I would be happy to hear a logical argument for an alternative clade – but whatever it is it would necessarily include the apes given the the topography of primate phylogeny.

My point is that either ‘monkey’ is scientific or it is not. If it is not then apes can be called monkeys, if it is then they can be called monkeys. In neither circumstance is there a valid argument for apes to not be also be called monkeys. Note – I am not saying that apes SHOULD be called monkeys – I am saying that it is NOT WRONG to call apes monkeys…. a subtle, but important difference.

Pingback: Because we didn’t … « The Talented Chimp

Pingback: Friday mystery object #123 answer « Zygoma

Pingback: Humans Aren't Apes - Page 2 - Christian Forums

Pingback: Monkey ape | Autoserviciosm

Are you saying the queen of England is a monkey?

Aha! I must make it clear that I have been using the term monkey as a direct match for the term Simiiformes

Who are you to make that assumption? And right there your entire argument falls flat on its face.

There are NW monkeys, OW monkeys, and Apes. All are in the same infraorder “Simiiformes”. You have decided that this infraorder is where the term “monkey” belongs, I’m guessing because it includes both groups of monkeys. However, “Simiiformes” is not “monkey”. Its most direct equivalent would be “simian.” I don’t think anyone would object to saying that all monkeys AND apes are “simians.” You are substituting “monkey” for “simian” with no basis.

Monkey is not a translation of a scientific term (like simian = simiiformes). Therefore, the term “monkey” does not have a direct correlation to a clade, suborder, etc. Although if you’re going to be arbitrary about it, break it up at the family level. You could say the Cercopithecoidea are monkeys, the Hominoidea are apes. Then make up your own new term for the clade Platyrrhini. After all, the reason “monkeys” are in multiple clades is because it predates the scientific realization that the two groups of monkeys are not as closely related as once thought.

Who am I to make that assumption? Well, I am a beta taxonomist with an understanding of cladistics who is making an argument for that distinction. After all, names are not ‘true’ they are defined by usage and in terms of usage everything within the Simiiformes is commonly referred to as a monkey (if not by everyone).

I think I make the point more fully in the follow-up post: https://paolov.wordpress.com/2011/04/24/tired-of-monkeying-around/

I don’t know anyone who commonly refers to an ape as a monkey. It is much more common to refer to simians with tails as monkeys and simians without tails as apes. To make the point most bluntly there are New World Monkeys, Old World Monkeys, and Apes (and others that don’t enter into the discussion). Not, New World Monkeys, Old World Monkeys, and Ape Monkeys. Nobody I know ever refers to an Ape as a Monkey. Ever. People refer to Cercopithecoidea as monkeys. People refer to Platyrrhini as monkeys. No one refers to a Hominoidea as a monkey. At least no educated human I’ve ever met.

I believe I will start calling all felines grapefruits. If I can get a small sampling of fools to use this improper terminology, I guess we can tell people that a lion IS a grapefruit and somehow be justified.

It may be that no-one you know refers to apes as monkeys, but in my experience other people often do. US Law defines a monkey as a “non-human primate” (http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/7/2132) which includes all the apes except one. There is no word for ‘ape’ in languages other than English, everyone else refers to the apes using the same collective term as they use for monkeys. That makes ‘ape’ a bit of a niche term. Nonetheless, I clearly state that ‘apes’ remains a valid and useful term as it relates to a clade and I’m glad that you and your friends all use it – I do too.

‘Ape’ was a term that was commonly used to describe a tail-less monkey, but it followed the Linnean system of scientific classification. Therefore:

1) there is a precedent for scientific classification influencing common terminology

2) our system of classification has changed from exclusive typing to nested hierarchies

3) common terminology based on the old system should acknowledge this change.

I am not saying that apes should be called monkeys – since apes form a valid clade. What I am saying is that if a monkey clade is to make sense, it needs to include the apes. In which case, it is not valid to say that apes are not monkeys.

According to your selective law statute, for the purposes of that statute, it also says that most farm animals including horses and certain birds and mice are not animals. Although using your logic, you probably agree with that. A horse is not an animal because a US Law statute (which is defining animals for the purpose of a certain law case, not defining animals using any scientific or dictionary definition) says so.

The word in issue is monkey. This is an English term. Is it fair to drag other languages into it? But if you want to, I hit the dictionaries:

Spanish

monkey=mono

ape=simio

simian=simio

The particular dictionary does NOT translate ape to monkey. Instead it translates ape to simian. Therefore, according to this dictionary

1. monkeys not = apes

2. apes = simians

We know that all monkeys and apes ARE simians (you can not possibly dispute this). Therefore, since an ape is the same thing as a simian according to this Spanish dictionary, all monkeys are apes. All apes are not monkeys. This is actually the OPPOSITE of your argument.

In German, I get

Ape= Menschenaffe

Monkey=Affe

Simian=Affenart

So here, an ape is a “person monkey”. It has a translation different from just “monkey” though and it is not just the same thing as monkey.

You hit the nail on the head that “monkey” is not a valid clade and that it predates the current methods of classifications. Monkey is a blanket term that happens to describe multiple groups. A flying lemur is not a lemur. But it is called a lemur. Does this mean we find the closest common ancestor to both lemurs and flying lemurs and call them all lemurs? Hey look. All mammals are lemurs! That is what you seem to be doing to monkeys.

You say apes should not be called monkeys. But by putting apes in a larger group of monkeys, they CAN be called monkeys, which actually leads to more confusion since there are already several groups called monkeys. The larger group is called simians. Isn’t simians the larger group that monkeys and apes already belong to? Why make another group? Essentially saying a monkey is a type of monkey. Needlessly confusing, but I think that’s how the scientific mind works and the trend in classification. However, this classification is NOT there as much as you want it to be. Therefore, apes are not monkeys. Perhaps someday, but today is not the day.

I’m never going to get you to leave apes alone. And you’re never going to get me to call an ape a type of monkey. But when someone sees an ant and says “look at that wasp” everyone, you can be satisfied and the rest of the world will just shrug their shoulders I guess.

Wow – thanks for your comments on use of ape and monkey in other languages. Your points actually do a good job of reinforcing my point that language is mutable and definitions are required.

Interesting that you think that a name predating cladistic methods shouldn’t be altered to best fit phylogeny – in that case ‘ape’ also becomes invalid as there is a non-Hominoidea primate referred to in the Linnean system as an ape (the Barbary Ape, Macaca sylvanus).

You feel free to stick to your own definitions without updating them to match cladistic nomenclature – that’s just fine. I hope however that you will continue to refer to Barbary Macaques as Barbary Apes, as determined using the Linnean classification.

Changing the name of one small sub-species to fit phylogeny. Smart. Changing the broad all-encompassing common name of a suborder, etc… Not really feeling it.

Barbary Ape should be renamed (done). Definition of ape should not be changed. Flying Lemur should be renamed. Definition of lemur should not be changed.

Except of course nothing is changed by making the term monkey equivalent to Simiformes. The Hominoidea remain apes and the two clades of monkeys remain monkeys. The only difference is that the ape clade nestles in the monkey clade. This is the most logical way of incorporating the term monkey into a modern understanding of primate phylogeny.

I’m Spanish. In Spanish, “mono” and “simio” are originally synonyms. There was no difference between a “simio” and a “mono”. “Simio” was perhaps a more sophisticated term, but the animals were the same. We used to say “Los grandes monos” for the great apes or “los simios americanos” for the New World Monkeys. Years ago (I don’t know when) some Spanish scientists probably started to translate “ape” as “simio” and “monkey” as “mono” exclusively. They wanted to make the same distinction they found in English (but not in Italian, German, French…), so they broke the synonymy. This was, in my opinion, forced, artificial, and pedantic.

Spanish dictionaries are not very good at scientific terms, or when science jargon meanings are in conflict with common meanings of the same word. In some cases they are a disaster.

That’s a really interesting example of the usage in other languages, especially how there was an attempt to match the distinction found in English. I guess this was to match the Linnean taxonomy, which since been superseded anyway!

Thanks for your input!

Anyone know the origin of Ekembo – the new name for Proconsul heseloni? Someone told me it means “ape” in the local language (Swahili or a patois?) If it means “ape” as opposed to “monkey”, and is an old regional word, then the Kenyans also make a distinction between apes and monkeys… but I wait to be corrected.

just because you evolved from something doesn’t mean you are still considered ‘that thing’. If that’s true then I can call myself a fish….

Actually, you are considered ‘that thing’, although since we’re not talking about species, we’re talking about higher level groups, you’re considered ‘one of those things’. That’s why humans are classified as primates, mammals, amniotes, tetrapods, sarcopterygians, teleosts, osteichthyes, craniates, chordates, vertebrates, etc.

Fish is an ill-defined term, but since humans are classified as osteichthyes you can call yourself a fish without being wrong. You wouldn’t be giving away any useful information about the kind of fish you are, but you would not be wrong to call yourself a fish.

Humans evolved from an animal ‘closely related’ to modern apes, but not apes (hence we still have apes today). Apes did not evolve from monkeys. We are all primates though.

Nonsense. Apes DID evolve from monkeys, and humans DID evolve from primitive apes. You have no understanding of evolution whatsoever.

This is a very odd discussion. “Monkeys” are not a larger category than “apes” in anthropological classification. The correct term, if you wish to have one, would be that all monkeys, apes, and humans are members of the suborder Strepsirrhini, which in turn is divided in Platyrrhini (NWMs) and Catarrhini (OWMs). In no professional discipline dealing with primates are apes considered a type of monkey. That would be like saying that an apple is a type of banana.

In anthropological classification maybe, but that’s because anthropologists aren’t taxonomists. Read the second post on the topic for clarification: https://paolov.wordpress.com/2011/04/24/tired-of-monkeying-around/

It won’t let me edit my comment above — I meant to include apes and humans in the parentheses with OWMs.

We’re not monkeys, just apes. You might as well also say we’re reptiles, amphibians AND fish because we’re descended from those classes. The fact is, we are no longer any of those things, but we are still vertebrates.

Reptiles, amphibians and fish are not monophyletic groups, so they’re not valid terms in modern taxonomy and we are therefore not properly any of those things.

We are however members of the clade Osteichthyes and we don’t stop being members of that clade by being included in other nested clades – if that was the case then by being members of the clade Hominoidea then we would stop being part of the Primate, mammalian and vertebrate clades.

In a logically consistent taxonomy we can be attributed as members of any clade that we fall into, which includes the Simiiformes (which can be logically linked to the common name monkey).

If we’re vertebrates we’re also monkeys.

We aren’t reptiles. We didn’t come form reptiles. Nor were any of our ancestors reptiles. Reptiles, as a clade, is roughly equivalent to diapsids. We, as mammals, are synapsids.

BeatSeeker automatically checks out every feasible beat and also highlights the most commonly taking place patterns for whatever tool you’re working with.

Pingback: Nick Palmer, Writer

Ok, I realize this a VERY old post, but I just got into a DAYS long argument with two fools on youtube who, I think, have been INORDINATELY influenced by you (and never bothered to do even cursory research, instead choosing to take your word as absolute), so I HAVE to point this out.

Your entire argument is built on an error, and a GRAVE misunderstanding of evolution.

You say that apes descended from monkeys, and so on, but they DID NOT. The two share a COMMON ANCESTOR.

In your second diagram, you overlaid a red arrow pointing to the ancestors of all anthropoids, and labeled them “monkeys”. But that’s simply not true, as the tree ITSELF shows; those ancestors PREDATE Simiiformes ENTIRELY.

While I agree with you on the point about sharing a common ancestor, the node defines the clade and the simiformes node incorporates the platyrrhines, the catarrhines and the Hominidae plus Hylobatidae clade. The node that incorporates the catarrhines and Hominidae falls within the simiformes clade, which means that the common ancestor was a simiformes and therefore if the logic of assignment of the term ‘monkey’ to the simiformes is applied (as I argue here: https://paoloviscardi.com/2011/04/24/tired-of-monkeying-around/) then that shared common ancestor is a monkey.

Here is how it works. Apes and old world monkeys share a common ancestor 25 million years ago. Old world monkeys and new world monkeys share a common ancestor 40 million years ago. Since old world monkeys and new world monkeys share a common ancestor, that ancestor would, by definition, be a monkey. Since the common ancestor between apes and old world monkey is 25 million years ago, that means that the common ancestor of apes and old world monkeys was a monkey. And since you CANNOT grow out of your ancestry, that means that apes ARE in fact monkeys. You are nothing more than a modified variation of whatever it is your ancestor was.

Pingback: Orangutan watches a magic trick « Why Evolution Is True

I just want to add my five cents to this very old but nevertheless interesting topic. As it was mentioned before this is a problem exclusive to English language.

As a native Russian speaker I can provide you with ours point of view. In Russian we do not differentiate apes from monkeys that much. They are all обезьяны (“monkeys”), but if we want to specify that we are talking about apes we say человекообразные обезьяны (“human like monkeys”) this is also their scientific name. But it is more common to call a chimp or a gorilla just “monkey” in everyday speech.

People do commonly use the term “monkey” for both apes and monkeys, but many, if not most, those same people also generally call alligators lizards, frogs reptiles, bats rodents, and spiders insects. They are unaware there is a difference (or just don’t care), so no, I would not call a colloquialism a strong argument for assuming that “Simiiformes” and “monkey” are technically synonymous. While the aforementioned examples are clearly wrong, and apes I suppose are a subset of monkeys, those who understand the difference tend to use the proper term to be clear in exactly what they are referring to.

What a load of sophmore crap. There are humans and apes. Love all the the proper English though.

Humans are apes, dude.

I must say you have hi quality posts here. Your website should go viral.

You need initial boost only. How to get it?

Search for: Etorofer’s strategies

Pingback: When is a giant octopus not a giant octopus? | Fistful Of Cinctans

https://polldaddy.com/js/rating/rating.js

https://polldaddy.com/js/rating/rating.js

https://polldaddy.com/js/rating/rating.jsHi, sorry this seems like a rather old article but I am kinda confused on the subject and wanted to get some answers.

If we are apes because we came from apes, and we are monkeys because we came from monkeys, then how are we not fish, amphibians, or reptiles if our ancestors were some of these things? I mean, all life started out in the water and anything with a backbone has ancestry to fish, am I correct? I can understand to a certain extend how we may belong in clades from our ancestors since we inherit those traits. But can you be removed from a clade over time?

I’ve been trying to teach myself about taxonomy because the topic fascinates me but some things do kinda confuse me. Like the idea that we are apes just as birds are dinosaurs and snakes are lizards, but I am confused on how far back this goes in following our ancestry.

Thanks for any help!

We are part of every clade we are in, so effectively we are fish, although being pedantic ‘fish’ isn’t a clade, but Osteichthyes (bony fish) is, and we fall into that clade. Effectively this goes all the way back to our first ancestor. It is standard practice to refer to the name of the clade that is specific to the range of taxa you want to refer to. Therefore you wouldn’t refer to apes as monkeys if you wanted to just cover the ape clade. That doesn’t stop apes (including humans) from being monkeys however.

Not sure if that clarifies?

If we are in the clade “Osteichthyes” being bony fish, then shouldn’t that mean we would have the characteristic of that clade? (In this case: scales, fins, gills, laying eggs, cold blooded, etc) Otherwise, what’s the point of being in that clade? Organisms are put into clades based on their biology and characteristics, correct? I.E. Humans are monkeys because we’re warm blooded, posses hair, have aposable thumbs, four limbs, etc.

Also, I quickly looked up “human taxonomy” on google and couldn’t find that clade listed. Is there any site that is reliable and shows all the clades including this one? Mainly for future reference.

Nope, clades are defined by shared common ancestry (nodes on the stem of a cladogram), not by the character states of the crown taxa. Using shared common characters is the traditional approach to taxonomy and because evolution involves traits changing (being lost between closely related taxa or even converging in distantly related taxa), it’s not a very reliable system. That’s part of why cladistics was adopted in the first place.

But then clades are meaningless. We’re mammals because we share the characteristics that defines mammals. If our descendants eventually lose those traits and become something else then what’s the point to calling them mammals?

Actually, clades are far more meaningful than artificial groupings based on similarity, because the tell us the evolutionary relationships between taxa. These provide far more valuable information than arbitrary names applied for convenience, since they reflect something real.

In answer to your question, the point to calling them mammals is to recognise that they have their evolutionary roots within the mammals, allowing a better understanding of what changes would have needed to occur for them to look so different to their other mammal relatives.

Just think of whales.

Pingback: Is the vampire squid an octopus or a squid? | Fistful Of Cinctans

“After all, you don’t refer to your pet cat as a pet carnivore…”

Says you.

Joe Rogan just mentioned this article while talking to William Von Hippel (JRE #1201).

Thanks for letting me know!

I think, to be as unbiased and fair as possible and also not as smart as the rest of the people commenting here, that the problem comes in with calling apes monkeys less with you educated knowledgeable folks,and more with Joe public. As someone who has worked with great apes and new world monkeys both( and really enjoys the new world monkeys quite a bit) I feel like my personal issue with seeing bonobos or chimps in TV shows referred to as monkeys is more about connotation than denotation. The official meaning isn’t the concern. The concern is that when people use ‘monkey’, the level of respect goes way down.

I’m a big primate fan. I love me my capuchins. I am into some new world primates, man. I am a fan of macaques. But after working with a variety, I can honestly say that a great ape feels on the mental and emotional level of a human being. They’re people, as far as I’m concerned, as far as it matters in my world. And to call them a monkey puts people who are not in a primate (or animal, really) related field in the mindset of an animal who they would not respect at their own level, and even if a chimpanzee is not a person, they have proven that they should be treated, emotionally and intellectually, on the same level.

They aren’t alone in this, among nonhumans.They also aren’t humans, yes. But in the way of the general human population, you have to tailor your message to the people, and people won’t respect someone with a depth similar to a human unless told to.

So my problem with calling apes monkeys isn’t about technicalities, or about feeling superior. It’s about adjusting my own expectations to general humanity and then supporting the language and education that will lead to nonhuman primates getting the understanding and respect from the greatest number of people.

So yes, maybe calling apes monkeys isn’t wrong. But maybe you should think a bit more about the immediate good of such a declaration would do for nonhumans than how right smartass humans would be, because one of us is pretty much a plague at this point and the other is on the verge of disappearing and could really do with some assistance, grammar and scientific clarification be damned.

Don’t mean to be aggressive or mean but like.

Dude. Help conservation out a little maybe. You care enough to know, so I’m hoping you care enough to do some actual good.

J, I agree.

To those that insist on calling apes monkeys (yes, scientifically they are…so what…), for the best interest in the general public helping our endangered friends…just…please…no! Don’t call apes monkeys.

Informal animal education/educators work very hard to educate children and the public on the differences between primates. It is difficult enough to get children — let alone adults — to care about the diversity and extinction of certain animals in our world without the concern that the internet now says that all apes really are monkeys.

Please help conservation by simplifying instead of making it more confusing to the masses? For each person out there that is educated that an ape is an ape, a prosimian is a prosimian and a monkey is a monkey, that person is more likely to be a primates friend.

OMG! Shakespear said it best. ‘Much ado about nothing’. But I must admit this did take my mind off the COVID Virus. I can just see Ross Geller giving this disertation to all the others drifting off to sleep on the couch in Central Perk!🤣😂😆

Pingback: On All Levels Except Taxonomical, I Am a Monkey. – Texas EEB Club